Becoming a nurse was the obvious choice for Oliver Isleta.

The economy in the Philippines, his home country, was sluggish, and he wanted to make a better living abroad…. So after studying nursing in the city of Davao, he emigrated to the US in 2006 to take his board exams.

He lived first in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in a dormitory with other Filipino nurses, before moving to Fresno, into the granny flat behind his sister’s house. Twelve-hour night shifts at Community Regional Medical Center left Isleta so tired he could barely walk on days off….

His salary flowed back overseas to relatives in Davao, where his wife and son Matthew counted down his once-a-year visits—timed to coincide with Matthew’s April birthday—and hoped to ... join him in California.

On September 1, [2020,] that future disappeared, when Isleta died from COVID-19 complications at Community Regional.1

Isleta’s story is not unique. Filipino nurses specifically, and people of color generally, have been disproportionately put in harm’s way throughout the pandemic—but also long before.

This article is about the weaknesses that structural racism creates in our nation, particularly in our approaches to healthcare and public health. If you’re looking for recommendations for how to begin solving our longstanding challenges, click here to jump to the section below. If you’re interested in understanding the racial nature of our economy and of our disinvestment in public goods (including our political struggle to provide healthcare coverage for all), read on. The authors explore our society’s dramatically different reactions to the crack (Black) versus opioid (white) epidemics and our colonialist journey to relying on nurses like Isleta. Along the way, they explain that both are rooted in racial capitalism, which systematically undervalues the labor, health, and lives of people of color, and they point to a path forward so that the cascading crises of the COVID-19 pandemic can be avoided in the future.

–EDITORS

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disastrous impact on countries around the globe, and our collective responses have demonstrated—in glaring detail—the inequities embedded in our systems. Early in the pandemic, due to the country’s slow, disjointed response, the United States quickly became the global epicenter of COVID-19. And yet what that meant for one’s daily life varied enormously. From the teleworking professionals having their groceries delivered to the warehouse workers struggling to fulfill orders to the nurses caring for patients dying in hallways, the impact of this pandemic has been drastically different for each person depending on their place in our society. Two clear lessons quickly emerged: First, that COVID-19 cases and deaths disproportionately wreaked havoc in marginalized racial and ethnic groups. Second, that these inequities were, in large part, consequences of the structural racism embedded within the social fabric of the United States.

Despite progress made during the civil rights movements of the 20th century,1 people of color remain disproportionately marginalized, overrepresented in segregated communities with crumbling infrastructure and severely limited opportunities. Historical and persistent disinvestment by public and private entities is so extensive that during the pandemic, basic public health recommendations of hand hygiene and self-quarantine have been challenging, if not impossible, to follow.2 Substandard housing, crowded conditions,* and limited and/or unsafe water have hampered our collective ability to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Many of our most exposed and least visible “essential workers” are from these racially and economically segregated neighborhoods. Like most Americans, especially in states that rejected Medicaid expansion, these workers depend on anemic employer-sponsored health insurance3 or must cut back on other basic needs to buy Affordable Care Act plans in order to get any level of routine care. And even if they have coverage, it is difficult to use because too often they do not have paid sick leave.4 These same workers are far from grocery stores with affordable, fresh vegetables and close to polluters like bus depots and industrial zones; they also have higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, and asthma and are more likely to have healthcare services that are under-resourced and understaffed.5

These structural inequities do more than make us vulnerable as isolated communities—they make us vulnerable as a nation, reducing our ability to weather and recover from disasters. Our national housing crisis and food insecurity make us vulnerable to the next pandemic. Precarious, inequitable working conditions and lack of paid sick leave make us vulnerable to the next pandemic. Our dependence on prisons and jails to deal with social and public health issues makes us vulnerable to the next pandemic. Our poorly coordinated, profit-focused health systems make us vulnerable to the next pandemic. Our immigration policies, systematic neglect of the elderly, and lack of early childcare and education make us vulnerable to the next pandemic. Deep structural inequities make us more vulnerable to the next pandemic.

It has taken the COVID-19 pandemic for some to see the inequities at work in our everyday lives, but this recognition now allows us the opportunity to course-correct. It’s time to revive the idea of public goods and rekindle our commitment to our collective—not just our individual—well-being. Never in recent history has the need to dismantle the structural and institutional barriers to health equity been clearer.

Why Race Matters, Even When It Seems Irrelevant

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the many ways that health conditions do not operate on a level playing field. Virtually every health and social outcome is patterned by race and ethnicity. But why? As we will explain, at the heart of the many interwoven causes is the difficulty of dismantling racism within our society. Racism goes well beyond interpersonal discrimination; it “has a structural basis and is embedded in long-standing social policy.”6 When we describe racism as structural, we are referring to “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice.”7 These systems prop up existing prejudices, values, and inequities in the distribution of resources. Structural racism itself can be hard to see, but its outcomes—like disparities in health insurance and access to preventive care—are not.

