By now, it is pretty much common knowledge that Latinos comprise the nation’s largest minority group, both as a percentage of the population (17.6 percent)1 and as a percentage of school-age students (25 percent).2 That is, one in four K–12 students in the United States is Latino or Latina. While the related challenges are often overemphasized, the tremendous assets these young people bring with them are often overlooked.

In 1980, Latinos were 6.5 percent of the total population and about 8 percent of the K–12 school population,3 and they were principally located in three states: California, New York, and Texas. They did not have a large presence in the rest of the country, where the notion of majority-minority populations was framed in terms of black and white.

The nation’s population has undergone a massive shift in the years since 1980, when immigration began to soar, after historically low rates of Latino immigration between the 1930s and 1970s. The Latino school-age population has tripled since 1980, from 8.1 percent to its current 25 percent.4 The National Center for Education Statistics projects that by 2023, nearly one-third of all students will be Latino.5 However, in three states—California, New Mexico, and Texas—Latinos already account for more than half of all students.

It is important to note that this recent growth is overwhelmingly the result of native births. Contrary to much of the political rhetoric about insecure borders and uncontrolled immigration, more Mexicans have left the country in the last few years than have entered it, and Mexican immigration is now at net zero.6 More than 90 percent of school-age Latino children are born in the United States.7 They are U.S. citizens and our responsibility. How we view these students—primarily as challenges or as assets—will determine to a large extent how we choose to educate them and the kind of success they are able to achieve.

A New Demographic Twist

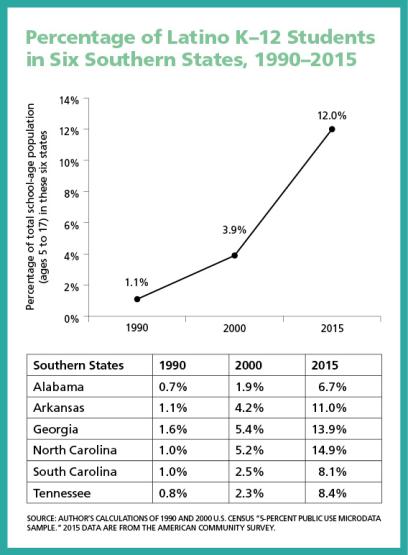

Most Latinos live in what I call seven traditional settlement states: Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, and Texas. However, recently there has been a dramatic shift in where Latinos reside. New pockets of immigration have resulted in concentrations of Latino students in places that haven’t had a substantial number of Latino immigrants before. The Latino population is growing faster in the South than anywhere else in the country. Between 1990 and 2014, the South’s Latino school-age population grew by a factor of 10. Meanwhile, the Latino school-age population grew only 32 percent in the traditional settlement states. Today, Latino children fill classrooms in areas where a generation ago there was no Latino presence.

Not all of these immigrants are Spanish speaking, but the majority of them are. And not all Latinos are from the same country. About two-thirds are of Mexican origin and another nearly 10 percent are of Puerto Rican origin, but the rest come from a variety of Spanish-speaking nations (including Cuba, at 3.7 percent; the Dominican Republic, at 3.2 percent; the Central American nations, combined at 9.1 percent; and South America and elsewhere, at 10.4 percent), and they also come from different social classes and traditions.8 Nonetheless, it is possible to speak of Latinos as one group, since approximately three-quarters are from Mexico and Puerto Rico alone, and these students tend to share many demographic characteristics, such as low educational attainment, high rates of poverty, and a longtime presence in the continental United States.

(click image for larger view)

The Challenges and the Possibilities

As a group, Latinos fall far behind both white and Asian students in academic achievement and educational attainment, largely because they begin school significantly behind their peers; they are the least likely of all subgroups to attend preschool. While Latino children have made significant gains over the last decade, only 52 percent of those ages 3 to 6 attend or have attended a preschool program, compared with an average of 61 percent for all children.9

Moreover, their achievement on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which tests a representative sample of all American students every two years in math and reading, lags behind that of their peers. In 2015, 26 percent of Latino students performed at the proficient level in fourth-grade mathematics, compared with 51 percent of white students and 65 percent of Asian students. In eighth grade, the performance of all students dropped, with 19 percent of Latinos scoring proficient, compared with 13 percent of African American students, 20 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native students, 43 percent of white students, and 61 percent of Asian students.10

Although these results do not differ significantly from the 2013 NAEP results, Latinos have made strides since 2000. Most of those gains happened in the first few years after 2000, after which NAEP scores tended to flatten for all students. It’s no coincidence this stagnation occurred at the same time as the narrowing of the curriculum and the fixation on high-stakes testing began under No Child Left Behind.

