In Spring 2017, the mayor of Purvis, Mississippi, sat down with the seventh-graders at Purvis Middle School to discuss the process of making positive changes in their community. This visit was the result of a class project in which students sought to answer the question, “How can we be humanitarians in our community?” Guided by their teacher, Brooke Ann McWilliams, the students conducted research to identify ways to improve their town and wrote proposals based on that research. One girl, as a result of the assignment, applied for a grant to set up and steward a Little Free Library,* a neighborhood book exchange, and garnered city officials’ support for placing it on parkland if she receives funding.

In 2015, as part of a community research project in Columbus, Montana, two of teacher Casey Olsen’s 10th-graders wrote a letter to the editor of the Stillwater County News arguing for the use of Advanced Life Support, an ambulance service provider, to give small communities in their far-flung county access to ambulance services. The letter sparked community conversation and debate, leading to a ballot measure on the issue. On May 3, 2017, Stillwater County voters passed the measure, ensuring the continuation of these services.

Both projects grew out of two accomplished teachers’ participation in the National Writing Project’s (NWP) College, Career, and Community Writers Program (C3WP), which aims to improve young people’s ability to write thoughtful, evidence-based arguments. Formerly known as the College-Ready Writers Program, C3WP builds on the National Writing Project’s 43-year history of cultivating teacher learning and leadership for the purpose of improving the teaching of writing.

A national nonprofit, the NWP facilitates a network of local affiliates throughout the country that support educators in improving the teaching of writing. McWilliams recently completed her first year of C3WP professional development, and Olsen has been a member of C3WP’s national leadership team since its inception in 2013. Their students’ achievements show how engaging professional development prepares educators to lead lessons that teach youth how to not only write evidence-based arguments but also actively engage in civic life.

In an era where public discourse has become increasingly polarized, and “echo chambers” of narrow views populate people’s social media feeds, teaching students to ground their arguments in evidence is more important than ever.† To the detriment of education, we live in what author Deborah Tannen calls the “argument culture,” where “winning” is more valued than “understanding.”1

To equip students to thrive in this challenging environment, the NWP’s approach to argument writing starts with having students understand multiple points of view that go beyond pros and cons and are based on multiple pieces of evidence, which ultimately enables students to take responsible civic action. At its core, C3WP supports students in navigating an increasingly dense informational world so they can become informed citizens who are prepared to participate in and ultimately strengthen a healthy and vibrant democracy.

The NWP’s Approach to Argument: Dialogue, Not Debate

Teaching students to engage in public, civic, and civil arguments requires a focus on using legitimate nonfiction sources in their writing. Readers recognize a thoughtful argument when it’s clear that the writer deeply understands the conversation around the issue, carefully engages a range of viewpoints, and skillfully handles the evidence with commentary that advances the claim. In order to help students and their teachers define and teach the skills associated with using sources, we turn to Joseph Harris’s Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts. Harris understands academic writing as resembling a dialogue more than a debate.2 Participating in a conversation is central to our understanding of argument. Before students develop a solid claim for an argument, they need to get a good sense of what the range of credible voices are saying and what a variety of positions are around the topic. Students have to first distinguish between credible and unreliable sources, and then identify the range of legitimate opinions on a single issue. This initial move counters the argument culture by seeking understanding before taking a stand.

Once students understand a range of perspectives around a topic and develop an initial claim, they begin to select evidence with which to build a case. A virtue of Harris’s book is that he presents the use of evidence in academic writing as a set of possible actions. Writers don’t just plop quotations into their arguments; as his title suggests, they do things. Harris categorizes the rewriting “moves” that writers make into two large categories: forwarding, which advances the argument by using sources to “think with,” and countering, which uses sources “to develop a new line of thinking in response to the limits of other texts.”3 Through understanding and by applying the moves, students are able to “respond to the work of others in a way that is both generous and assertive.”4

How It Works

C3WP is a program for teaching students how to marshal evidence in writing argumentative essays. It includes three interrelated components: professional development, a set of 25 instructional resources for grades 4–12 (most resources describe four to six days of argument instruction), and formative assessment tools. The National Writing Project’s networked structure plays an instrumental role in making C3WP come alive in schools and classrooms.