Many of us in the United States would like to put enslavement, Jim Crow, segregation, and racism behind us. Many people think that if we stopped talking about this history and approached each individual on their own merits, racial disparities would go away. We wish that were true. But our current conditions are the product of hundreds of years of cultural beliefs and policy decisions, and it will take a great deal of collective, concerted effort to make the United States the level playing field we aspire to be. Although we have made progress in recent decades, structural racism remains embedded within the social, economic, and political fabric of our country; it is most prominent in our low level of investment in public goods, like infrastructure, public health, and the social safety net (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security, and affordable higher education).

Austerity regarding public goods began soon after the civil rights movement started opening our public goods to African Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. It has not only led to the country’s overall structural vulnerability to major public health threats, like the COVID-19 pandemic—it has also been at the root of the struggles of the white working class.8 The commitment to privatization and deregulation has been a serious problem since it began gaining momentum in the 1980s. Because of the legacies of enslavement and discriminatory immigration policies and then segregation of housing, employment, and services, people of color largely filled the lowest levels of our economic structure, and they felt the initial impact of these policies most strongly. In contrast, white working-class communities were mostly protected from feeling the impacts so long as the private sector was booming in white working-class communities. It took the Great Recession of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic to bring the full impacts of our highly unjust policies—in which the rich amass unimaginable wealth while governments are unable to pay for basic public goods like healthcare for all—to a broader swath of the middle and working classes.

Still, understanding the racial nature of seemingly nonracial policies can be very difficult. Here, we offer two case studies to examine what might appear to be race-neutral initiatives: our divergent reactions to the crack and opioid epidemics and our reliance on Filipino nurses. Along the way, we briefly explore the fading American dream and why America’s version of free market capitalism is really racial capitalism.

Racialized Drug Policies

Modern drug policy goes back at least as far as the 1960s, when recreational drug use rose alongside countercultural “turn on, tune in, drop out” lifestyles and reports that 15 percent of American soldiers in Vietnam were addicted to heroin caused panic at home.9 However, by the time President Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs in 1971, the dominant narrative in our society portrayed drug use as a criminal pathology inherent to urban, low-income Black and Latinx communities, one that could only be eradicated with aggressive policing and harsh prison sentences. That narrative is well known. But not so well known is the political motivation for it: In a 1994 interview, John Ehrlichman, who had served as a domestic policy adviser to Nixon, said,

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and [B]lack people…. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or [B]lack, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and [B]lacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.10

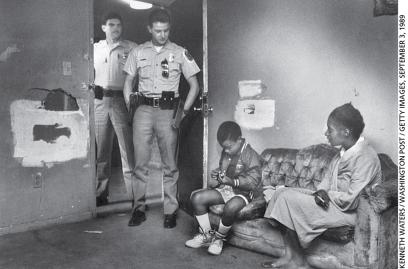

Given how successfully this narrative took root in the 1970s, it’s no surprise that President Ronald Reagan doubled down on it in the 1980s as crack cocaine made its way onto urban streets. While crack was not relegated solely to urban Black and Latinx communities, the narrative around the crack epidemic was one of Black and Latinx men as gang members, fiends, and predators who deserved to be punished, and of Black and Latinx mothers as deviants whose pathological addictions condemned their children (“crack babies”) to a life of permanent disadvantage. This new front in the war on drugs drove mass incarceration; it was concentrated in segregated Black and, to a lesser extent, Latinx communities.11

And yet, at the same time, Wall Street professionals and Hollywood stars were infamous for using powder cocaine—but rarely facing any consequences.12 Biologically, there’s little difference between cocaine and crack, which makes the racial nature of the so-called war on drugs especially clear. Under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the distribution of just 5 grams of crack carried a minimum federal prison sentence of five years, compared with 500 grams of powder cocaine for the same sentence.†

The only real difference between crack and powder cocaine was that crack was so much cheaper and more accessible to poor Americans, especially Black Americans in segregated neighborhoods suffering from decades of disinvestment. Still, people of color were targeted further through discriminatory policing and prosecution. In 2003—at the height of mass incarceration—more than 66 percent of crack users were white or Hispanic/Latinx, but they made up only 18 percent of defendants sentenced under harsh federal sentencing law, while Black people made up a whopping 81 percent.15‡ The impacts of this disproportionate enforcement of inequitable laws have not been limited to those who are locked up; families and communities have been torn apart—just as Nixon intended.