With respect to reading in 2015, just 21 percent of Latino students scored at the proficient level in fourth grade, compared with 46 percent of white students and 57 percent of Asian students. In eighth grade, the numbers were similar, with 21 percent of Latino students scoring proficient, compared with 44 percent of white students and 54 percent of Asian students. In sum, achievement gaps between Latino students and their white and Asian peers persist.11

In recent years, Latino students have made progress in high school completion: 76 percent graduated with their class in 2014, compared with 61 percent in 2006.12 Even so, this rate lags far behind graduation rates for white students (87 percent) and Asian students (89 percent).13

The gender gap in Latino high school graduation rates, on the rise since the 1980s, is also troubling, since high school and college completion, or at least some postsecondary training, is a prerequisite for gaining access to the middle class. In 2013, 82.6 percent of Latinas graduated from high school, compared with 74.1 percent of Latino males.14 While 43 percent of white students and 66 percent of Asian students completed at least a bachelor’s degree by age 29 in 2015, only 21 percent of African American students and 16 percent of Latino students did so. Latinas also outperform their male counterparts in college degree completion. In 2015, 18.5 percent of Latinas had earned a bachelor’s degree by age 29, compared with 14.5 percent of Latino males.15

A major reason that Latino college completion is so low is that nearly half of Latinos who attend a postsecondary institution go to two-year colleges, where the likelihood of their transferring to a four-year institution is much lower than for students from most other racial/ethnic groups.16 One study of California community college students with intent to transfer found that only 17 percent of Latinos transferred to a four-year college within seven years, compared with 30 percent of white students and 41 percent of Asian students. These students tend to “get stuck” in community college because they are more likely to work while going to school, to have insufficient funds, and to require remedial courses that delay their progress toward a degree.17 Research shows that Latino students, more than students from any other group, tend to enroll in less selective colleges, even though they actually qualify to attend more selective ones,18 usually because of financial concerns. And notably, more selective institutions tend to graduate all their students at much higher rates.19

Given that income in the United States is closely tied to education,20 our country’s economic and social well-being is tied to the educational success of Latinos. Needless to say, the stakes are indeed high.

Why Latino Students Fall Behind

The underperformance of Latino children has frequently been attributed to the fact that so many grow up in homes and neighborhoods where Spanish is the primary language. In fact, this notion has largely driven language education policy, which has pushed schools to adopt English-only instruction in an effort to reclassify their English learners to English-proficient status as quickly as possible.

Businessman Ron Unz, who spearheaded the English-only movement that began in California in 1998 and traveled as far as Massachusetts by 2002, said that most English learners who received English-only instruction would become proficient in English within a year and would thereafter catch up with their non-Spanish-speaking classmates. Of course, these claims did not come true.21 And earlier studies had routinely found this goal unrealistic.22

The simplistic and misguided explanation that language is the primary impediment to academic achievement overlooks the much more powerful role of poverty. Nearly two-thirds (62 percent) of Latino children live in or near poverty, and less than 20 percent of low-income Latinos live in households where anyone has completed postsecondary education.23 Taken together, these circumstances almost inevitably result in children living in poor areas with few recreational resources and attending underperforming schools where other children like themselves are isolated from mainstream society. As a result, they seldom encounter peers who are knowledgeable about opportunities outside their neighborhoods or who plan to pursue postsecondary education. Additionally, many parents may not have the time or knowledge to evaluate the quality of their children’s education and may not feel empowered to press the schools to strengthen their offerings.

Moreover, these schools are qualitatively weaker in their ability to educate students than the schools that middle-income and white and Asian students attend.24 Sean Reardon, professor at Stanford University, finds that “the difference in the rate at which black, Hispanic, and white students go to school with poor classmates is the best predictor of the racial achievement gap.”25 Still, middle-income black and Latino households are much more likely to live in poor neighborhoods than whites or Asians with the same incomes.26 And racial segregation adds an additional burden to economic segregation, as this double segregation is associated with a social bias against students of color. Latino students are now more segregated than black students across the nation.27

