I started practicing emergency medicine when I was 27 years old, and I still remember the vulnerability of the people who came to see me. They were sick or injured, frightened, and asking for help. They didn’t know me, and yet they put their trust in me. I did everything in my power to help them and yet, even then, I sometimes failed.

As an ER doctor, being unable to save a life was devastating. The walk across the hall to the small room where family and friends waited always felt like a long hopeless journey. Yet while this poignant intersection of compassion and mortality is difficult, it is that very compassion, and the humility and caring involved, that drew many of us into healthcare in the first place.

Today, much of that compassion is being stripped away. Early in my career, in the 1970s, we had time to build the kind of personal relationships with our patients that often contributed as much to their health and well-being as the medical treatments we prescribed. Sadly, the space in which to cultivate these deeper relationships seems to be slipping away—lost to an electronic medical record that is as much about billing as about caring, and to an impersonal corporate structure that prioritizes revenue generation over a deeper understanding of the social and economic circumstances that contribute to illness.

I became a doctor to improve people’s health and well-being, not just to treat their medical conditions. I soon realized, however, that in many cases I was treating the medical complications of social problems. I was trained to treat the medical conditions, which I did to the best of my ability; but afterwards, my patients returned to the same social conditions that had brought them into the hospital in the first place. I eventually realized that our healthcare system is designed not to support wellness but rather to profit from illness. While most healthcare providers certainly don’t approach caring for people that way, the underlying business model does.

Serving in public office while still practicing medicine gave me another insight: the realization that the more money we spend on healthcare, the less is available for housing, nutrition, education, or other things that are critical to health and well-being. Since first running for the Oregon legislature in 1978, I have spent 26 years as a representative, as a senator, and as governor trying to develop a new model—one built on the recognition that health is the product of many factors, only one of which is medical care.

In 2012, in the depths of the Great Recession, Oregon established such a model: coordinated care organizations (CCOs) for our Medicaid recipients. The CCOs don’t just treat illness; they cultivate health by addressing not only physical, mental, and dental care but also related needs such as safe housing, transportation, and fresh, affordable food. CCOs have also demonstrated that it is possible to expand coverage and reduce the rate of medical inflation while improving quality and health outcomes. Now, with the deep recession triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, it is time to scale this kind of model up for the whole nation. My primary aim with this article is to offer one way in which we might achieve that goal.

From Cost and Coverage to Value and Health

For decades, the healthcare debate throughout the United States has focused almost entirely on coverage—on how to pay for access to the current system—rather than on health. What is missing is a consideration of value, which in this context means that the purpose of the system is not simply to finance and deliver medical care but rather to improve and maintain health. Indeed, the things that have the greatest impact on health across the lifespan are healthy pregnancies, decent housing, good nutrition, stable families, education, steady jobs with adequate wages, safe communities, and other “social determinants of health”;1 in contrast, the healthcare system itself plays a relatively minor part.

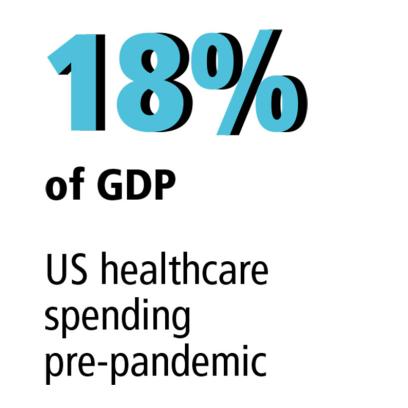

Ironically, since the cost of medical care consumes 18 percent of our gross domestic product (GDP), our current healthcare system actually undermines our ability to invest in children, families, housing, economic opportunity, and the many other key social factors important to health and well-being. This is a primary reason why the United States does not compare favorably in terms of health statistics with nations that choose to spend far more on the social determinants and far less on the healthcare system.2