Now consider the very different narrative that has been constructed for the opioid crisis: media portrayals focus on opioid users as mostly rural and suburban white Americans who are victims of profit-seeking, predatory pharmaceutical companies.17 Politicians demand treatments and lawsuits against the pharmaceutical companies, not harsh sentences for the opioid users. In a congressional hearing in July 2017, Brian Moran, Virginia’s secretary of public safety and homeland security, said, “We cannot arrest our way out of the heroin and opioid addiction crisis.”18

Now, as the impacts of our decades of disinvestment in public goods are being felt by white middle- and working-class Americans, we have a narrative focused on “deaths of despair”—gun-related suicides, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths.19 These deaths are linked rhetorically to places where manufacturing and other blue-collar jobs have disappeared, and where the communities that formerly supported these industries are experiencing high associated social costs.

In conversations about opioid addiction and deaths of despair, a big part of the explanation is the loss of purposeful employment and of hope more generally. Of course, these are the same mechanisms that were at play with the crack epidemic in segregated, disinvested neighborhoods. Addiction is a behavioral health issue that rears its head wherever there is a loss of purpose and hope, regardless of race or ethnicity. Two decades before the conceptualization of deaths of despair, renowned Black sociologist William Julius Wilson described a similar connection between the decline in work opportunities in urban Black communities and the rise of health and social issues.20 Yet economic shifts by themselves need not lead to despair; it’s the combination of economic change and the lack of public goods—lack of strong job-retraining programs and sufficient assistance to avoid family poverty while engaged in retraining, for example—that causes a person to lose hope. This loss of hope and purpose is a collective American problem—a symptom of the fading American dream.

The promise of the American dream is that with enough hard work and determination, anyone can have a better life. The meaning of “a better life” varies, but one way to measure it is by comparing earnings across generations. While 92 percent of children born in 1940 went on to earn more than their parents did by the age of 30, that was the case for only half of children born in 1984.21 What happened? Rising inequality. There’s been plenty of economic growth, but it has not been distributed fairly (for details, see the article “Moral Policy = Good Economics”). The fruits of our labor have primarily accrued to those at the very top, especially in recent years.

Not surprisingly, this loss of upward socioeconomic mobility is also patterned by race and ethnicity. Data collected between 1989 and 2015 show that Black Americans and Native Americans have experienced lower rates of upward mobility and higher rates of downward mobility than white Americans.22 These disparities feed intergenerational gaps in resources. According to data gathered between 2017 and 2019, for every dollar that white workers earned, Black workers earned 76 cents, Latinx workers earned 73 cents, and Native American/American Indian workers earned 77 cents23—not much better than the racial income gaps in 1978.24

Racial disparities in wealth (e.g., assets like savings accounts and home equity) are larger than those for income and education, and wealth makes an incremental contribution to health and health disparities over and above income and education.25 For every dollar of wealth white households have, Black households have 10 cents and Latinx households 12 cents.26 Because of our minimal public investments and weak social safety nets, Americans rely mainly on private, individual safety nets when emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic arise; so the unequal distribution of private household reserves across generations further polarizes the experiences of the haves and the have-nots.

Together, what these results tell us is that we need to collectively reduce income inequality across neighborhood, class, and racial lines, while specifically emphasizing the upward social mobility of the people who have been systematically excluded from opportunities to rise.

Racial Capitalism

In order to address income inequality and social mobility across our population, we must confront the centrality of race in our social and labor hierarchies. This requires us to reconsider how we think about our economic system. Proponents of “free market” capitalism, a largely self-regulated economy that maximizes profit and minimizes government oversight and regulation, claim that it offers equal opportunities to everyone because free markets are rational, neutral, and unbiased.

However, we need to consider the context in which the US free market economy formed. Slavery was the first big industry in the United States, and the very bodies of the enslaved were the country’s largest financial asset.27 But even as the humanity of enslaved people has slowly come to be recognized, the American brand of capitalism has continued to make race a key factor in the value of labor. In effect, we practice racial capitalism, in which low-wage and high-risk work is concentrated among historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups.

The concept of racial capitalism recognizes the links between capitalism and colonialism. The development of race as an organizing principle within Europe several hundred years ago was largely a colonial process involving the invasion and settlement of lands possessed by Indigenous American, African, and Asian peoples, expropriation of natural resources, and establishment of a racial hierarchy that placed white Europeans at the top. But it didn’t stop there. The history of anti-Mexican and anti–Central American immigrant sentiment is better known, but the waves of European immigrants to the newly formed United States in the 19th century were also subject to the racialized social, economic, and political systems established by European settlers. Irish, German, Italian, and Eastern European people, especially Catholics and Jews, were discriminated against as not truly white and struggled to find jobs and places to live.28 The concept of racial capitalism helps frame everything from European explorers’ treatment of Native Americans to slavery to anti-immigrant sentiment to the continued devaluing of people of color. One stark example within healthcare is our nation’s dependence on nurses from the Philippines.

