Dr. Dena Simmons, the founder of LiberatED, is a leading voice on teacher education. She has written and spoken across the country about social justice pedagogy, diversity and emotional intelligence. On July 9, in a featured session with AFT Executive Vice President Evelyn DeJesus at the AFT’s TEACH conference, she shared strategies to cope with isolation, uncertainty, burnout and the collective traumas of the pandemic and the country’s ongoing racial reckoning.

Simmons opened her discussion with a quote from Martin Luther, who said, “Even if I knew that tomorrow, the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.” Thinking about that quote in terms of her work with social justice, Simmons acknowledged that we might not see the fruits of our labor, but we do it anyway; we plant the tree.

The pandemic has taken a toll on all of us, said Simmons, especially regarding health and education, where we have seen an increase in disparities. “They’ve always existed. But if we didn’t see them before, we see them now. We’ve all experienced high levels of anxiety, frustration … because there has been so much uncertainty,” she said, adding that many people have gotten sick or lost loved ones to COVID-19. All of this has had an impact on our stress levels.

In addition, there were families that we were unable to reach during the pandemic, said Simmons. She encourages us to pause and ask: What were we not doing before such that we were unable to reach those families? And she challenges us to ask, “What can we do now … to be better for those families that we serve?”

The COVID-19 pandemic has been our equity check, Simmons asserted. “This has been an opportunity for us to reflect, for us to see what we were not doing well and for us to innovate. We saw how communities and corporations came together to provide for our young people, to support our teachers and our schools. And as we go into the next school year, we have to keep that same energy,” she said.

Simmons also noted that Black and Indigenous people in particular, and all people of color, have disproportionately suffered and died from COVID-19, while also dealing with overwhelming anti-Blackness on display. “Just as Black people are often triggered and experience a collective trauma when we see publicized anti-Black violence, you can also say the same is true for pandemic-related racial disparities,” said Simmons. She emphasized, “If we aren’t addressing racism, we aren’t addressing trauma.”

School is supposed to be a safe space. “To not be safe, to experience the trauma of racism,” said Simmons, damages Black students’ psyches, especially “through oversurveillance and policing.” She also asked what white children learn in our schools with white-centered curricula and in our society with so much anti-Black violence. “They learn how to unsee and devalue Black lives. They learn how to feel nothing about Black suffering.”

“Our work is to sit in the discomfort of what I’m saying here and to move past it and to work toward the social change that we need,” said Simmons.

The pandemic and the civil unrest have created heaviness for all of us, said Simmons. “There is a collective trauma that all of us are feeling. And for the teachers who are out there, even before the coronavirus, we were burnt out and stressed. … When teachers are stressed, students are stressed,” she said, adding that “a stressed and burnt out teaching force is an equity issue.”

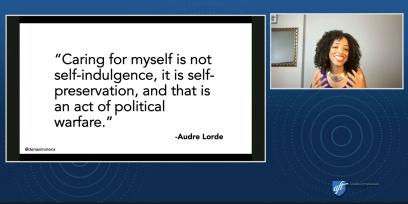

It’s essential for educators to indulge in self-care, said Simmons. “It is crucially important for us to take care of ourselves and for our school systems to take care of us so that we can take care of our students. Essentially, the first relationship we have is with ourselves.”

Simmons noted that self-care helps people manage what’s happening in the world, but it doesn’t dismantle systemic racism. With the increasing mental health challenges and the fervor for racial justice in the country, there has been a call for social and emotional learning (SEL), she said, further noting that while SEL is helpful, it (like self-care) will not solve racism. Simmons calls for an equity and anti-racist lens for SEL because our educational system is founded on the ideals of whiteness. If we don’t carefully consider this context, we risk “SEL turning into white supremacy with a hug.”

Simmons encouraged educators to initiate the effort to dismantle the oppressive structures in schools. When people ask where to begin, Simmons tells them to start and don’t stop “because racial justice is not something you can do overnight.” You can’t just check a box, read books or serve on a racial justice committee. As Simmons says, even for her as a Black woman, “It is a practice. I am learning every single day.”

At the end of Simmons’ presentation, AFT Executive Vice President Evelyn DeJesus shifted the session to a roundtable that featured paraeducator Cheryl Shuff and school social workers LaCresiea Olivier and Josephine Shelton-Townes. These educators weighed in on Simmons’ discussion of social and emotional learning.

“I took a lot of notes. … Dr. Simmons was just on point about a lot of different things,” said Shelton-Townes. “We have to get real with ourselves, sit back, take a look and begin to digest our belief systems and how we perceive things and how that impacts our ability to teach and also even to learn from kids.”

When asked about how they have used social and emotional learning in their professional practice, Shuff said it is often a peer educator who uses social-emotional learning to address students’ behavior when the teacher is unable to.

Olivier agreed, explaining that when you start teaching the students and helping them identify feelings and emotions, and what was going on inside them, it helps build connections. “Social-emotional learning is not about just what we can teach them, but what they can teach us as well, to be able to develop a communication between each other and an understanding, … [including] wanting to learn from one another.”

[Adrienne Coles]