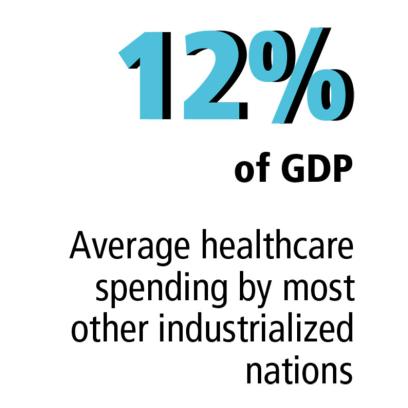

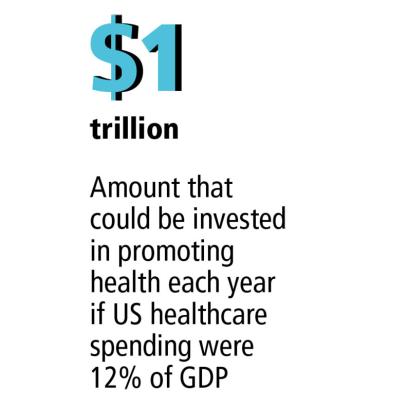

If we could reduce our healthcare spending from 18 to 12 percent of GDP (which is the average spent by most other industrialized nations), we would free up over one trillion dollars a year to invest in the things that contribute more to health.3 Such a reduction in spending might seem impossible, but successful examples of how to bring down the total cost of care do exist, including Oregon’s CCOs. Under these care models, providers receive a fixed amount of money (a global budget) to provide quality care with good outcomes for a defined population; if the global budget is exceeded in any given year, the providers are at financial risk for the difference. These care models change the system’s incentives from rewarding sickness to rewarding wellness—and they work. Because they focus on improving health, they prevent illnesses and thereby reduce costs without sacrificing quality.4

Effectively addressing the access, value, and cost issues in our healthcare system is one of the most important domestic challenges we face as a nation. Doing so, however, requires both a clear-eyed assessment of what this system has become and the courage to challenge that system. The global pandemic, with its profound economic and social consequences, has brought into clear focus the urgent need for a new model more aligned with caring, compassion, and the goal of improving the health of our nation. And no one is more qualified to lead that effort than the people who have dedicated their lives to the healthcare profession.

COVID-19 and Our Legacy of Inequity

In 1882, the newly formed Populist Party wrote in its platform, “The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind.”5 Now, over 125 years later, these words aptly describe our current social and economic conditions and how little progress we have made in terms of social justice and equal opportunity. The novel coronavirus has exposed anew the inequities and the linked class and race divisions within our society, problems that have been with us since before our nation’s founding, almost always churning just below the surface, visible only indirectly when we examine disparities like disproportionately lagging health and education outcomes for chronically under-resourced—and often racially or ethnically segregated—communities. Especially in the past few decades, these inequities have been masked by debt-financed economic growth that has prevented us from mustering the political will and societal solidarity necessary to address them.

Perhaps nothing better illustrates the depth of these disparities, or the extent to which social justice has been eroded, than the US healthcare system. It is a massive corporate enterprise that now consumes nearly one-fifth of our GDP, a huge employer that is increasingly dependent on public debt for its financial stability, and a major driver of income inequality. The pandemic has cast these inequities and contradictions into stark relief.

We see the difficulty nonmedical essential workers have had in obtaining adequate health protections, often resulting in significantly higher rates of infection.6 These are people in low-wage positions—often with minimal or no sick leave or insurance—working in grocery stores, warehouses, factories, and food and agricultural production sites.7 We also see that Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 in dramatically disproportionate numbers—deaths attributable to the structural inequities in our society that make Black people and other people of color more likely to have diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure, and to live near major sources of health-endangering pollutants and far from health facilities and grocery stores.8 These are issues we urgently need to address.

At the same time, as I discuss later, the pandemic has for the first time brought the economic interests of those who pay for, consume, and provide healthcare into clear alignment. This gives us a once-in-a-generation opportunity to transform the current system by demanding value as well as universal coverage and by constraining the total cost of care. Let’s examine each of these issues, starting with the difference between coverage and value.

Coverage versus Value

We all know what coverage means—it means having the ability to pay the cost of healthcare without suffering economic hardship, without crippling copayments and deductibles, without having to choose between paying for prescriptions and paying for rent, without fear of surprise billings. Value is something else entirely.

Value is the recognition that not only must all Americans have coverage, but that the care they receive, and the system through which they receive it, must produce value in terms of health outcomes. Value presumes that we should not be spending limited public resources on overtreatment, inflated prices, or care that is unnecessary, inefficient, or ineffective. Most of all, value means doing more to address the factors that have by far the greatest impacts on health, especially the conditions of injustice that underlie disease: poverty, hunger, unemployment, the erosion of community, and the lack of hope. Let me offer a tragic example from my own state, changing only the names to protect the privacy of those involved.

Susan was born into a troubled family. She was sexually and physically abused by her alcoholic father and fled from her home to the streets of Portland. Alone, homeless, looking for love and somewhere to belong, she continued to be victimized, abusing alcohol herself and becoming pregnant at 17. Without any prenatal care or support systems, she gave birth prematurely to her daughter, Patty, who was diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome.

Homeless and struggling with addiction, Susan placed Patty for adoption. But the cycle was not broken. Patty was diagnosed with depression and multiple mental disorders. Although she was briefly adopted, she subsequently had 26 different foster placements before being admitted to a residential mental health facility, where she now lives. All of this happened before her 10th birthday.

There is no way to measure the depth of this tragedy. The tragedy of a young, abused mother who battles substance abuse and will never know her daughter. The tragedy of a child who is likely to live out her life within the walls of an institution. And the tragedy of knowing that we could have prevented this outcome but failed to do so. If we had a healthcare system designed to maximize value, we would be addressing the social determinants of health that could have given Susan and Patty opportunities to live very different kinds of lives.

