Civic knowledge and public engagement are at an all-time low. A 2016 survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 26 percent of Americans can name all three branches of government, which was a significant decline from previous years.1 Not surprisingly, public trust in government is at only 18 percent2 and voter participation has reached its lowest point since 1996.3 Without an understanding of the structure of government, our rights and responsibilities, and the different methods of public engagement, civic literacy and voter apathy will continue to plague American democracy. Educators and schools have a unique opportunity and responsibility to ensure that young people become engaged and knowledgeable citizens.

While the 2016 election brought a renewed interest in engagement among youth,4 only 23 percent of eighth-graders performed at or above the proficient level on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) civics exam, and achievement levels have virtually stagnated since 1998.5 In addition, the increased focus on math and reading in K–12 education—while critical to preparing all students for success—has pushed out civics and other important subjects.

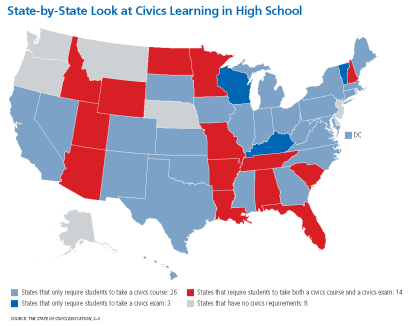

The policy solution that has garnered the most momentum to improve civics in recent years is a standard that requires high school students to pass the U.S. citizenship exam before graduation.6 According to our analysis, 17 states have taken this path.7 Yet, critics of a mandatory civics exam argue that the citizenship test does nothing to measure comprehension of the material8 and creates an additional barrier to high school graduation.9 Other states have adopted civics as a requirement for high school graduation, provided teachers with detailed civics curricula, provided community service as a part of a graduation requirement, and increased the availability of Advanced Placement (AP) United States Government and Politics classes.10

When civics education is taught effectively, it can equip students with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to become informed and engaged citizens. Educators must also remember that civics is not synonymous with history. While increasing history courses and community service requirements are potential steps to augment students’ background knowledge and skill sets, civics is a narrow and instrumental instruction that provides students with the agency to apply these skills. Our recent report on civics education in high schools across the country, The State of Civics Education, from which this article is drawn, finds a wide variation in state requirements and levels of youth engagement. While this research highlights that no state currently provides sufficient and comprehensive civics education, there is reason to be optimistic that high-quality civics education can impact civic behavior.

Key Findings

Here is the current state of high school civics education:*

- Only nine states and the District of Columbia require one year of U.S. government or civics, while 30 states require a half year and the other 11 states have no civics requirement. While federal education policy has focused on improving academic achievement in reading and math, this has come at the expense of a broader curriculum. Most states have dedicated insufficient class time to understanding the basic functions of government.11

- State civics curricula are heavy on knowledge but light on building skills and agency for civic engagement. An examination of standards for civics and U.S. government courses found that 32 states and the District of Columbia provide instruction on American democracy and other systems of government, the history of the Constitution and Bill of Rights, an explanation of mechanisms for public participation, and instruction on state and local voting policies. However, no state has experiential learning or local problem-solving components in its civics requirements.12

- While nearly half the states allow credit for community service, only one requires it.13 Only one state—Maryland—and the District of Columbia require both community service and civics courses for graduation.14

- Nationwide, students score very low on the AP U.S. government exam. The national average AP U.S. government exam score is 2.64 out of 5, which is lower than the average AP score of all but three of the other AP exams offered by schools.15 Most colleges require a score of 3.0 or higher, and some require a score of 4.0 or higher, to qualify for college credit. Only six states had a mean score of 3.0 or above, and no state had a mean score of 4.0 or above, on the AP U.S. government exam.16

- States with the highest rates of youth civic engagement tend to prioritize civics courses and AP U.S. government in their curricula. The 10 states with the highest youth volunteer rates have a civics course requirement for graduation and score higher than average on the AP U.S. government exam. Seven out of the 10 states with the highest youth voter participation rate score higher than average on the AP U.S. government exam.17

Bright Spots in Civics Education

While models for civics education vary widely, innovative programs designed by states, nonprofits, and schools have chosen new ways to promote civics education and increase youth community engagement.