As I noted earlier, this segregation is also associated with linguistic isolation. A linguistically isolated household is defined by the Census Bureau as one in which all household members age 14 and over speak a language other than English and none speaks English “very well.” More than one in four Latino students living in poverty lives in such a home.28 Clearly, it is difficult for Latinos to learn English when they do not hear it spoken at home and they attend school with peers who do not speak English well either. The solution, of course, is not to require parents to speak to their children in English; rather, parents need to help students develop their home language while students are fully integrated into schools and classrooms that expose them to English both formally and informally through peer relationships.*

Research challenges the notion that speaking Spanish is the primary impediment to Latino students’ academic achievement. Several studies29 have now found that immigrant students or the children of immigrants tend to outperform subsequent generations of Latino students academically. Since speaking Spanish is a primary characteristic of Latino immigrants and children of immigrants, this would appear to contradict the idea that language holds them back. Researchers tend to explain this phenomenon as one of motivation.30 The newcomers are acutely aware of the sacrifices their parents have made to come to the United States and often articulate a desire to pay them back by doing well in school. They strive to lift themselves and their parents out of poverty. As a result, they become real believers in the American dream.

However, when this social and economic mobility has failed to materialize after the second generation, and students find themselves trapped in the same low-income settings with few observable prospects, motivation wanes and they develop a negative view of school. Education then comes to represent failure rather than opportunity and threatens their self-worth. As a result, it can make more sense for them to reject school before it rejects them.

The fact that somewhere between a third and a half 31 of all Latino students begin school without being able to speak English certainly has an impact on their achievement. But this impact can be reduced or possibly even eliminated, as part of this problem is of our own making. By making the primary goal moving these students to all-English classes as rapidly as possible, we undermine their acquisition of academic English—the more sophisticated use of language that supports comprehension and literacy.

However, when Latino students are placed in strong bilingual and dual language programs, they outperform their Latino peers in English-only programs and come closest to closing achievement gaps with other students.32 Where such programs are not available, Structured English Immersion programs—where English is the main language of instruction—can provide these students with access to the core curriculum, though it is a matter of debate whether they can provide the same breadth and level of rigor. The best programs build on students’ native language, which ultimately helps accelerate their English skills.

There aren’t as many bilingual programs as there once were, due to several decades of educational policies that promoted a shift to English-only instruction,† but their popularity is again gaining ground.33 In 2016, 73 percent of California voters overturned a 1998 near ban on all bilingual instruction in the state. Commentators attributed this extraordinary turnaround to much more positive attitudes toward immigrants and an explosion of interest in dual language programs, which many feel provide obvious advantages for all children.

Immigration and the Well-Being of Children

While most Latino children in the United States were born here and enjoy the full rights of citizenship, many have at least one parent born outside this country. That means these children often have to deal with the troubled history that can accompany migration—leaving homes and loved ones behind—and can traumatize families.34 Moreover, some members of these families are not citizens and lack legal status. While no exact number is available, best estimates suggest that more than one in four Latino students live with at least one undocumented parent.35 This figure does not account for siblings or other family members at risk of deportation. We can assume that, adding these family members, more than 25 percent of Latino students live in homes stressed by the threat of deportation. Latino students with undocumented parents experience higher levels of poverty, lower levels of educational attainment, and greater dependence on social services than Latino children with U.S.-born parents.36 One can only imagine the psychological toll of sitting in school all day wondering if your parents will be there when you return home.

In 2012, President Obama signed an executive order announcing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), a program meant to defer deportation for certain undocumented immigrants who entered the country when they were younger than 16. A 1982 Supreme Court decision (Plyler v. Doe) declared that undocumented immigrant children had a right to public education through high school, but until DACA began, they could be deported after high school. While DACA did not offer a pathway to citizenship, it did offer a temporary right to be in the country legally for the estimated 65,000 high school graduates who each year complete school but cannot legally work, join the military, or often even continue their education.‡ These young immigrants entered the country with their families, frequently at such young ages they did not even know they were born outside the United States, and certainly had no say in where they were raised.

