Who could have imagined that, more than 150 years into this bold project of preparing successive generations for informed citizenship, our system of universal education would be as imperiled as it is today? One of the original ideas behind establishing a system of “common schools”—as one of the early advocates for public education, Horace Mann, referred to them—was not that they would all be mediocre, but that children from different backgrounds, the children of workers and the children of factory owners, would be educated together. As Mann wrote in 1848, “Education ... beyond all other devices of human origin, is the great equalizer of the conditions of men—the balance-wheel of the social machinery.”1

Of course, Mann’s own understanding of equality and citizenship was surely limited, as he wrote these words at a time when only white men had the vote, the Emancipation Proclamation was yet to be signed, and the children of workers were more likely to be working in factories themselves than they were to be attending school. And while schools have historically mirrored society’s inequities as much as they have inoculated against them, our public institutions nevertheless have at their foundation the ideals set forth in Mann’s quote and in our most soaring rhetoric about individual freedom and the common good.

And yet, in our current reform climate, our system of public education is often referred to as a “monopoly” rather than a public good. As such, in districts around the country, public schools are being shuttered at an alarming rate, with more than 1,700 schools closed nationwide in 2013 alone.2

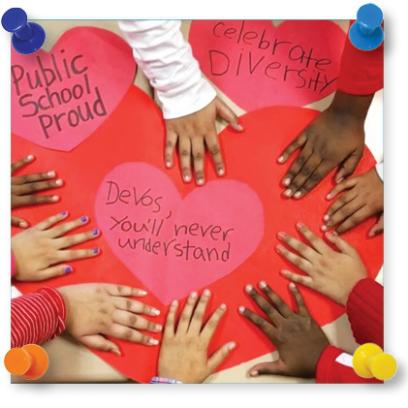

Nowhere is this trend more dramatically played out than in Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’s home state of Michigan, where entire school districts are losing the battle against unregulated privatization through for-profit charter management entities and voucher programs. And while there is no evidence that school choice alone helps to create more equitable educational opportunities, DeVos seems determined to make Michigan a model for the rest of the country.3

With the very existence of our system of free, universal education hanging in the balance, there has not been much of a frame of reference for discussing the need to make our schools more democratic. However, in our recent book, These Schools Belong to You and Me: Why We Can’t Afford to Abandon Our Public Schools, we argue that the threat facing public education is a threat to our democracy writ large. Thus, if we are to take seriously our nation’s founding ideals, schools must remain grounded in the humanistic values underlying the original purpose of a system of education that aims to prepare all comers for competent participation in a country governed of, by, and for the people.

* * *

W. E. B. Du Bois laid claim to this original purpose in 1905 when he declared in a Niagara Movement speech: “When we call for education we mean real education. ... Education is the development of power and ideal. We want our children trained as intelligent human beings should be, and we will fight for all time against any proposal to educate black boys and girls simply as servants and underlings, or simply for the use of other people.”4 All societies educate a ruling class to make important decisions in their own interests, as well as for the society over which they rule. The history of our democracy is defined by the struggle to expand who is part of that ruling class. Du Bois’s quote highlights both the enduring shortcomings of our system of public schooling and the promise it holds out to provide all children—the future stewards of our commonweal*—with a ruling-class education.

There are multiple and complex reasons why, more than a century after Du Bois spoke these words, and nearly two decades after the aggressive and ineffective accountability measures of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), our schools remain as segregated and unequal as ever.5 Certainly one of the primary causes is systemic racism that continues to plague our society. While few schools, regardless of demographics, have ever done a good job at providing children or adults opportunities to engage in experiences with democratic life, in low-income communities of color, schools tend to be characterized by an authoritative school culture. In fact, the level of intellectual and physical freedom in schools tends to correlate directly with the socioeconomic status and skin tone of the student body.6

But another strong factor in perpetuating school inequality is our historic tendency to conflate free-market ideology with democratic ideals. The tension between economic freedom—the right of individuals to enrich themselves—and the need for regulation, social services, and safety nets in the name of creating a strong civic fabric is long-standing in the evolution of our democracy. But over the last several decades, the ideas of free-market thinkers, such as economist Milton Friedman, who wrote the 1995 essay “Public Schools: Make Them Private,”7 have increasingly gained currency, in education reform and beyond.

