Exposure to traumatic events in childhood and adolescence can have lasting negative social, emotional, and educational effects. For schools, or any environment that serves children, to be truly trauma-informed, they must address three crucial areas: safety, connection, and emotional and behavioral regulation. This article, which is excerpted from our book Creating Trauma-Informed Schools: A Guide for School Social Workers and Educators, will explore these three areas as the foundational pillars of a trauma-informed school environment.

Safety

At their core, all traumatic events

are a violation of a sense of safety in the world and with others. People and places that are supposed to be attuned to the needs of children are often the ones that violate trust through abuse, neglect, and violence. Given that the caregiver-child relationship is the foundation on which the child’s senses of safety, competence, and self-containment are built, when this relationship is strife with traumatic events, those capacities are severely compromised.

1 Abusive parents and caregivers, violence in communities, and shootings in schools

* are all too commonplace in American culture. The presence of traumatic stress has long-lasting negative impacts on children, and when severe and prolonged, it can be so toxic that it leads to neurological and biological health problems.

2

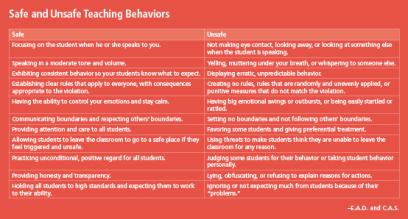

What does safety look like? For children and adolescents, safety is felt through connections with people who have a calm and focused presence. They are attuned to the child’s actions, words, and nonverbal communications and respect the child’s boundaries and rights. Power and control are essential to safety in that the child is allowed to be in charge of himself or herself as much as is developmentally appropriate. When power is used to be punitive and demeaning, children do not feel safe. When seeking safety, children look for someone to be predictable and consistent. Following through on what they say they are going to do and avoiding chaotic and disorganized behaviors are essential to safety. All these require the person to stay calm, regulated, and focused when the child is dysregulated, out of control, or even aggressive. Some examples of safe and unsafe behaviors in a school setting can be found in the graphic below.

click the image to enlarge

Classrooms that feel safe to children are those that have clear expectations, well-defined routines, time for transition, choices whenever possible, and attuned teachers. Specific events in the classroom can serve as reminders of previous traumatic and therefore unsafe experiences. These current events trigger reminders of past events.3 Some examples of triggers in a classroom setting that can prompt a child to react from a place of traumatic stress and feeling unsafe are:

- Sensory reminders of the trauma—smells, sounds, or images that remind the child of a person, place, or time that is connected to a traumatic event.

- Touch—whether to focus the child with a gentle hand on the shoulder or a physical restraint of a child who is a danger to others. Touch that is unwanted or unexpected can be a trauma trigger.

- Fighting, arguing, or yelling, whether between children or between an adult and a child.

Some triggers can be managed by decreasing certain behaviors, such as yelling by the teacher or adult in charge, but others can be difficult to anticipate and manage because one cannot predict what a trigger might be for a specific child. For example, a child may have a traumatic stress reaction when triggered by the smell of an orange. Perhaps that child was abused by a caregiver who regularly ate oranges, and the smell of the orange being peeled reminds the child of that person and the abusive behavior.

A teacher would have no way of anticipating this, and the child may not even be aware that the smell of the orange is a trigger until that moment when the child is emotionally reactive, out of control, or dissociative. What teachers can do is be curious about what may have prompted the sudden change in that child and include a traumatic trigger as one of the possible explanations for the behavior. They also may pick up clues to triggering events by listening carefully to the way children discuss subjective experiences. There are signs about how a child primarily receives, interprets, and transmits sensory stimuli and expresses them in terms of sight (visual), sound (auditory), touch (kinesthetic), smell (olfactory), and taste (gustatory).4 Does a child use representational language that pictures, hears, feels, whiffs, or flavors an experience that may be helpful in recognizing how a child is triggered? Trauma-informed practices mean being compassionate and seeing behaviors and actions as attempts to express distress and seek safety.5 Current events provide ample evidence of how important it is to understand the impact of violence on child development and learning.