To be eligible for DACA, immigrants brought to the United States before turning 16 must have lived continuously in this country for at least five years; must have been attending or have graduated from a U.S. high school, or have served in the military; and must not have been convicted of a felony or certain misdemeanors (among other requirements). If they met all the requirements, produced certifying documents, and paid an application fee of $495 (as of December 23, 2016), they may have received deferred deportation and a work permit for a two-year, renewable period. By June 2016, more than 700,000 undocumented people had received a DACA permit.37

While this policy provided considerable relief for many young Latinos, at least half of those estimated to be eligible did not apply. Reasons include fear of the immigration service having information about their families and the high cost of the application, especially in circumstances where more than one individual in the family is eligible. It was also understood that the permit could be revoked at any time, especially under a federal administration that disagrees with the policy. Given the program’s uncertain future under the Trump administration, many students whose DACA terms have expired are returning daily to regular undocumented status without the ability to work legally. Among other challenges, this creates a hardship for paying for higher education.

According to estimates, roughly 500,000 U.S.-citizen youth currently live in Mexico as a result of deportations and economic circumstances that forced their families back across the border.38 These young people, born in the United States, usually have no history with Mexico and most often have been educated only in English. Once in Mexico, they often have trouble integrating into Mexican schools, which have different curricula and standards than American schools and, obviously, require students to speak, read, and write in Spanish. They also often have difficulty convincing Mexican school officials they should receive credit for classes they took in the United States. If the new federal administration makes good on its promises to remove undocumented immigrants, the number of students in this situation can be expected to grow because many U.S.-born children of immigrants will accompany their deported family members.

President Obama attempted to address this problem in 2014 with his Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) policy, which would have allowed parents of citizen children who met a series of requirements to remain in the country with renewable work permits, much like the DACA applicants. This policy would have prevented many of the “returned” students from having to leave the country to an uncertain fate in Mexico. A recent Supreme Court decision resulted in a stay of DAPA, leading many U.S.-citizen children to worry about being removed from the only home they have ever known.

In spite of these enormous challenges, stories of undocumented students who have excelled academically are recounted each year at graduation and in national newspapers.39 Anyone teaching in colleges across the country is likely to encounter these students.

As a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, I have taught many undocumented students. One I will never forget was always early to class, well prepared, and engaged. One day, she asked me if I had an extra copy of a text we were reading for class. She was having difficulty accessing the library’s copy. As we talked, I learned that not only could she not afford to buy books, she could not afford a place to live and slept on friends’ sofas. She was also frequenting a food pantry. She couldn’t legally work because she was undocumented, having been brought to the United States in the third grade. But she was a musician in a Mariachi group, which, when they could get bookings, helped her meet expenses. Andrea had excelled in high school and was admitted to UCLA, one of the most competitive public universities in the country, and she credited her parents’ example of working hard and never giving up. But it was her involvement in extracurricular activities that fueled her hopes for the future:

Music played a very important role because it was a big motivator. … I couldn’t afford books sometimes, I couldn’t afford rent, [but] I always had music to look forward to. It just kept me going so much, even when things got really, really hard. … When I could have given up and I could have just thrown in the towel, I always had music to look forward to.40

Of course, it was not only music that kept Andrea in school and moving toward her goals but also a supportive campus environment, a peer group that sustained her, and faculty members who saw her potential and encouraged her.

Primed for “Deeper Learning” and Bridge Building

Plenty of challenges remain in closing achievement gaps for Latino students. But these students represent enormous assets for our nation. Given that a majority of Latino students are the children of immigrants (and to a much lesser degree immigrants themselves),41 I have outlined five ways these students are primed for “deeper learning,” a pedagogy that has been heralded as fostering the kinds of skills that best serve 21st-century challenges. That is, an emphasis on critical thinking, analysis, cooperative learning, and teamwork. The five characteristics that are typical of many immigrant students are a collaborative orientation to learning, resilience, immigrant optimism, multicultural perspectives, and multilingualism.

Psychologists have long noted Latina mothers’ emphasis on cooperative and respectful family relations that foster a preference for cooperative learning by Latino children.42 Cooperative behavior lends itself to the kinds of shared inquiry and teamwork that are the cornerstones of deeper learning and skills that many employers find crucial.

Because immigrants cannot rely on the normal routines of their homelands and must be adaptable to new circumstances and expectations, children learn to be resilient, to persist in the face of adversity, and to keep trying until “they get it right.” This persistence leads to deeper learning.

Research has also shown that first- and second-generation immigrant students tend to outperform subsequent generations academically, in spite of language differences and cultural barriers. This phenomenon has been labeled “immigrant optimism,” in which these students, taking a cue from their immigrant parents, come to be true believers in the American dream and strive to realize it, exhibiting extraordinary motivation.