If we hope to turn this around, we must focus on four key aspects of our current healthcare system: public resources, our national debt, income inequality, and the important difference between health and healthcare. We must also understand and overcome the major obstacles preventing meaningful reform.

Public Resources

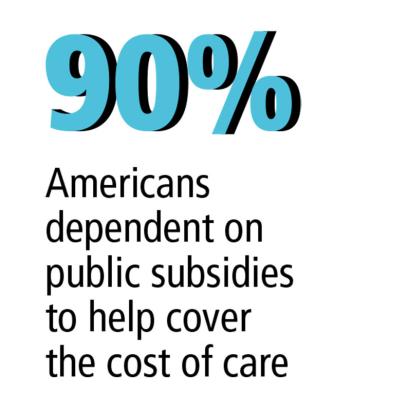

First, we need to understand the central role of public dollars in our healthcare system. Healthcare is the only economic sector that produces goods and services which none of its customers can afford. This system only works because the cost of medical care for individuals is heavily subsidized with public resources. This happens directly through public programs like Medicare and Medicaid. It also happens indirectly through the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance and through the public subsidies in the individual insurance market established through the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

As a result, about 90 percent of Americans depend on public subsidies to help them cover the cost of their care9—all except the 28 million Americans who remain uninsured.10 These people are not eligible for a public subsidy themselves, but through their taxes they help subsidize the cost of healthcare for everyone else. This egregious situation reflects the systemic inequality that exists not only in our healthcare system but also across our whole society.

Thus, the central issue in the healthcare debate involves the allocation of public resources, which represent a kind of fiscal commons. They are shared resources raised from society as a whole—and they should be allocated in a way that benefits all of us, not just some of us.

The National Debt

We also need to recognize that our healthcare system is increasingly financed with debt. Why? Because public resources are finite and Congress is borrowing ever more money to pay for existing programs and services—including healthcare. This fact is reflected in the congressional budget deficit and in our national debt. The national debt is the accumulation of years of budget deficits and represents the amount of money that has been borrowed to cover the difference between congressional spending and the tax revenue available to pay for it. Since healthcare now accounts for over 28 percent of the federal budget not spent on interest—and is projected to grow to 33 percent by 202811—it has become a major driver of the national debt.

This means that as the population ages and the cost of care continues to rise, the economic viability of the healthcare system will increasingly depend on borrowing money—and on the capacity of the federal government to absorb more debt. If the capacity to borrow is constrained, the financial underpinnings of the healthcare system begin to unravel. Because COVID-19 has created exactly this constraint on borrowing, a healthcare financing crisis that was on the horizon is now at our door.

Income Inequality

Furthermore, a growing share of the money borrowed to prop up our medical system is not being used to expand coverage. Instead, it is enriching the profits of large corporations and wealthy individuals.12 Let me be very clear: our current healthcare system is increasing income inequality through a process called rent seeking. This occurs when powerful stakeholders manipulate public policy to increase their own wealth without the creation of new wealth (i.e., they take more of the pie without making the pie bigger). For example, when the pharmaceutical industry convinced Congress to prohibit the government from negotiating drug prices for the 60 million Americans on Medicare, it distorted the market by putting the power in the sellers’ hands to set whatever prices they wish. After many news stories about “big pharma,” more people have become aware of concerns with drug prices. What seems to be less well known is just how profitable medical insurance is: in 2019, the seven largest for-profit insurers had combined revenue of over $900 billion13 and profits of $35.6 billion, a 66 percent increase over 2018.14 The result of the rent seeking that is evident throughout the healthcare industry is lower disposable income for the individuals who have to pay those inflated prices, increased profits, and wider income inequality.

Health versus Healthcare

Finally, we need to recognize that the goal of the healthcare system should be to keep people healthy, not just to finance medical care. In other words, it needs to address the social determinants of health—access to healthy food and clean water, safe housing, a reliable living wage, family and community stability, and more—which have a far greater impact than medical care on the health of both individuals and communities. Yet the ever-increasing cost of care compromises our ability to invest in these things.

Today, healthcare providers and the system have different goals. While most care providers are trying to enhance people’s health, they nevertheless work in a system where the incentives are to increase profits and redistribute more wealth to the wealthy.

Confronting the Total Cost of Care

Improving health requires a financially sustainable system that ensures that all Americans have timely access to effective medical care

and that makes long-term investments in the social determinants of health. To achieve these dual goals requires five core elements:

- Universal coverage;

- A defined set of benefits;

- A delivery system that assumes risk and accountability for quality and outcomes;

- A global budget indexed to a sustainable rate of growth; and

- A cost prevention strategy that allocates some of the savings to addressing the social determinants of health.A system that incorporates these elements can take many forms, but without all five we cannot achieve our goal of improving health in a financially sustainable way.15

There are two primary obstacles keeping us from moving toward a new system focused on value and health: the way the debate has been framed, and the cost-shifting strategies that—until the pandemic—allowed us to avoid the growing discrepancy between the cost of the system and our ability to pay for it.