Many schools, especially in high-poverty areas, are accustomed to professional development providers that materialize for a short period of time, promise success, and then disappear. The NWP, however, relies on well-established local Writing Projects to provide professional development, believing that local teachers are the best teachers of other local teachers. This relationship helps break down resistance to change. As one teacher said, “rather than something that you need to teach, [argument] became something that we can study and talk about together.”

Typically, C3WP provides 45 hours of professional development each year in which teachers undertake the kinds of reading and writing assignments they will later give their students. They also work alongside local Writing Project teacher leaders to develop plans for integrating new teaching and learning approaches into existing curricula. Specifically, during professional development, teachers engage with the C3WP resources as learners and then plan how to use the resources in their own classrooms. This professional development is intensive, embedded, and teacher-to-teacher, with the goal of supporting teachers in learning the underlying principles of the program so they can adapt its instructional resources to their own teaching.

C3WP’s professional development reflects the elements outlined in the Learning Policy Institute’s report on effective professional development.5 It is content-focused on the teaching of argument writing. Local sites create respectful relationships with teachers who then coach and model instructional resources and create occasions for collaborative feedback and reflection. And while professional development generally continues over the course of one school year, in many cases local Writing Project sites form multiyear relationships with partnering schools or districts.

At the latest count, C3WP has been implemented by middle and high school teachers in 41 states—including in rural and urban schools, in places such as Pontiac, Michigan; Gloversville, New York; Los Angeles; and East Tallahatchie, Mississippi—who rely on C3WP’s instructional resources in teaching students how to make evidence-based arguments.6

The C3WP framework rests on what are known as “cycles of instruction” that integrate the program’s three essential components: instructional resources for teaching argument writing, formative assessment tools, and intensive professional development—all developed by teachers for teachers. The NWP makes the interconnections among these components explicit to teachers in the program, and we briefly describe them here.

First, teachers gather as a staff and meet with facilitators from their local Writing Project. They discuss their students and decide on a C3WP instructional resource to introduce argument writing to their classes. Through coaching or model lessons, the Writing Project supports the teachers as they teach the resource and collect the student writing. Teachers then bring the student writing to the next staff gathering. Using one of C3WP’s formative assessment tools, they collaboratively analyze their students’ work and use this information to select the next instructional resource that matches the level of sophistication in their students’ argument writing. This cycle enables classroom instruction, professional development, and formative assessment to build on one another. To implement C3WP, teachers teach a minimum of four cycles, over the course of a year, until it becomes habitual for a school staff to gather and discuss student work and identify the next instructional steps. Students’ capacity for sophisticated argument writing thus builds over the course of an entire year or semester.

Instructional Resources Focused on Nonfiction

Each C3WP instructional resource describes a four- to six-day sequence of instructional activities that focuses on developing a small number of argument skills (e.g., developing a claim, ranking evidence, coming to terms with opposing viewpoints). Ideally, teachers will teach at least four of these resources each year to help students gradually improve their ability to write evidence-based arguments.‡

Every C3WP instructional resource, developed by experienced Writing Project teacher leaders, also reflects six principles (described below) that illustrate the argument for our approach to teaching. The set of instructional materials are based on these principles, which ultimately sustain teachers’ practice.

As teachers engage with these resources in professional development and try them out in their classrooms, they enhance and deepen their understanding of how to teach complex knowledge and skills. We encourage teachers to explore and internalize these principles of effective argument-writing instruction, so they can adapt strategies, seek out texts responsive to student interests and curricular demands, and ultimately design their own instructional units. In this way, C3WP resources serve as generative structures rather than a curricular script to be followed lockstep. Below, we identify each instructional design principle and then illustrate it with an example from the set of instructional resources.