Within the free-market paradigm, a one-to-one correlation is drawn between what is framed as the “failure” of public schools and what is seen as the “failure” of economically disadvantaged groups to pull themselves up and out of their circumstances. If schools would just teach “those” students more effectively, then, the argument goes, they’d be as likely as their more advantaged peers to compete competently in the pursuit of material wealth and happiness.

But market-oriented reforms prioritize the interests of the already advantaged. This is evidenced in test-based accountability strategies used to leverage school equity, a centerpiece of NCLB. A quick scan of National Assessment of Educational Progress data reveals that white students perpetually do better on standardized tests than all other groups, ensuring their demographically less privileged peers a Sisyphean cycle of catch-up.8 And yet, closing this elusive test-score gap has become a proxy for addressing the very real gaps in privilege. Thus, even as reform rhetoric champions the use of tests and privatization as tools to level the playing field, such tactics actually move us further from that goal.

Although it may seem impractical, even naive, in our current reform climate to advocate for prioritizing democratic education, we argue that such a change in course is imperative if we are ever to get on track toward a more inclusive and, not incidentally, more productive and just society. Our work in democratically governed settings has taught us about the benefits, difficulties, obstacles, and ways forward for creating democratic public schools that prepare the young for engaged citizenship.

It was in working together with colleagues, students, and families that we learned more about the dilemmas a democracy inevitably runs into and how to get comfortable grappling with the inevitable flaws and tradeoffs that arose within the system we created in our school. And through such grappling, we were able to model democratic practices and values for students. In democratic schools, teachers and families discuss, debate, and, as much as possible, make important decisions that affect the school community. Similarly, in such settings, young people have the opportunity to be “apprentice citizens” of their schools, in order to practice becoming active citizens in the larger society.

Ultimately, the purpose of public education in a democracy is to get more Americans, starting in early childhood, to internalize the idea that they are part of the deciding class, as entitled as anyone else to voice an opinion and to make a mark on the world. That, of course, is the ideal—one worth striving for. Given the increasingly precarious state of our public and democratic institutions, it is clear that we are paying a price for not making democratic citizenship an explicit and urgent goal of our national education reform agenda. For how can we hope to educate for democracy if children and the adults in their lives never have the opportunity to observe or practice it? And if such an education doesn’t take place in our public schools, then where will it happen?

Emily Gasoi, a cofounder of the consulting firm Artful Education, teaches in the education, inquiry, and justice program at Georgetown University. She was a founding teacher at Mission Hill School in Boston. Deborah Meier is a former senior scholar at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development and the author of numerous books and articles about public education. A former teacher and principal, she is also a MacArthur Foundation award winner.

*The word commonweal is not often used in writing, let alone common parlance. And yet the meaning, “the common welfare of the public,” should be more familiar, especially in schools, where, we argue, students should be taught to care about the commonweal, their place in it, and what contributions they will make to preserve and improve it. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. Horace Mann, “Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Massachusetts School Board, 1848,” in American Educational Thought: Essays from 1640–1940, 2nd ed., ed. Andrew J. Milson et al. (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2010), 163–175.

2. “Number and Enrollment of Public Elementary and Secondary Schools That Have Closed, by School Level, Type, and Charter Status: Selected Years, 1995–96 through 2013–14,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 216.95.

3. Kevin Carey, “Dismal Voucher Results Surprise Researchers as DeVos Era Begins,” New York Times, February 23, 2017; and Mari Binelli, “The Michigan Experiment,” New York Times Magazine, September 10, 2017.

4. W. E. B. Du Bois, “Niagara Movement Speech,” 1905, TeachingAmericanHistory.org, accessed January 2, 2018, www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/niagara-movement-speech.

5. Gary Orfield et al., “Brown at 62: School Segregation by Race, Poverty and State” (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2016), www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and….

6. Jason P. Nance, “Student Surveillance, Racial Inequalities, and Implicit Racial Bias,” Emory Law Journal 66 (2017): 765–837.

7. Milton Friedman, “Public Schools: Make Them Private,” Washington Post, February 19, 1995.

8. See National Center for Education Statistics, The Nation’s Report Card: Trends in Academic Progress 2012 (Washington, DC: Department of Education, 2013).