How the Debate Is Framed

For decades, the national healthcare debate has been paralyzed largely because neither Democrats nor Republicans have seriously challenged the underlying healthcare business model—the debate has been over what level of funding to provide. The current business model is built around fee-for-service reimbursement, in which providers are paid a fee for every service rendered. The more they do, the more they get paid. And since the fees paid for medical services usually are not linked in a meaningful way to a positive health outcome for the person receiving the care, the system incentives are aligned with maximizing revenue rather than maximizing health.

The Affordable Care Act attempted to move away from this model with incentives to participate in accountable care organizations (ACOs), which are networks of providers that shared in savings if they delivered care more efficiently (called upside risk). The problem is that the ACOs were not required to assume any significant degree of downside risk, in which they had to refund a payer if the actual costs of care exceeded a financial benchmark. Furthermore, the ACA did not take on the rent seeking (transferring wealth to the wealthy) that accounts for so much of the cost in the system. As a consequence, the cost of healthcare grew from $2.6 trillion in 2010 to $3.6 trillion in 2019.

In the wake of the Affordable Care Act, both major political parties have continued to debate only the extent to which we should fund the system, creating a false choice between cost and access. This false choice is reflected in the Republican view that the cost of healthcare is unsustainable and must be constrained, and in the Democratic view that any reduction in spending will result in a reduction in access. Both sides are right, if they remain wedded to the current business model. Republican proposals to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act, for example, would simply reduce the public subsidies in the current business model, increasing the number of uninsured Americans and exacerbating the inequity that already exists. Democratic efforts to expand coverage through proposals like Medicare for All would significantly increase public subsidies but within the same inflationary fee-for-service business model, adding to the burden of debt that future generations will have to pay. To put it another way, Republican proposals increase inequity and harm people today; Democratic proposals increase the debt and harm people tomorrow.

Cost-Shifting Strategies

Framing the debate in this way allows legislative bodies to avoid directly addressing the cost of care by simply shifting that cost somewhere else, a strategy used by other third-party payers (insurance companies and employers). As the total cost of care increases, instead of seeking to reduce it, these payers take actions that shift the cost to individuals, who cannot afford it, or to future generations. Here are the most common cost-shifting strategies:

- Reducing eligibility, cutting benefits, and/or raising copayments and deductibles—all of which shift costs to individuals;

- Reducing provider reimbursement, which may result in efforts by providers to avoid caring for those who cannot pay and/or lead to increased fees by providers when they are caring for people who are insured; and

- Increasing debt-financed public subsidies, which shifts the burden to our children and grandchildren.

Importantly, none of these cost-shifting strategies reduce the total cost of care, which is the central structural problem in our system. Before COVID-19, we were able to rely on these strategies, particularly debt-financed public subsidies, to avoid the difficult choices necessary for a solution. But given the economic crisis we now face, we must directly confront the total cost of care. Fortunately, this gives us the opportunity to pursue new strategies that both redesign the current hyperinflationary business model and invest in those things that have the greatest impact on health and well-being.

Constraining Cost without Sacrificing Value

At long last, we have the opportunity to set aside the circular, dead-end debate about cost and coverage and to engage in a new discussion of value and health. This frees us to begin building a new system that offers universal coverage and caps the total cost of care while holding provider networks accountable for quality and outcomes. Instead of taking pressure off the old system through cost-shifting strategies, we must demand that the new system deliver value through cost-prevention strategies that include both the provision of affordable, effective medical care and sustained investments in the social determinants of health. And instead of the system profiting from illness, we must create a new incentive structure that rewards health.

To achieve this requires moving from fee-for-service to capitated payment models, in which providers receive a fixed payment (the capitation rate) for each person enrolled in a health plan. The aggregate of these individual rates forms a global budget for all those enrolled in the plan, and this budget is then indexed to a sustainable growth rate. Because providers are paid per enrollee rather than per service, this model rewards them for helping patients achieve wellness and adopt healthier lifestyles (i.e., require fewer services). At the same time, providers are held accountable for meeting clear quality and outcome measures; if the global budget is exceeded in any given year, the providers are at financial risk for the difference (i.e., they assume downside risk). In short, while the fee-for-service payment model rewards overutilization and sickness, the capitated payment model rewards efficiency and wellness. Oregon’s coordinated care organizations (CCOs), established in 2012, demonstrate one way this can be accomplished.