Racialized Nursing Policies

Filipino Americans play an outsized role in the US nursing workforce—including in COVID-19 cases and deaths. They are 1.1 percent of the US population but account for 4 percent of the nation’s nursing workforce and about 25 percent of all COVID-related deaths among nurses. In California alone, where about 20 percent of nurses identify as Filipino (compared with 3 percent of the California population), they accounted for 23 of the 38 COVID-19 deaths in the profession as of February 11, 2021. This is because they are more likely to be assigned to critical care settings with highly infectious patients (intensive care units, emergency departments, nursing home bedsides), thus experiencing disproportionately prolonged exposure, in dangerous working conditions and without proper protection.29 They are the frontline of the frontline healthcare workers.

Why? There is a century-long legacy of colonialism and discrimination. In 1898, after a US Navy ship sank in Havana Harbor, the United States entered into the ongoing Cuban War of Independence against Spain. Hostilities quickly extended to other arenas of war, including the Philippines and other Spanish colonies in the Pacific, launching the Spanish-American War. This three-month war led to US control of Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and, temporarily, Cuba. At the end of the war, President William McKinley issued a proclamation:

We come not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights.… Finally, it should be the earnest wish and paramount aim of the military administration to win the confidence, respect, and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines … by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule.30

This notion of “benevolent assimilation” was an extension of the US ideology of manifest destiny and the idea of the “White Man’s Burden” popularized by British writer Rudyard Kipling: white colonizers had a duty to rescue Indigenous people from their supposedly primitive and uncivilized ways of life.31

Under US colonization of the Philippines, Filipino nurses were trained by Americans in Americanized nursing schools (and in English) so they could work in the United States. Adding to the handful of existing hospitals established by the Spanish regime, about 20 American hospitals and schools of nursing were established between 1906 and 1947, plus three colleges of nursing between 1946 and 1948. That’s when the export of nurses began, as the United States had a post–World War II healthcare staff shortage to address and had launched an Exchange Visitor Program that made hiring foreign labor inexpensive and easy.

By the 1960s, nurses were migrating to the United States by the thousands because of an abundance of jobs created by the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid. In addition, the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 allowed a preferential approach to immigration; certain categories of immigrants, such as highly educated Asian scientists, engineers, and doctors, as well as Filipino nurses, were permitted to come to the United States in greater numbers. As of 2019, 1 out of 20 registered nurses in the United States was trained in the Philippines.32

Since the 1960s, 150,000 Filipino nurses have migrated to the United States for healthcare jobs. Like many other immigrant laborers in US history, they have often found themselves in demanding and dangerous work environments. From the 1980s to today, Filipino nurses have disproportionately cared for patients during America’s HIV/AIDS, SARS, Ebola, and COVID-19 crises. Even when we are not facing a healthcare crisis, Filipino nurses suffer from exploitation, such as being assigned the less desirable shifts and the more precarious settings.33

To better understand the plight of today’s Filipino nurses, we need additional historical context. The first group of immigrants to be barred from the United States was Asian. The 1875 Page Act was the first federal immigration law; it prohibited the entry of supposedly undesirable immigrants, including any individual from “China, Japan, or any Oriental country” who was coming to America as a contract laborer. In particular, the Page Act targeted Chinese laborers, who were depicted as filthy and unsanitary, a physical as well as a religious and moral threat to the Christian United States. Chinese women were perceived as a particular type of threat: they were stereotyped as prostitutes who spread sexually transmitted diseases.34 Later laws continued in this vein, including the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 and the Asian Exclusion Act in 1924.

And yet, just four decades later, sociologist William Pettersen coined the term “model minority” in an article for the New York Times Magazine.35 He attributed the apparent success of Japanese Americans, only 20 years after their incarceration in internment camps during World War II, to their cultural values, strong work ethic, family structure, and genetics. Numerous newspaper and magazine articles subsequently appeared describing the “successes” of various Asian American groups.

Pettersen’s article can be considered in direct contrast to the 1965 Moynihan Report, which blamed Black culture and family structure for Black communities’ socioeconomic problems.36 The “model minority” analysis pitted Japanese Americans—and, later, all Asian Americans—against so-called problem minorities, putting wedges between Asian and Black communities37 and masking the wide disparities among and within diverse Asian American and Pacific Islander groups in terms of income, employment, education, health, housing, and immigrant experience.38 Perhaps most importantly, in suggesting inherent reasons that “model minorities” succeeded where “problem minorities” did not, it offered a distraction from examining the role of structural racism in understanding disparities between white and Black Americans.