Finally, and somewhat obviously, immigrant students typically have multicultural perspectives and are multilingual. These students are both immersed in American culture outside their homes and part of their family’s culture. Being able to view a problem from multiple cultural perspectives allows students to see that problems can have more than one right answer and is key to more creative thinking. And students who speak multiple languages demonstrate greater cognitive flexibility and executive function (for example, ability to maintain a focus when faced with multiple stimuli).43

Also, students who are fluent in another language and culture can build bridges in a fundamentally interconnected world. Knowing another language quite obviously enables access to many more people, information, and experiences. But knowing another culture—understanding how others think and how to present oneself in a different cultural context—is an invaluable skill.

Acknowledging this fact, one recent survey of employers across all sectors of the economy found that two-thirds preferred hiring a bilingual individual over a similarly qualified monolingual.44 Clearly, employers view these multilinguals as assets to building client relationships and managing diversity within a company. As Nelson Mandela said, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, it goes to his heart.” Both business and diplomacy are best served by speaking to a person’s intellect and heart.

Just as students who develop skills in more than one language are advantaged in many ways, so is the education system that understands the value of communicating in multiple languages. By speaking a language the student understands, school personnel help that student—and his or her family—feel more connected to the school and believe his or her teachers care.

What We Know Works

One of the most distressing things about the Latino education gap is that we actually know how to narrow it, and perhaps even close it. We simply do not act on this knowledge. For example, while schools clearly don’t have the power to eradicate poverty, they can use proven strategies to counter its effects, including providing “wraparound” services for students and families living in poverty.§ Significant evidence shows that making social and medical services available to families and students in need helps reduce absenteeism (a major correlate of low achievement) and increase student engagement in school. And while the new federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) provides for the use of such services, the funds available hardly cover the tremendous need that exists.

We also know that preschool works. Early childhood education introduces Latino children to the expectations of schooling and exposes them to English. Based on national data, researchers found that the Latino-white achievement gap narrows by about one-third during the first two years of schooling, but then remains constant over the next several years,45 suggesting that early intervention can be especially effective.

Another bulwark against the effects of poverty is desegregation. In recent years, education reformers have claimed that equity in education could be achieved within racially and economically segregated schools. Yet the desegregation movement of the 1960s and 1970s was supported by research that showed how segregation fueled achievement gaps among racial and ethnic groups.46 In fact, the primary finding in Brown v. Board of Education was that separate could not be equal.

Effective desegregation has become increasingly difficult, as the racial and ethnic composition of the nation’s schools has shifted dramatically. Nonetheless, segregation by class, race, and language can be improved through strong magnet programs and, in the case of Latinos especially, through two-way dual immersion programs.** These programs have a goal of enrolling equal numbers of English speakers and English learners so that both groups become bilingual, biliterate, and culturally aware.

An abundance of evidence suggests the effectiveness of these programs in both raising academic achievement and desegregating students.47 While the demand for these programs is increasing,48 they require strong bilingual personnel. Although there has been scant support for the recruitment and development of teachers to sustain these programs, states can use funds from ESSA to hire more bilingual teachers.

Where two-way programs that enroll both English speakers and English learners are not feasible because of local demographics, bilingual programs that allow Latino English learners to access the regular curriculum in Spanish as they learn English also show strong results for Latino students.49 But they too require bilingual teachers.

Many programs serving low-income students, including Latinos, have as a goal to prepare them for high school graduation and college entrance. The most cost-effective programs include counseling components that guide students into the rigorous courses often denied to them because of the perception they “aren’t college material.” They also usually provide tutorial support. Teachers in these programs inspire students to prepare for college and provide the study skills necessary to succeed.50

One such program is AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination),†† which operates in most states and provides counselors plus a supportive peer group to help students stay on track in school. Another program, known as the Puente Project, operates in California and Texas and targets Latino students (though others can enroll); it provides a college preparatory English curriculum that incorporates Latino literature and integrates aspects of the Latino community into its activities. It also relies on building a supportive “familia” among peers and incorporates program personnel who can communicate with parents. Lastly, PIQE (Parent Institute for Quality Education), which originated in San Diego but now operates throughout California and in 10 other states, focuses on Latino parents, especially immigrants with little knowledge of how U.S. schools operate, and trains them to advocate for their children and monitor their school performance. The program also trains parent coaches to teach other parents; most PIQE programs operate in Spanish.