The coordinated care organizations emerged from the Great Recession when Oregon was faced with high unemployment, falling tax revenues, and a huge budget shortfall in Medicaid because of increased enrollment. Instead of resorting to the traditional cost-shifting strategies, a new care model was created that sought to get more value—more health—for each dollar spent. CCOs are community based and are designed to move beyond a narrow clinical model to focus more broadly on community health. The total cost of care is capped in a global budget that can grow by no more than 3.4 percent per person per year. While maintaining enrollment and benefits, providers are required to meet strong measures of quality, health outcomes, and patient satisfaction.

During the first five years, 2012 to 2017, Oregon’s CCOs met the required outcome and quality metrics, operated within the growth cap, expanded enrollment by over 385,000 people, and realized a cumulative total savings of over $1 billion. Prior to COVID-19, savings were projected to reach $8.6 billion over a decade—creating a pool of resources to reinvest in the social determinants of health, thereby further reducing the need for medical care. The Oregon CCO experience clearly demonstrates that it is possible to expand access, reduce the rate of medical inflation, and increase value.

The Oregon experience also demonstrated that we cannot fully address the total cost of care by focusing on only one part of the system. Oregon’s CCOs were created for Medicaid recipients, but since the rest of the system still followed the old model, many cost-shifting strategies were still available. For example, providers can still compensate for the 3.4 percent per member per year growth cap required by the CCOs by increasing what they charge employers (resulting in increased costs in the commercial health insurance market). To truly address our healthcare and health crises, the United States needs a holistic approach that extends the new health-focused model into the commercial market.

A New Model for the Nation

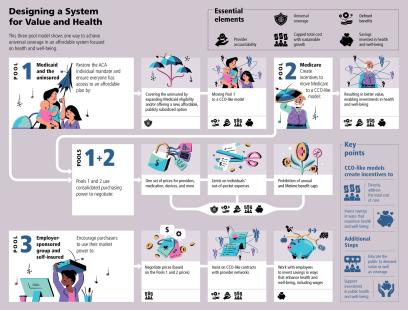

As discussed earlier, a financially sustainable system designed for value and health can take many forms, but it must include these five core elements:

- Universal coverage;

- Defined benefits;

- Assumption of risk by providers and accountability for quality and outcomes;

- Capped total cost of care through a global budget indexed to a sustainable growth rate; and

- Cost prevention by addressing the social determinants of health.

Here is one example of what a model with these five elements could look like.

Starting with our current public-private financing structure, modify the three large insurance pools that currently define the US healthcare system.

- Pool 1: To achieve universal coverage (element 1), restore the ACA individual mandate but ensure that people have affordable health plans in which to enroll. Expand Medicaid eligibility to include the 28 million people who are currently uninsured or create a new, affordable, publicly subsidized option to offer them. At the same time, move Pool 1 to a CCO-like capitated model that encompasses elements 2 through 5. If coverage in the individual market is unaffordable, those below a certain income level (e.g., 450 percent of the federal poverty level) could buy into Pool 1 with income-based cost sharing, which would make universal coverage more feasible. This is particularly important today as millions of people are losing their employment-based coverage and moving to Medicaid or the individual market.

- Pool 2: Because Original Medicare is still paid through fee-for-service, the program must be moved to a capitated model. One approach would be to create incentives to enroll in a Medicare Advantage Plan (most of which are already capitated) and change the Medicare Advantage Plans that are still fee-for-service to capitated models that meet elements 2 through 4. Because reimbursement would now be based on managing cost and improving health, Medicare Advantage Plans would better incentivize providers to view their patients more holistically through nutrition counseling, for example, or coordination with social services for safe housing, thereby meeting element 5.

- Pool 3: Allow the remaining markets—employer-sponsored medium and large group and self-insured markets—to operate as they do today, negotiating prices with health plans and using their market power to insist on capitated risk contracts with provider networks. The public sector price negotiations outlined below would provide a benchmark, giving employers additional leverage in negotiating prices in the commercial market. This advantage can be amplified by forming new partnerships with labor, as discussed below under

Continue the transformation by using the consolidated purchasing power of Pools 1 and 2 to negotiate one set of prices for both pools. This would include not only what providers are paid per beneficiary (risk-adjusted according to each beneficiary’s expected care needs) but also prescription drugs, medical devices, laboratory services, imaging, and all the other niche business models that have been established under the fee-for-service model to maximize revenue. This kind of price negotiation is what most large private employers (making up the majority of Pool 3) do today. Public payers should follow suit by using the consolidated purchasing power of the public sector—which is footing an ever-larger part of the bill—to get the best price and value for its constituents: the people of the United States of America. If the public sector were so inclined, it would also be possible to negotiate limits on individuals’ out-of-pocket expenses and to ensure there are no caps on annual or lifetime benefits.

The result would be a new system of universal coverage built on our current public-private financing structure. With the majority of Americans in some form of capitated risk model, this new system (1) reduces the total cost of care through price negotiations, a global budget indexed to a sustainable growth rate, and provider accountability for quality outcomes; (2) preserves consumer choice and allows current insurers to compete for Pools 1 and 2 in a restructured market; and (3) delivers more and more value and health because it requires strategic, long-term, effective investments in the social determinants of health.