Connection

Children who have had traumatic experiences inflicted on them by adults learn that adults are not to be trusted. Children entering a new school or a new classroom will be careful around adults and will watch closely for indications that they need to protect themselves. This sense of hypervigilance and wariness will make it difficult for them to connect with adults in a school setting, but connection is essential for the development of safe, trauma-informed settings.6 Power imbalances also disrupt connection. In the classroom, teachers are in charge and make the rules, which can lead children to feel powerless. If a child has experienced an adult using his or her power to abuse others, this power imbalance will impair connection. It may also create a situation in which the child seeks power and control to feel safe, which creates disconnection.7 In trauma-informed classrooms, teachers recognize this dynamic and strive to create corrective experiences with an adult who is associated with positive experiences. Trauma can be re-enacted in relationships with adults who react to the child’s search for safety, power, and control with anger, punishment, suspicion, and distance.8

Adults can get drawn into a trauma re-enactment with a child who is testing them to learn how they respond. Often, this is not done purposefully but instead comes from a defensive, self-protective action when a child engages as he or she would with the abusive adult. In other words, in order to know what to expect and to confirm the child’s suspicion that the adult is unsafe, the child may engage in a conflictual way. This can be done through behavior that is aggressive or unsafe, verbal assaults designed to hurt or bring about rejection, or mistreatment of another child in the classroom. This child will often be described as being “provocative” or “self-sabotaging,” but it is important to not label but rather to wonder why. Why would this child behave this way? When this is seen as a traumatic reaction, a self-protection against vulnerability and being harmed yet again by an adult the child is supposed to trust, it makes sense. It is a survival behavior. When viewed in this manner, it can be helpful in not personalizing the behavior. When the adult does not respond as expected, then there is hope for safety.

In order to establish connection in school settings, it can be helpful to start off the school year by setting some ground rules for the classroom and asking each student to voice his or her own needs, either by creating a rule or agreeing with a rule made by a peer. Connecting with each student’s basic need for safety and respect is a good start. Connecting to children through their behavior is also a way to get to know them better.9 Instead of responding in anger or exasperation to a student who is “acting out,” respond with curiosity. “I noticed that you threw your pen across the room when I corrected your spelling. I’m wondering if you noticed that too, and what you think that’s about?” This neutral, curious, and concerned stance shows the child that you are not judging but want to connect.

The school environment offers a major opportunity for children to develop positive experiences through new social interactions with adults and peers that are in contrast to their own negative models of relationships. Classroom connections for maltreated students are developed through consistent adult responses, helping them to understand the rules that create predictable responses. Peer interactions are the hallmark of school-aged children’s experiences, and classrooms are a natural context within which to help traumatized children make classmate connections.10

Routines and rituals are an antidote to life’s chaos and disruptions, allowing children to shift out of survival mode and into new patterns of adaptive social interactions with adults.11 Rather than reacting to overt behaviors, teachers can model for students how to react to the emotional message behind a student’s behavior. They can help children learn strategies for negotiating interpersonal problems in a supportive context. Research shows that children flourish when they can predict environmental responses and understand the rules for interactions.12

Emotional and Behavioral Regulation

The ability to appropriately manage feelings, emotions, and impulses is impaired by childhood trauma.

13 Emotional arousal can feel scary to a child who has not been taught how to self-soothe and calm down. Imagine you are hearing an alarm go off in your house; it’s loud, dark, and scary, and you cannot find where the noise is coming from to turn it off. In these cases, children need to be taught how to identify and appropriately express emotions. They also require guidance on how to tolerate distressing emotions and calm themselves through self-soothing and self-regulation.

14 In a classroom setting, adults can help children with this essential task in a number of ways:

- Label the emotions you see the children demonstrating. This will give them the language they are lacking. Much like learning the Spanish word for “door,” the children are learning the language of emotions. By labeling the emotion as it is being expressed, the children learn what is going on inside themselves and also are calmed by that knowledge.15

- Place emotion faces with the identifying labels around the classroom. This will help children develop the language of emotion as they learn what sad, happy, confused, and so forth look like.

- Provide an opportunity to reflect on the behavior and feelings exhibited.16 Depending on the developmental stage, this can take the form of a drawing, poem, or essay. Having a quiet space in the school where the child can go to reflect and process what happened and why is a wonderful way to achieve this task.