States with rigorous curricula

While most states require only a half year of civics education, Colorado and Idaho have designed detailed curricula that are taught throughout yearlong courses. In fact, Colorado’s only statewide graduation requirement is the satisfactory completion of a civics and government course.18 Because all Colorado high schools must teach one year of civics, teachers are expected to cover the origins of democracy, the structure of American government, methods of public participation, a comparison to foreign governments, and the responsibilities of citizenship. The Colorado Department of Education also provides content, guiding questions, key skills, and vocabulary as guidance for teachers.

In addition, Colorado teachers help civics come alive in the classroom through the Judicially Speaking program, which was started by three local judges to teach students how judges think through civics as they make decisions.19 As a recipient of the 2015 Sandra Day O’Connor Award for the Advancement of Civics Education, the Judicially Speaking program has used interactive exercises and firsthand experience to teach students about the judiciary. With the assistance of more than 100 judges and teachers, the program was integrated into the social studies curriculum statewide. Between the rigorous, yearlong course and the excitement of the Judicially Speaking program, Colorado’s civics education program may contribute to a youth voter participation rate20 and youth volunteerism rate that is slightly higher than the national average.21

Idaho has focused on introducing civics education in its schools at an early age. The state integrates a civics standard into every social studies class from kindergarten through 12th grade. While a formal civics course is not offered until high school, kindergarten students learn to “identify personal traits, such as courage, honesty, and responsibility,” and third-graders learn to “explain how local government officials are chosen, e.g., election, appointment,” according to the Idaho State Department of Education’s social studies standards.22 By the time students reach 12th grade, they are more prepared to learn civics-related topics—such as the electoral process and role of political parties, the methods of public participation, and the rights and responsibilities of citizenship—than students with no prior exposure to a civics curriculum. While Idaho does require a civics exam to graduate from high school, students have already had experience with the material through a mandatory civics course and are permitted to take the test until they pass.23

Nonprofits that support civics education

Generation Citizen is a nonprofit that teaches what it calls “action civics” to more than 30,000 middle school and high school students.24 The courses provide schools with detailed curricula and give students opportunities for real-world engagement as they work to solve community problems. Throughout a semester-long course, the nonprofit implements a civics curriculum based on students’ civic identities and issues they care about, such as gang violence, public transit, or youth employment. The course framework encourages students to think through an issue by researching its root cause, developing an action plan, getting involved in their community through engagement tactics, and presenting their efforts to their class. At the end of the 2016–2017 school year, 90 percent of the students self-reported that they believed they could make a difference in their community.25 With the goal of encouraging long-term civic engagement, Generation Citizen classes combine civics and service learning through a student-centered approach.

Teaching Tolerance, an initiative through the Southern Poverty Law Center, provides free materials to emphasize social justice in existing school curricula. Through the organization’s website, magazine, and films, its framework and classroom resources reach 500,000 educators.26 Because Teaching Tolerance focuses on teaching tolerance “as a basic American value,”27 its materials are rich in civic contexts. The website, for example, provides teachers with student tasks for applying civics in real-world situations and with civics lesson plans on American rights and responsibilities, giving back to the community, and examining historical contexts of justice and inequality. Teaching Tolerance also funds district-level, school-level, and classroom-level projects that engage in youth development and encourage civics in action.

There are many policy levers for advancing civics education in schools, including civics or U.S. government courses, civics curricula closely aligned to state standards, community service requirements, instruction of AP U.S. government, and civics exams. While many states have implemented civics exams or civics courses as graduation requirements, these requirements often are not accompanied by resources to ensure that they are effectively implemented. Few states provide service-learning opportunities or engage students in relevant project-based learning. In addition, few students are sufficiently prepared to pass the AP U.S. government exam.

Moreover, low rates of millennial voter participation and volunteerism indicate that schools have the opportunity to better prepare students to fulfill the responsibilities and privileges of citizenship. While this article calls for increasing opportunities for U.S. government, civics, or service-learning education, these requirements are only as good as how they are taught. Service learning must go beyond an act of service to teach students to systemically address issues in their communities; civics exams must address critical thinking, in addition to comprehension of materials; and civics and government courses should prepare every student with the tools to become engaged and effective citizens.

Sarah Shapiro is a research assistant for K–12 education at the Center for American Progress, where Catherine Brown is the vice president for education policy. This article is excerpted with permission from their 2018 report for the Center for American Progress, The State of Civics Education.