I want to emphasize that this is merely one way to design a new, health-focused, financially sustainable system. There are others. My objective here is not to advocate for the example I have just outlined here, but rather to spark a new debate that will lead to a better system. Instead of being constrained by what currently exists, we need to start with our objective, agree on essential elements, and then let the contours of the new system emerge. Long-term, this will serve us better than starting with a plan that may not meet the criteria needed to achieve our goal. For example, while both Medicare for All and a public option are ways to achieve universal coverage (element 1), neither directly addresses the total cost of care (elements 3 and 4) or focuses on increasing investment in the social determinants of health (element 5). Surely, we can imagine linking the total cost of medical care to a sustainable growth rate within the next few years. Then we can work backward to create a health system that meets the objectives of Democrats by expanding coverage and improving health and meets the objectives of Republicans by reducing the rate of medical inflation through fiscal discipline and responsibility.

COVID-19 and the Urgency of Now

As the healthcare system has become ever more dependent on public debt, its financial underpinnings have become inexorably linked to the capacity of the government to borrow. That capacity has been suddenly and dramatically diminished by COVID-19 and by the business closures and high unemployment resulting from efforts to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

To prevent a complete collapse of the economy, there has been a massive federal intervention to keep credit flowing and to provide loan guarantees and direct payments to businesses and individuals. I believe we will have to spend at least $5 trillion this year alone to sustain our economic infrastructure and to support unemployed Americans. This will leave us with an unprecedented budget deficit and a national debt approaching $28 trillion—with little or no capacity to absorb the 60 percent growth in healthcare spending that is projected by 2028 (from $3.7 to $6.2 trillion), especially when prices for medical goods and services are projected to account for 43 percent of that growth.16

The pandemic is forcing us into an era of dramatic constraints on the public resources allocated to the healthcare system. Neither the government nor private-sector employers can afford the current system anymore, given the economic losses that both employers and individuals have experienced since February and the massive amount of public debt that has been accumulated just to hold our economy together. At the same time, those parts of the healthcare system that have been hit the hardest by COVID-19 are those most dependent on fee-for-service reimbursement, which exposes the basic flaw in a business model that depends on volume, regardless of the value of the services rendered.

This economic crisis means that, for the first time, the economic interests of workers, employers, the government, and many parts of the healthcare sector are aligned. The time to transform the system is now. We have crossed the Rubicon, and there is no going back. We can either watch our current system unravel, with millions more losing coverage and ever-widening income inequality, or we can work together to design a system that helps stabilize our economy and better serves the needs of the American people.

The Role of Labor

This is the moment for more states, facing huge general fund shortfalls, to move to a CCO-like care model for Medicaid, and for Congress, facing staggering debt, to create incentives for Medicare beneficiaries to enroll in a Medicare Advantage Plan and to move that program to a fully capitated model in which providers assume risk for quality and outcomes. Health professionals should be vocal advocates for both of these changes—and that advocacy should be backed up by the strength of the union movement to bring this model to the commercial market. This will require forging new alliances at the bargaining table between labor and payers—both public and private.

Coverage of the cost of healthcare is, of course, part of the total compensation package, which means that in collective bargaining, wages are often pitted against health benefits. For public employees, general fund appropriations for healthcare compete not only with general funds for wages but also for essentials like increasing nurse staffing ratios, reducing class sizes, and investing in housing and other social determinants of health. The traditional goal for labor in bargaining over healthcare is to reduce, to the greatest extent possible, out-of-pocket costs for union members (which is very important).

The problem is that focusing only on this aspect of the total compensation package—without questioning the cost structure, quality, or efficiency of the care being purchased—suppresses wage growth. Without aggressively challenging the cost structure and value of the healthcare being purchased, the dollars spent on rising premiums flow into a system that redistributes them upward, taking money from the pockets of working Americans to enrich the profits of large corporations and wealthy individuals (further exacerbating income inequality).

A CCO-like model would be better because it caps the total cost of care without sacrificing quality and it realizes savings to invest in the social determinants of health—including wages. Particularly for workers making minimum wage or close to it, income is a primary driver of health.17

Employees and employers have a shared economic interest in reducing the rate of medical inflation and in focusing on value and health. Providers, for the first time, now have an economic interest in changing the payment model from fee-for-service to capitated because this is the only way they can survive in an era that no longer can sustain debt financing. From the standpoint of the labor movement, CCO-like models could result in increased wages, better staffing ratios, and more funding for education and other services that are critical to making our society more just.

This latter point—the need for greater social investment—cannot be overemphasized. Reducing the total cost of care will lift up all working Americans (not just those with union representation) because it will make their wages go further and relieve them of the anxiety of not knowing whether the next illness will push them into bankruptcy. And it will give us, at last, the ability to address the conditions of injustice that underlie disease.