- Work with the child to calm down. This is also known as co-regulation and is particularly useful with adolescents.17 By focusing on the emotions, not the behaviors, and staying calm while speaking in a soothing voice, the adult identifies the distress and invites the child into a reflective, problem-solving encounter.

- Add calming and mindfulness exercises for all the kids in the class during times of transition. This can be particularly good after a test or a fire/safety drill. These exercises can include listening to breathing, lying on the floor with a stuffed animal on the stomach and watching it move up and down,18 mindfully eating a small piece of chocolate or candy while focusing on the taste and sensations in their bodies, or other activities.

- Use times of emotional dysregulation and distress as an opportunity to educate children about how their brain works and how we can all get overwhelmed by feelings. Neuroscientist Dan Siegel has great videos on his website that explain how the brain works (www.drdansiegel.com). These videos can be shown to individual kids or to the entire class to help them better understand some of the brain science behind behaviors.

Through establishing safety, connection, and emotional and behavioral regulation in schools, the three pillars create the foundation of a trauma-informed structure for children in schools. The more children feel safe and connected to the adults around them, the more they can learn to understand and regulate their emotions and behaviors. This creates a safe learning environment for all children.

Eileen A. Dombo is an associate professor in the National Catholic School of Social Service at the Catholic University of America, where Christine Anlauf Sabatino is the director of the Center for the Advancement of Children, Youth, and Families. This article is excerpted with permission from their book Creating Trauma-Informed Schools: A Guide for School Social Workers and Educators (Oxford University Press). Copyright 2019, Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

*The School Social Work Association of America has taken a stand to stop gun violence in schools with a

position paper on the issue. (

back to article)

Endnotes

1. J. Arvidson et al., “Treatment of Complex Trauma in Young Children: Developmental and Cultural Considerations in Application of the ARC Intervention Model,” Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 4 (2011): 34–51.

2. M. Walkley and T. L. Cox, “Building Trauma-Informed Schools and Communities,” Children & Schools 35, no. 2 (2013): 123–126.

3. I. B. Pickens and N. Tschopp, Trauma-Informed Classrooms (Reno, NV: National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, 2017).

4. G. B. Angell, “Neurolinguistic Programming Theory and Social Work Treatment,” in Social Work Treatment: Interlocking Theoretical Treatment, 6th ed., ed. F. J. Turner (New York: Oxford University Press), 351–375.

5. R. Wolpow et al., The Heart of Learning and Teaching: Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success, 3rd ed. (Olympia, WA: State of Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, 2016).

6. H. Bath, “The Three Pillars of Trauma-Informed Care,” Reclaiming Children and Youth 17, no. 3 (2008): 17–21.

7. Wolpow et al., The Heart of Learning.

8. B. A. van der Kolk, “Developmental Trauma Disorder: Toward a Rational Diagnosis for Children with Complex Trauma Histories,” Psychiatric Annals 35, no. 5 (2005): 401–408.

9. S. E. Craig, Reaching and Teaching Children Who Hurt: Strategies for Your Classroom (Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing, 2008); and K. Souers and P. Hall, Fostering Resilient Learners: Strategies for Creating a Trauma-Sensitive Classroom (Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2016).

10. R. A. Astor and R. Benbenishty, Mapping and Monitoring Bullying and Violence: Building a Safe School Climate (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

11. M. E. Blaustein and K. M. Kinniburgh, Treating Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents: How to Foster Resilience through Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (New York: Guilford Press, 2010).

12. Blaustein and Kinniburgh, Treating Traumatic Stress.

13. K. J. Kinniburgh et al., “Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency: A Comprehensive Intervention Framework for Children with Complex Trauma,” Psychiatric Annals 35, no. 5 (2005): 424–430.

14. Kinniburgh et al., “Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency.”

15. M. D. Lieberman et al., “Subjective Responses to Emotional Stimuli during Labeling, Reappraisal, and Distraction,” Emotion 11, no. 3 (2011): 468–480.

16. Wolpow et al., The Heart of Learning.

17. H. I. Bath, “Calming Together: The Pathway to Self-Control,” Reclaiming Children and Youth 16, no. 4 (2008): 44–46.

18. Wolpow et al., The Heart of Learning.