1. Focus on a specific set of skills or practices in argument writing that build over the course of an academic year.

Each C3WP instructional resource focuses on two or three key argument skills, such as organizing evidence in an argument or responding to opposing viewpoints, rather than attempting to teach everything about argument in a single unit. For instance, one resource teachers can use at the beginning of the school year helps students write and revise claims by researching articles on the effects of video games. This resource introduces the practice of making tentative claims that are revisable as students understand and digest new information. After students become adept at developing claims from evidence, the resources support students’ assessment and use of evidence in writing arguments. Each resource adds new argument-writing skills to the students’ repertoire. By the end of the year, students are researching self-selected topics and writing arguments that make change in their communities, as in the vignettes mentioned at the beginning of this article.

2. Provide text sets that represent multiple perspectives on a topic, beyond pro and con.

Most C3WP resources include multiple texts about a single topic, carefully curated by experienced teachers of argument, to support the development of the specific skills emphasized in that instructional resource. Texts are grouped in sets by topic, such as what to do about space junk or police use of excessive force, and present a range of positions, information, modes, genres, and perspectives with which a student can make and support a claim. A text set typically:

- Grows in complexity from easily accessible texts to more difficult;

- Takes into account various positions, perspectives, or angles on a topic;

- Provides a range of accessible reading levels;

- Includes multiple genres (e.g., video, image, written text, infographic, data, interview); and

- Consists of multiple text types, including both informational and argumentative.

3. Describe iterative reading and writing practices that build knowledge about a topic.

C3WP’s “Making Civic Arguments” resource, which guided Olsen’s students in developing op-eds, illustrates this principle with a project-based learning capstone experience. For this cycle, students identify their own topics based on issues that affect their local community and then find their own sources, including surveys of or interviews with local stakeholders, reflecting a range of perspectives on the issue.

After gathering information, students draft detailed research reports, explaining how they conducted their research. Students construct their understanding as they write each part of the report. When carefully analyzing and writing about the evidence they have collected, they sometimes discover that their original position is not as strong as they initially thought. This detailed research report allows them to reflect on their research process and focus on how they unpack the complexity of the issue.

Students return to their detailed research reports as they begin thinking about their op-eds. Students often find that their claims change again as they think through their argument. Through repeated and varied opportunities to investigate, read, and write about their topics, students take more informed positions in their writing.

4. Support the recursive development of claims that emerge and evolve through reading and writing.

To build the habit of mind of forming perspectives based on reasoning and evidence, this principle gets reinforced in every C3WP instructional resource. For example, “Writing and Revising Claims,” an early instructional resource, invites students to practice layering their thinking through reading, reflective writing, and critical thinking as they gather information from texts, consider multiple angles on a topic, develop and revise a claim, and write a full draft. Students write a first reaction to the topic and then experience three layering activities, adding to their initial thinking after each activity.

5. Help intentionally organize and structure students’ writing to advance their arguments.

Organizing vast amounts of information into a cogent, pithy piece of writing is complex for writers of any age—and not easily accomplished by following a single formula. Thus, several C3WP resources present planning tools and strategies for studying high-quality exemplars to support students in mastering the ability to make wise organizational choices. For example, in the “Making the Case in an Op-Ed” resource, students engage in a genre analysis of New York Times “Room for Debate” op-eds. They read several examples, identifying, describing, and explaining the decisions the writers make. And they specifically examine how the writers organize sources in their op-eds.

The goal of this process is for students to see that there is no single “right” way to organize and use evidence in an op-ed. This point is reinforced when students are tasked with planning to write four to six paragraphs by creating a logical order with a purposeful argument, rather than by relying on a predetermined formula.

6. Embed formative assessment opportunities in classroom practice to identify areas of strength and inform next steps for teaching and learning.

Each instructional resource provides guidance about the formative assessment opportunities embedded in classroom instruction. For example, “Making Civic Arguments” highlights the importance of teachers holding writing conferences with students once they list possible topics. This allows teachers to determine whether students have chosen a topic that is researchable and of personal interest. If a majority of students appear to be struggling with this step, teachers can take time to provide additional support in helping students select a topic. If most students have identified productive topics, then the teacher can shift to providing guidance on research strategy for the whole class, while offering more individualized support to students.

As teachers internalize these design principles, adaptations to the resources, such as changes in the text sets to match students’ interests and abilities, become common. In this way, C3WP resources shift from a curriculum to be followed to a set of generative structures from which teachers and students can learn about writing instruction.