In the last couple of decades, our postindustrial, service-based economy—with a minimum wage that’s far too low to live on—has created marginal and inequitable opportunities for new immigrants and heightened economic hardships for native-born people of color. These conditions have been presented as new fault lines in race relations, beyond the civil rights era paradigm of white and Black relations. But such divisions among people of color only benefit the dominant group. While it is important to recognize the ways Asian Americans have benefited from anti-Black racism in the United States, for example, it is also important to recognize that the struggles for equity of Black Americans, Asian Americans, and other marginalized groups are, in effect, the same struggle against white supremacy. Conflict among racial and ethnic groups is a product of structural racism—and both can be dismantled if all of those who cherish equity stand together.§

We must face the reality that, by disinvesting in public goods, we have been smothering the American dream for decades. Attacks on “big government” as an excuse to cut public investments have largely translated into big corporations consolidating profit and political influence to the detriment of the American people. We can no longer reasonably ignore the realities of racial capitalism, structural racism, and the dangers of our divided, inequitable society.

We can see how our macroeconomic policy choices negatively impact our health and well-being simply by looking at life expectancy in the United States over the last 70 years. While life expectancy has increased since the 1950s, the rate of increase slowed beginning in the early 1980s, diverging from the upward trajectory of other wealthy nations. It actually decreased from 2014 to 2018 among all racial and ethnic groups, rising slightly through 2019 before dropping precipitously during the pandemic.39 The decrease in life expectancy between 2018 and 2020 was 1.9 years, 8.5 times the average decrease in peer countries. The numbers are even starker for Hispanic populations and non-Hispanic Black populations: compared with peer countries, life expectancy decreased by 18 and 15 times the average, respectively.40

This decrease in life expectancy is shocking, but it’s also highly predictable. Our social contract has been deteriorating for decades and needs renegotiating.

Public Health as a Public Good: Investing In Our Future

In order to act on the key lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, we must reimagine our economy, ensuring human rights and human dignity by valuing our health and well-being as a shared common good.

We find hope for this reimagining in the concept of adaptive governance grounded in grassroots civil society and public systems offered by 2009 Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom.41 Ostrom’s early work emphasized the role of public choice in decisions influencing the production of public goods and services. Caring for the commons had to be organized from the ground up, shaped to cultural norms and based on a foundation of trust. Her recent work has documented how communities around the world—including in Guatemala, Kenya, Los Angeles, Nepal, and Turkey—have devised ways to govern public goods to ensure their survival and the survival of future generations. Essentially, success depends on a well-supported, active civil society engaging with the government. Robust community organizations strengthen local decision-making, promote mutual accountability, and galvanize joint progress, which engenders more support for shared public goods and long-term sustainability.

Local Investments

In the United States, we should invest in our local health departments as our boots on the ground, building a public health and social service infrastructure that employs community health workers who are paid a living wage and afforded occupational protections. We emphasize investment in local health departments because they are closest to the need, hold stronger relationships with community organizations, and are more likely to be held accountable for action and inaction.**

- In general, state health departments that are centralized—that is, whose decision-making is closely controlled and managed by governors at the state level—are slower and less effective at launching preventive measures, expediting hiring and purchasing, and receiving additional funds from the federal government during a public health emergency response.42

- More hierarchical state health departments are less likely to be prepared, have a comprehensive pandemic plan, or rapidly deploy resources during a pandemic.43

- Delayed public health responses may disproportionately impact historically marginalized racial and ethnic communities with more residential and occupational exposure to COVID-19 (and other diseases).

Federal Investments

Although we believe local investments are essential for improving public health, our local initiatives are far more likely to succeed if they rest on a strong foundation of federal investments.

Our federal investments should begin with a well-resourced Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) whose mission, mandate, and leadership extend beyond specific presidential administrations.

- Between 2008 and 2014, public health expenditures per capita decreased by 9.3 percent, and federal budget cuts compromised critical resources, including the pandemic unit of the US National Security Council in China, the CDC’s emergency preparedness budget, and states’ spending on public health programs.44

- The sidelining of the CDC in the COVID-19 pandemic response and the politicization of the role of its director has largely marred the credibility and reputation of the agency and reduced public trust in it as a public good.45

- The CDC’s credibility and reputation must be rebuilt bit by bit, including by increasing transparency with the public, building stronger relationships with state and local health departments, and resisting the push to increase the number of political appointees and other lobbying forces in the agency.46

We should invest in Medicaid and healthcare for all. And we should invest in the Indian Health Service, not through annual congressional appropriations, but as an entitlement program for this land’s first peoples.††

- There are still more than 30 million US residents without health insurance; these are disproportionately people who are Black or Latinx, are young, have low incomes, and/or live in states that have not expanded Medicaid.47

- Access to healthcare is a strong predictor of health; poor access to routine healthcare is associated with poorly controlled chronic disease.48 (Importantly, a large percentage of COVID-19 deaths in the United States have occurred among patients suffering from chronic conditions, like hypertension, obesity, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.49)

- Potential healthcare costs prevent the timely testing, contact tracing, and treatment needed to curb the spread of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.50

We must invest in workers’ rights by ensuring safe work environments, mobilizing an independent Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and supporting broadscale labor organizing efforts.