Research has found that Latino students are the least likely to take on debt for college and the most likely to forgo college (and sometimes even not finish high school) for financial reasons.51 It is especially important for Latinos to access financial assistance, so programs that encourage Latino students to attend college should provide information on how to pay for it. For many Latino students, money for their own education often comes at the cost of basic necessities for other family members. One study conducted in the aftermath of the Great Recession found that 40 percent of Latino students in a very large state university could not rely on their families for any financial support; instead, they were a source of support for their parents and siblings.52

Finally, it is axiomatic that students must feel a sense of belonging in school if they are to be truly engaged and motivated to excel. Relationships are crucial. Somewhat paradoxically, though, Latinos are the least likely to participate in extracurricular activities in school, where many friendships begin.

In a series of studies that looked at the “sense of connectedness” of students of Mexican origin, the researchers concluded that among the most important school interventions for these students is connecting them to extracurricular, out-of-classroom activities in order to bind them to peer groups and to the school. Similarly, researchers have found that those immigrant students “who had even one native English-speaking friend were able to learn English more rapidly and make a better adjustment to school.”53 Another recommendation stemming from these studies was to offer extracurricular activities during the school day, so that all students could participate in something in which they had a particular interest with peers who shared that interest, but that did not involve additional cost or time after school, when they might be expected to help out at home or at work.54

A typical observation about successful interventions for Latino (and all other) youth is that male students make up only about one-third of college access programs.55 And, since it is males who seem to be in the greatest need of support and motivation, the programs often struggle to involve more young men.

Research suggests that a key to addressing this “male problem” is offering programs that are run by or have staff that include charismatic Latino adult males, who appeal to young Latinos and appear to attract and retain them more effectively.56 In addition, male teachers have a significant positive impact on the academic performance of male students.57 Thus, focusing on the recruitment of Latino male teachers, counselors, and program directors may improve outcomes for Latino male students.‡‡ Programs for these young male teachers may need to include some kind of part-time compensated activity, whether it is school based or work based, as they tend to feel a responsibility to be earners, as indicated in surveys of young Latinos.58 In our own research, we have found, based on national data, that Latinas are more likely to attend college if they have Latino teachers (male or female). In fact, the more of these teachers they encounter, the more likely they are to attend college.59 This, of course, suggests that an important intervention for these students would be recruiting more Latino teachers.

In sum, several interventions are available that would help close achievement gaps. Often, they are not implemented because they require either a rethinking of our normal routines or a substantial investment of both time and money. Arguments based on economic studies show it costs more not to implement what we know works—“pay now, or pay more later.” But these arguments have yet to persuade policymakers, who have the ultimate say in giving such interventions a chance.

What We Must Do

Support at the state and federal levels for universal preschool would go a long way toward providing Latino children a strong academic foundation. While it is critical that these children have access to high-quality early childhood education, it is just as important that it be culturally and linguistically appropriate. Underscoring this point, in June 2016, the Obama administration released a policy statement on the need to “foster children’s emerging bilingualism and learning more broadly” within early childhood programs.60

At the federal level, there is great need for more funding for wraparound services or full-service community schools. This can be accomplished without breaking the bank by integrating the resources of the Department of Education with those of the Department of Health and Human Services and its various subdepartments that deal with early childhood education and youth services. While the old Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, which was disbanded in 1979, may have been too unwieldy for the 21st century, reorganizing these departments to provide more funding for wraparound services makes sense.

Additionally, U.S. education policy should reflect the commitment of other industrialized countries to producing a multilingual citizenry. It should incorporate support for what both of the last two U.S. secretaries of education have agreed on: all children in the United States should have access to dual language education, and emerging bilinguals should not have to forgo the advantage of knowing another language in order to learn English and participate fully in their schools. To that end, the federal government must lend a hand in recruiting and supporting the development of bilingual teachers.

Additionally, states and school districts must create pathways for young people to become bilingual teachers. In recent years, we have witnessed the increasing popularity of magnet programs. Why not create magnet programs that seamlessly transition students from high school to college and teacher preparation programs, with special incentives for students who have acquired another language? Today, 22 states and the District of Columbia offer a Seal of Biliteracy [www.sealofbiliteracy.org] on the diplomas of students who graduate from high school with strong literacy skills in two or more languages. These young people are perfect candidates to pursue teaching, and could probably be convinced to do so with full scholarships from state and federal governments.