*For more details and state-by-state tables, see the full report. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. Annenberg Public Policy Center, “Americans’ Knowledge of the Branches of Government Is Declining,” September 13, 2016, available at www.annenbergpublicpolicycenter.org/americans-knowledge-of-the-branches….

2. Pew Research Center, “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2017,” May 3, 2017, www.people-press.org/2017/05/03/public-trust-in-government-1958-2017.

3. Gregory Wallace, “Voter Turnout at 20-Year Low in 2016,” CNN, November 30, 2016, www.cnn.com/2016/11/11/politics/popular-vote-turnout-2016/index.html.

4. Sophia Bollag, “Lawmakers across US Move to Include Young People in Voting,” Associated Press, April 16, 2017, www.apnews.com/6be9d9ee28ba49339c35e76e29bd5164.

5. The Nation’s Report Card, “2014 Civics Assessment,” accessed March 20, 2018, www.nationsreportcard.gov/hgc_2014/#civics.

6. Jackie Zubrzycki, “Thirteen States Now Require Grads to Pass Citizenship Test,” Curriculum Matters (blog), Education Week, June 7, 2016, http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/curriculum/2016/06/fourteen_states_now_r….

7. The authors’ calculations are based on data collected from the Education Commission of the States. Data are on file with the authors.

8. Joseph Kahne, “Why Are We Teaching Democracy Like a Game Show?,” Education Week, April 21, 2015, www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/04/22/why-are-we-teaching-democracy-lik….

9. See Angela Pittenger, “Arizona Civics Test May Keep 14 Tucson-Area Teens from Graduating,” Arizona Daily Star, May 21, 2017, www.tucson.com/news/local/education/arizona-civics-test-may-keep-tucson….

10. College Board, “AP Exam Volume Changes (2006–2016),” accessed March 22, 2018, https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/research/2016….

11. The authors’ calculations are based on data collected from state departments of education and the Education Commission of the States. Data are on file with the authors.

12. The authors’ calculations are based on data collected from state departments of education and the Education Commission of the States. Data are on file with the authors.

13. Sarah D. Sparks, “Community Service Requirements Seen to Reduce Volunteering,” Education Week, August 20, 2013, www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2013/08/21/01volunteer_ep.h33.html.

14. The authors’ calculations are based on data collected from state departments of education and the Education Commission of the States. Data are on file with the authors.

15. College Board, “Student Score Distributions: AP Exams—May 2016,” accessed March 22, 2018, https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/research/2016….

16. The authors’ calculations are based on data collected from the College Board. Data are on file with the authors.

17. The authors’ calculations are based on data collected from state departments of education, the Education Commission of the States, the U.S. Census Bureau, the Corporation for National and Community Service, and the College Board. Data are on file with the authors.

18. Colorado Department of Education, “Developing Colorado’s High School Graduation Requirements,” accessed March 22, 2018, www.cde.state.co.us/postsecondary/graduationguidelines.

19. National Center for State Courts, “Colorado Civics Education Program Named Recipient of Sandra Day O’Connor Award for Advancement of Civics Education,” news release, January 12, 2015, www.ncsc.org/Newsroom/News-Releases/2015/Colorado-civics-program-Sandra….

20. See “Reported Voting and Registration, by Age, for States: November 2016,” in U.S. Census Bureau, “Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2016,” May 2017, table 4c, www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/voting-and-registration/p20….

21. See Corporation for National and Community Service, “National Trends and Highlights Overview,” accessed March 22, 2018, www.nationalservice.gov/vcla/national.

22. Idaho Department of Education, Idaho Content Standards: Social Studies (Boise: Idaho Department of Education, 2016), http://sde.idaho.gov/academic/shared/social-studies/ICS-Social-Studies….

23. Clark Corbin, “Districts Adapt to New Civics Test Graduation Requirement,” Idaho Education News, May 4, 2017, www.idahoednews.org/news/districts-adapt-new-civics-test-graduation-req….

24. “Our Story,” Generation Citizen, accessed March 22, 2018, www.generationcitizen.org/about-us/our-story.

25. “By the Numbers,” Generation Citizen, accessed March 22, 2018, www.generationcitizen.org/our-impact/by-the-numbers.

26. “About Teaching Tolerance,” Teaching Tolerance, accessed March 22, 2018, www.tolerance.org/about.

27. Bari Walsh, “Teaching Tolerance Today,” Usable Knowledge, May 17, 2017, www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/17/05/teaching-tolerance-today.