- Union organizing improves levels of compensation (in wages and fringe benefits) as well as quality of life for both unionized and nonunionized workers.51

- The federal government through OSHA should routinely mandate emergency safety measures for employees during public health emergencies, such that workers are not sacrificing their own and their families’ well-being to maintain their employment.52

- Labor organizing has shown itself to be an opportunity for racial and ethnic solidarity. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. advocated for unionism in human rights, environmental justice, and economic justice, not only as political participation but also as our moral obligation for the next generation.53 A new study finds that white union members are less likely to have racist attitudes than white workers in similar industries who are not in a union. Additionally, becoming a union member, or even being a former union member, reduces white workers’ racial resentment. Such lessening of racial resentment even translates to increased support for policies like affirmative action.54

- For our democracy to thrive and to rebuild the public good, we need to invest in and foster an active, unfettered, multiracial, and multiethnic civil society. The 21st century Poor People’s Campaign led by Rev. Dr. William Barber II and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis lays out a comprehensive social movement whose moral policy agenda hinges on the right to democracy and equal protection under the law, the right to welfare and an adequate standard of living, the right to work with dignity, the right to health and a healthy environment, and the reprioritization of our resources toward these goals.55 The movement has launched direct actions across the nation supporting a $15 minimum wage, equitable voters’ rights, and government accountability across administrations and parties.

Given the structural inequities at play, we must address the root causes of health inequities by transforming the environments and policies that produce inequities. One critical place to start is investing in high-quality early childcare and education for working families.

- Childcare is beyond a family issue—it is part of the business infrastructure enabling parents (especially mothers) to work and is a major tool to level the playing field across classes and genders.56

- The CARES Act provided block grants to subsidize childcare; it also allowed for 12 weeks of paid sick leave for employees without access to childcare or school for their children. We now need to earmark funds for essential workers and independent contractors57 and create a sustainable emergency childcare system that can be deployed during subsequent public health crises.

We should invest in our public infrastructure to produce quality public schools, social services, and behavioral health rather than investing in the inequitable, punishment-focused prison industry.

- The environments of jails and prisons amplify health risks, including and beyond COVID-19.

- We can address the collective health vulnerability associated with mass incarceration by decreasing the number of people who are sentenced to correctional supervision and increasing investments in addressing the root causes of crime, namely by expanding education and economic opportunities equitably.58

Ties That Bind Us

While holding onto the virtues of liberal thought—respect for human rights, freedom of thought, freedom of assembly—we believe the United States would be stronger and better prepared for the next pandemic if we coalesced around a more collectivist approach to public policy.

We Americans have much in common, most importantly innovation, resourcefulness, and a desire to make our communities better. If we want the United States to become the equitable and just country we believe it can be, we must recognize the linked fates of our diverse communities and grow personal relationships and trust among community leaders and stakeholders from all backgrounds and walks of life. We need to continue promoting a culture of engagement and inclusion and recognize the need for cultural humility and an understanding of our unique history and how it has brought us to our present moment. Furthermore, we must demand that our economic system shift toward greater investments in shared public goods and in better wages and benefits for our least advantaged workers.

Throughout American history, when we have not planned with equity in mind, we have defaulted to inequity. It is up to us, individually and collectively, to recognize the ongoing impacts of structural racism and become a diverse, united group of anti-racist investors in American prosperity. We need to—must—do better, because our future depends on it.

Zinzi D. Bailey, ScD, is a social epidemiologist, faculty member at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and associate director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Interdisciplinary Research Leaders. J. Robin Moon, DPH, MPH, MIA, is a social epidemiologist and faculty member at the City University of New York’s Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, School of Medicine, and Institute for Health Equity.

*For decades, government policies forced African Americans into substandard, crowded housing (while helping white Americans move into new, affordable homes). To learn about these policies and their ongoing impact, see “Suppressed History: The Intentional Segregation of America’s Cities” in the Spring 2021 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

† In 2010, the Fair Sentencing Act reduced but did not eliminate the discrepancy between sentencing for crack and powder cocaine; under this act, the distribution of 28 grams of crack triggers the same mandatory five-year federal prison sentence as for 500 grams of powder cocaine.13 As of September 2021, legislation to eliminate the disparity was being considered.14 (return to article)

‡ By 2020, the numbers hadn’t changed much: white and Hispanic/Latinx people constituted 22.7 percent of defendants for crack distribution, while Black people constituted 76.8 percent.16 (return to article)

§ Today, the role of Asian Americans as a racial middle is critical. If Asian Americans buy into and strive to attain the privilege of white Americans, they will help perpetuate our racial economic system. Conversely, Asian Americans can help increase equity if they refuse to buy into racial hierarchy and strive to dismantle white privilege. (return to article)

** We do not focus on action on the state level due to high between-state and within-state variability and state governments’ tendency to focus on politics instead of communities’ strengths and needs. (return to article)

†† To read about how contact with US settlers has affected Native American health, read “Traditional Food Knowledge Among Native Americans” in the Fall 2020 issue of AFT Health Care. (return to article)

Editors’ Endnote

1. F. Kelliher, “California’s Filipino American Nurses Are Dying from COVID-19 at Alarming Rates,” Mercury News, October 4, 2020.