Seizing the Future

On April 5, 1968—the day after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated—Robert F. Kennedy delivered some brief remarks to the Cleveland City Club. His speech was about the stain of violence in America, but then he said,

There is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly, destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions; indifference and inaction and slow decay. This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is a slow destruction of a child by hunger, and schools without books and homes without heat in the winter.18

Schools without books, homes without heat, children without food, parents without jobs—these things fuel the creeping menace of despair and fading hope of a better future. These are cancers on the body of our community, and they have nothing to do with lack of access to the healthcare system—but rather with the cost of that system. It is our failure to demand value for the public dollars supporting the system that is directly responsible for our inability to treat the cancer, and thus our inability to give struggling Americans health, hope, and an equal opportunity for a better life.

In the words of Barack Obama, “Change will not come if we wait for some other person or if we wait for some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.”

Let's Begin Now

In this essay, I have argued that we need to reframe the healthcare debate from a narrow focus on coverage to a broader focus on value and on directly addressing the total cost of care. This is not to minimize the fundamental importance of coverage and access—an importance made clear by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exposed both the human cost of our lack of an explicit policy of universal coverage and the deep racial and ethnic health disparities that exist in our nation.

Now, when we as a nation are reckoning with the racism and inequity that structure our society and are focusing on reimagining what we might be, we have the opportunity to create real, lasting change in all of our systems, including healthcare—but we must address the root causes of the problems, not the symptoms. We need universal health coverage, but expanding coverage without demanding value for the public investment involved will only perpetuate an inequitable and unsustainable system that undermines our ability to invest in the social determinants of health.

Creating a new system with the five core elements (see "A New Model for a New Nation" above) will take time. But there is much we can, and must, do quickly. Because the economic consequences of the pandemic—particularly the increase in unemployment, with its associated loss of workplace-based coverage—are driving us toward Pool 1 (Medicaid, the uninsured, and the ACA marketplace), this is the logical place to start.

The most urgent coverage problem is for those who are not offered or have lost workplace-based coverage and whose income is too high for Medicaid (above 138 percent of the federal poverty level) but too low to afford the individual market. These struggling individuals are joined by a growing number of underinsured Americans who are technically covered by employer-sponsored plans but face copayments and deductibles so high that for all practical purposes they are uninsured. People of color—particularly Black, Hispanic, and Native American people—make up disproportionate numbers of both of these groups.

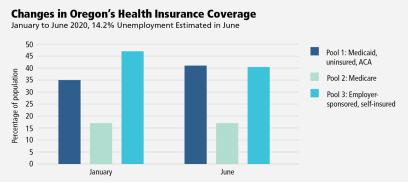

The state of Oregon offers an illustration of both the problem and the opportunity. By the end of April, 266,600 Oregonians had lost their jobs (an unemployment rate of 14.2 percent).19 An estimated 215,800 of these people will be eligible for Medicaid, 20,500 will move to the ACA exchanges, and 30,300 will remain uninsured.20 Because Medicaid is entirely financed with public resources and the ACA exchanges are heavily subsidized with public dollars, this amounts to a dramatic increase in public sector financing of healthcare. In terms of the healthcare model proposed in this essay, Oregon’s Pool 1 enrollees are expected to increase from 34.9 percent to 41.3 percent of the state’s population over the course of just a few months.

Furthermore, we know that if 80 percent of those who lack health coverage in Oregon made use of coverage for which they are currently eligible—Medicaid or the subsidies available through the ACA marketplace—the number of Oregonians who are uninsured would drop from almost 250,000 to 34,000 (from 6.2 percent to less than 1 percent).21 The only thing standing in our way is the total cost of care.

Since states are facing enormous budget deficits and the federal government is facing a looming debt crisis, it is imperative that shifts toward public financing be accompanied by effective mechanisms to reduce the total cost of care through global budgets (indexed to a sustainable growth rate, with providers at risk for quality and outcomes). At the same time, such global budgets are now more appealing to many hospitals and primary care practices because of the sharp loss of revenue among those with fee-for-service models.

The convergence of these factors creates a significant opportunity to begin transformation of the healthcare system through Pool 1. We can address both cost and access. Let’s not wait any longer.

John A. Kitzhaber, MD practiced emergency medicine for 15 years and spent nearly four decades in public service in Oregon’s state legislature and then as Oregon’s longest-serving governor (1995–2003 and 2011–2015). The author of the Oregon Health Plan and architect of Oregon’s coordinated care organizations, he is now a writer, speaker, and consultant on health policy.