The Benefits of Formative Assessment

The primary purpose of C3WP’s formative assessment tools is to support teachers as they plan instruction. Therefore, in addition to formative assessment practices embedded in daily classroom interactions, C3WP engages teachers in collaboratively assessing students’ written arguments to understand what students can already do and what they need to learn next.

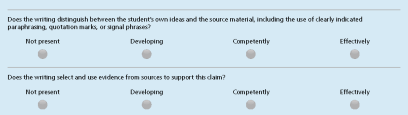

For example, teachers use the C3WP Using Sources Tool during a cycle of instruction to provide a focused look at the quality of students’ claims as well as the selection and use of evidence from sources. This digital tool combines a series of scaled questions related to use of source material and a short narrative question to outline next steps. Its accessible charts and graphs summarize whole-school data, sparking lively and productive conversations among teachers as they collectively identify next teaching steps for their students. The Using Sources Tool focuses on students’ handling of nonfiction sources, specifically on how students introduce and comment on them. This, in turn, helps teachers steer clear of general evaluation and, instead, provide specific information about how students are doing with argument writing. Two questions in the figure below offer a sense of the easy-to-use questions and the focus on sources.

In addition, the Using Sources Tool helps teachers within a school adopt common terminology about argument writing, such as “claim,” “evidence,” “commentary,” “signal phrase,” and “countering.” This language enhances and extends teachers’ assessment of writing beyond a more typical focus on grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. Just as important, the tool also allows students to assess their own writing.

During the initial study of C3WP, teachers saw how beneficial the Using Sources Tool was for them and adapted it for direct use with their students. The Student Using Sources Tool enables student writers to learn from peers and allows teachers to learn from the way students respond to each other. The specificity of their responses, like the focus on formative assessment, is among the student tool’s benefits. Like their teachers, students learn to use language about their texts that is specific to argument writing. As one student says, “I feel like it gave words to things I would have [had] … a difficult time describing.”

Aside from anecdotal evidence that C3WP works, an independent, random-assignment study7 validates the program’s positive impact on both student and teacher learning. Researchers from SRI International evaluated the program’s first iteration in 22 high-poverty, rural districts in 10 states: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Tennessee. They found that students in districts implementing C3WP demonstrated greater proficiency in reasoning and use of evidence in their writing than those in control group districts.

They also found that teachers in participating districts used instructional approaches that differed significantly from those in districts in which teachers did not participate in professional development for C3WP. For example, C3WP teachers were more likely to teach students to connect evidence to claims and to select evidence from source material—key elements of college and career expectations.

Most participating schools and districts, including those in the original evaluation, are underresourced, are under pressure to raise test scores, and often experience high teacher turnover. Despite these challenges, we see success: in the joy teachers get from learning new practices and thinking deeply about writing instruction, in the high-quality student writing that teachers share and celebrate, and in the actual changes in communities spurred by students’ writing.

Linda Friedrich is the director of research and evaluation at the National Writing Project, where Rachel Bear is a senior program associate and Tom Fox is the site development director.

*More on Little Free Library. (back to the article)

†For more on how teachers can help students evaluate digital content so they can reach valid conclusions about social and political issues, see “The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News” in the Fall 2017 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

‡More on C3WP’s instructional resources. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. Deborah Tannen, The Argument Culture: Stopping America’s War of Words (New York: Ballantine Books, 1999).

2. Joseph Harris, Rewriting: How to Do Things with Text, 2nd ed. (Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press, 2017), 37.

3. Harris, Rewriting, 58.

4. Harris, Rewriting, 1.

5. Linda Darling-Hammond, Maria E. Hyler, and Madelyn Gardner, Effective Teacher Professional Development (Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, 2017).

6. The National Writing Project has received funding for the College, Career, and Community Writers Program from the U.S. Department of Education’s Investing in Innovation Fund (i3) and Supporting Effective Educator Development (SEED) programs, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Rural School and Community Trust, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

7. H. Alix Gallagher, Nicole Arshan, and Katrina Woodworth, “Impact of the National Writing Project’s College-Ready Writers Program in High-Need Rural Districts,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 10 (2017): 570–595.