Article Endnotes

1. Lumen, “Expanding the Civil Rights Movement,” Boundless US History, courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/expanding-the-civil-rights-movement; and V. Gosse, “Red, Brown, and Yellow Power in ‘Occupied America,’” in Rethinking the New Left (New York: Palgrave, Macmillan, 2005), 131–51.

2. Z. Bailey and J. Moon, “Racism and the Political Economy of COVID-19: Will We Continue to Resurrect the Past?,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 45, no. 6 (2020): 937–50.

3. A. Tomer and J. Kane, “How to Protect Essential Workers During COVID-19,” Brookings (blog), March 31, 2020.

4. C. Miller, S. Kliff, and M. Sanger-Katz, “Avoiding Coronavirus May Be a Luxury Some Workers Can’t Afford,” New York Times, March 1, 2020.

5. G. Ogedegbe et al., “Assessment of Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hospitalization and Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in New York City,” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 12 (2020): e2026881.

6. Z. Bailey, J. Feldman, and M. Basset, “How Structural Racism Works—Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities,” New England Journal of Medicine 384, no. 8 (2021): 768–73.

7. Z. Bailey et al., “Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions,” The Lancet 389, no. 10077 (2017): 1453–63.

8. H. McGhee, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together (New York: One World, 2021).

9. A. Janos, “G.I.s’ Drug Use in Vietnam Soared—With Their Commanders’ Help,” History.com, August 29, 2018.

10. D. Baum, “Legalize It All: How to Win the War on Drugs,” Harper’s Magazine, April 2016.

11. V. Newkirk, “What the ‘Crack Baby’ Panic Reveals About the Opioid Epidemic,” The Atlantic, July 16, 2017; and J. Netherland and H. Hansen, “The War on Drugs That Wasn’t: Wasted Whiteness, ‘Dirty Doctors,’ and Race in Media Coverage of Prescription Opioid Misuse,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 40, no. 4 (2016): 664–86.

12. B. Weiser, “Wall St.: High Pressure, High Powered, Often Just High,” Washington Post, May 13, 1994; and B. Hudson, “Cocaine in 1980s America: Fine for the Wealthy & Well-Educated; Bad for the Poor,“ Points: Short & Insightful Writing About a Long & Complex History (blog), February 18, 2021.

13. G. Grindler, “Memorandum for All Federal Prosecutors: The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010,” US Department of Justice, August 5, 2010, justice.gov/sites/default/files/oip/legacy/2014/07/23/fair-sentencing-act-memo.pdf.

14. Sentencing Project, “Race & Justice News: Eliminating Crack/Cocaine Sentencing Disparity,” Race & Justice News, July 27, 2021.

15. D. Vagins and J. McCurdy, Cracks in the System: Twenty Years of the Unjust Federal Crack Cocaine Law (Washington, DC, and New York: American Civil Liberties Union, October 2006).

16. US Sentencing Commission, “Table D-2: Race of Drug Trafficking Offenders, Fiscal Year 2020,” 2020 Datafile, USSCFY20, ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/annual-reports-and-sourcebooks/2020/TableD2.pdf.

17. Newkirk, “What the ‘Crack Baby’ Panic Reveals.”

18. US House of Representatives Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, “Combating the Opioid Crisis: Battles in the States,” US Government Publishing Office, July 12, 2017, govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg26839/html/CHRG-115hhrg26839.htm.

19. A. Case and A. Deaton, “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife Among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 49 (2015): 15078–83.

20. W. Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Vintage Books, 1996).

21. R. Chetty et al., “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940,” Science 356, no. 6336 (2017): 398–406.

22. R. Chetty et al., “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135, no. 2 (2019): 711–83.

23. US Department of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, “Earnings Disparities by Race and Ethnicity: Earnings Disparities by State, National Totals,” dol.gov/agencies/ofccp/about/data/earnings/race-and-ethnicity.

24. J. Semega et al., Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018, Current Population Reports (Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau, 2019).

25. M. Daly et al., “Optimal Indicators of Socioeconomic Status for Health Research,” American Journal of Public Health 92, no. 7 (2002): 1151–57.