Endnotes

1. L.M. Nichols and L.A. Taylor, “Social Determinants as Public Goods: A New Approach to Financing Key Investments in Health Communities,” Health Affairs 37, no. 8 (Winter 2018), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0039; and A. Ohanian, “The ROI of Addressing Social Determinants of Health,” American Journal of Managed Care, January 11, 2018, https://www.ajmc.com/contributor/ara-ohanian/2018/01/the-roi-of-address….

2. C.M. Hood, K.P. Gennuso, G.R. Swain, and B.B. Catlin, “County Health Rankings: Relationships between Determinant Factors and Health Outcomes,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 50, no. 2 (February 2016): 129-35, www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmsa073350.

3. S.M. Butler, D.B. Matthew, and M. Cabello, “Re-Balancing Medical and Social Spending to Promote Health: Increasing State Flexibility to Improve Health through Housing,” February 2017, www.brookings.edu/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2017/02….

4. Institute of Medicine, Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance, ed. K.N. Lohr (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 1990), https://doi.org/10.17226/1547; the Institute of Medicine defines quality as “the degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”

5. N.A. Hamilton, Rebels and Renegades: A Chronology of Social and Political Dissent in the United States (Routledge, 2002).

6. J.W. Dyal, M.P. Grant, K. Broadwater, et al., COVID-19 Among Workers in Meat and Poultry Processing Facilities—19 States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 2020).

7. R. Brandom, “Workers from Amazon, Instacart, and Others are Calling In Sick to Protest Poor Virus Protections,” The Verge, May 1, 2020, www.theverge.com/2020/5/1/21243905/mayday-strike-boycott-amazon-target-…; T. Kenney, “Tyson Meat Plant in Iowa Reports More Than 700 Employees—or 58%—Have Coronavirus,” Kansas City Star, May 5, 2020, www.kansas

city.com/news/coronavirus/article242519791.html; and T. Sandys, “‘It Feels Like a War Zone’: As More of Them Die, Grocery Workers Increasingly Fear Showing Up at Work,” Washington Post, April 12, 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/12/grocery-worker-fear-death-co….

8. “COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified April 22, 2020, www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-….

9. M. Mikluic, “Medicare Statistics and Facts,” Statista, May 15, 2020, www.statista.com/topics/1167/medicare/; M. Mikluic, “Medicaid Statistics and Facts,” Statista, May 4, 2020, www.statista.com/topics/1091/medicaid/; “Distribution of the Nonelderly with Employer Coverage by Age,” Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018, www.kff.org/private-insurance/state-indicator/distribution-by-age-3/?cu…; and “Marketplace Enrollment 2014–2020,” Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020, www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-enrollment/?curre….

10. J. Tolbert, K. Orgera, N. Singer, and A. Damico, “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population,” Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2019, www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-populat….

11. “American Health Care: Health Spending and the Federal Budget,” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, May 30, 2018, www.crfb.org/papers/american-health-care-health-spending-and-federal-bu….

12. A. Case and A. Deato, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020); and E. Rosenthal, An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became Big Business and How You Can Take It Back (New York: Penguin Books, 2017).

13. E. Payne, “Top Health Insurers’ Revenues Soared to Almost $1 Trillion in 2019,” BenefitsPRO, February 24, 2020, www.benefitspro.com/2020/02/24/top-health-insurers-revenues-soared-to-a….

14. S. Livingston, “Publicly Traded Health Insurers Have Taken Over,” Physicians for a National Health Program, February 18, 2020, https://pnhp.org/news/publicly-traded-health-insurers-have-taken-over/.

15. J. Kitzhaber, “Reframing the 2020 Health Care Debate,” Progressive Policy Institute, July 2019, www.progressivepolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/GK_AK_HealthcareFi….

16. “NHE Fact Sheet,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure, April 24, 2020, www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-….

17. K. Krisberg, “Income Inequality: When Wealth Determines Health: Earnings Influential as Lifelong Social Determinant of Health,” The Nation’s Health 46, no. 8 (October 2016): 1–17, http://thenationshealth.apha

publications.org/content/46/8/1.1.

18. Robert F. Kennedy, “Remarks to the Cleveland City Club, April 5, 1968,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family/robert-f-kennedy/….

19. M. Rogoway, “Oregon’s Unemployment Rate Skyrocketed to 14.2% in the First Month of the Coronavirus Outbreak,” Oregonian, May 19, 2020, www.oregonlive.com/business/2020/05/oregons-unemployment-rate-skyrocket….

20. COVID-19 Impact on Medicaid, Marketplace, and the Uninsured, by State (Washington, DC: Health Management Associates, 2020), www.healthmanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/HMA-Estimates-of-COVID-Impa….

21. Oregon Health Authority, “Many Oregonians Who Lack Health Coverage Are Eligible for Premium Subsidies, Oregon Health Plan,” September 6, 2018, www.oregon.gov/oha/ERD/Pages/NewReportManyOregoniansWhoLackHealthCovera….

[illustrations by Manuel Bortoletti]