26. L. Dettling et al., “Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” FEDS Note (blog), September 27, 2017.

27. E. Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 2016).

28. R. Elving, “With Latest Nativist Rhetoric, Trump Takes America Back to Where It Came From,” NPR, July 16, 2019.

29. A. Constante, “Filipino American Nurses, Reflecting on Disproportionate Covid Toll, Look Ahead,” NBC News, June 4, 2021; and J. Glovert, “‘None of Us Signed Up to Die’: Filipino American Nurses Disproportionately Impacted by COVID-19,” ABC News 7, May 10, 2021.

30. W. McKinley, December 21, 1898, presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-132.

31. C. Choy, Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003).

32. J. Nazareno et al., “From Imperialism to Inpatient Care: Work Differences of Filipino and White Registered Nurses in the United States and Implications for COVID-19 Through an Intersectional Lens,” Gender, Work & Organization 28, no. 4 (July 2021): 1426–46.

33. P. Cachero, “From AIDS to COVID-19, America’s Medical System Has a Long History of Relying on Filipino Nurses to Fight on the Frontlines,” Time, May 30, 2021.

34. M. Zhu, The Page Act of 1875: In the Name of Morality, SSRN, March 23, 2010.

35. W. Pettersen, “Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” New York Times Magazine, January 9, 1966.

36. D. Geary, “The Moynihan Report: An Annotated Edition,” The Atlantic, September 14, 2015.

37. K. Chow, “‘Model Minority’ Myth Again Used as a Racial Wedge Between Asians and Blacks,” Code Switch, NPR, April 19, 2017.

38. Asian Americans Advancing Justice, A Community of Contrasts: Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the West (Los Angeles: AAAJ, 2015), advancingjustice-aajc.org/sites/default/files/2016-09/AAAJ_Western_Dem_2015.pdf.

39. S. Woolf and H. Schoomaker, “Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959–2017,” JAMA 322, no. 20 (2019): 1996–2016; and E. Arias, B. Tejada-Vera, and F. Ahmad, “Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for January Through June, 2020,” NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release, Report No. 010, February 2021.

40. S. Woolf, R. Masters, and L. Aron, “Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic in 2020 on Life Expectancy Across Populations in the USA and Other High Income Countries: Simulations of Provisional Mortality Data,” BMJ 373 (2021): n1343.

41. E. Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

42. C. Strickland, I. Karaye, and J. Horney, “Associations Between State Public Health Agency Structure and Pace and Extent of Implementation of Social Distancing Control Measures,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 27, no. 3 (2021): 299–304.

43. T. Klaiman and J. Ibrahim, “State Health Department Structure and Pandemic Planning,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 16, no. 2 (2010): e1.

44. H. Xu and R. Basu, “How the United States Flunked the COVID-19 Test: Some Observations and Several Lessons,” American Review of Public Administration 50, no. 6–7 (2020): 568–76.

45. B. Murphy and L. Stein, “COVID-19: CDC Director Buckled to Politics, Tarnishing Agency,” USA Today, November 11, 2020.

46. J. Koplan et al., “The CDC Was Damaged by Marginalization and Politicization. This Is How Biden Can Fix It,” NBC News THINK, January 14, 2021.

47. K. Finegold et al., “Trends in the U.S. Uninsured Population, 2010–2020,” Issue Brief, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Health Policy, February 11, 2021, aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/265041/trends-in-the-us-uninsured.pdf.

48. W. Hossain et al., “Healthcare Access and Disparities in Chronic Medical Conditions in Urban Populations,” Southern Medical Journal 106, no. 4 (2013): 246–54.

49. Xu and Basu, “How the United States.”

50. Xu and Basu, “How the United States.”

51. L. Mishel, The Enormous Impact of Eroded Collective Bargaining on Wages (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, April 8, 2021).

52. R. Yearby and S. Mohapatra, “Structural Discrimination in COVID-19 Workplace Protections,” Health Affairs Blog, May 29, 2020.

53. M. Honey, “Martin Luther King and Union Rights,” Clarion, PSC CUNY, April 2011.

54. P. Frymer and J. Grumbach, “Labor Unions and White Racial Politics,” American Journal of Political Science 65, no. 1 (2021): 225–40.

55. W. Barber et al., “A Moral Policy Agenda to Heal and Transform America: The Poor People’s Jubilee Platform,” Poor People’s Campaign, July 2020, poorpeoplescampaign.org/about/jubilee-platform.

56. A. Modestino et al., “Childcare Is a Business Issue,” Harvard Business Review, April 29, 2021.

57. Yearby and Mohapatra, “Structural Discrimination.”

58. K. Nowotny et al., “COVID-19 Exposes Need for Progressive Criminal Justice Reform,” American Journal of Public Health 110, no. 7 (2020): 967–68.

[Photo Credits: Alamy Stock Photo, John Davenport / San Antonio Express-News, Bob Nichols / USDA, Charles Edward Miller / flickr; Illustrations: Isabel Espanol]