To ensure that Latino students have the same access to high-quality education that meets college- and career-ready standards, school districts must place a higher value on counselors, especially those who can communicate with and engage parents of Latino students. Too often, when budget cuts require belt tightening, counselors and nurses are among the first to go. This may be penny-wise and pound-foolish in districts that serve many low-income Latino students, who need the guidance of trained professionals to help them enroll in the coursework required for high school graduation and postsecondary education.

A recent policy shift making it easier for students to earn college degrees holds great hope for helping more Latino students. Currently, 22 states allow students to pursue a bachelor’s degree in specific subject areas within their community colleges. In other words, students who attend two-year institutions in these states do not have to transfer to another campus but can continue seamlessly toward their undergraduate degree without leaving the community college campus. Such a program has the potential to enable many more Latino students to complete college degrees. More colleges should take advantage of this opportunity and expand their program offerings, but unfortunately there is little evidence to date that they are moving in this direction.61

And what can teachers do? Teachers can nurture the assets that these students bring to school, such as their optimism and the persistence they have shown in difficult circumstances. Teachers can celebrate the cultural practices that have nourished immigrant communities and recognize the value of students’ bilingual skills. They can ensure that being labeled an English language learner does not limit a student’s access to all the courses and opportunities that English speakers enjoy. They can help Latino students find an extracurricular activity that truly engages them in school. They can be vigilant about creating equal-status relationships in the classroom so that all students feel they have something to contribute. And teachers can help Latino students see themselves as essential to our nation, which has flourished because of its diversity, not in spite of it.

Patricia Gándara is a research professor and codirector of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles, and also chair of the Working Group on Education for the University of California-Mexico Initiative. A fellow of the American Educational Research Association and the National Academy of Education, she has authored and coauthored numerous articles and books on Latinos in education and English language learners, including The Latino Education Crisis: The Consequences of Failed Social Policies, Forbidden Language: English Learners and Restrictive Language Policies, and The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy, and the U.S. Labor Market.

*For more on dual language learning and English language learners, see the Summer 2013 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

†For more on the history of bilingual education and the renewed interest in bilingual programs, see “Bilingual Education” in the Fall 2015 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

‡For more on DACA, see “Undocumented Youth and Barriers to Education” in the Summer 2016 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

§For more on community schools, see the Fall 2015 issue of American Educator, available at www.aft.org/ae/fall2015. (back to the article)

**For more on socioeconomic integration, see “From All Walks of Life” in the Winter 2012–2013 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

††For more on AVID, see “Focusing on the Forgotten” in the Fall 2007 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

‡‡For more on the importance of recruiting Latino male teachers, see “The Need for More Teachers of Color” in the Summer 2015 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. “QuickFacts,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed October 19, 2016, www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00.

2. “Enrollment and Percentage Distribution of Enrollment in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by Race/Ethnicity and Region: Selected Years, Fall 1995 through Fall 2025,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 203.50.

3. “School Enrollment of the Population 3 Years Old and Over, by Level and Control of School, Race, and Hispanic Origin: October 1955 to 2015,” in U.S. Census Bureau, CPS Historical Time Series Tables on School Enrollment, accessed December 13, 2016, table A-1.

4. Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 203.50.

5. “Enrollment and Percentage Distribution of Enrollment in Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by Race/Ethnicity and Level of Education: Fall 1999 through Fall 2025,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 203.60.

6. Ana Gonzales-Barrera, “More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, November 19, 2015, www.pewhispanic.org/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the….

7. David Murphey, Lina Guzman, and Alicia Torres, America’s Hispanic Children: Gaining Ground, Looking Forward (Bethesda, MD: Child Trends, 2014), 5.

8. Renee Stepler and Anna Brown, “Statistical Portrait of Hispanics in the United States,” Pew Research Center, April 19, 2016, www.pewhispanic.org/2016/04/19/statistical-portrait-of-hispanics-in-the…, table 4.

9. Murphey, Guzman, and Torres, America’s Hispanic Children, 16.

10. “National Achievement Level Results,” Mathematics, Nation’s Report Card, accessed December 13, 2016, www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/ #mathematics/acl.

11. “National Achievement Level Results,” Reading, Nation’s Report Card, accessed December 13, 2016, www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#reading/acl.

12. “Averaged Freshmen Graduation Rate (AFGR) by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, State or Jurisdiction, and Year: School Years 2002–03 through 2008–09,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data, accessed August 6, 2016; and “Public High School 4-Year Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rate (ACGR), by Selected Student Characteristics and State: 2010–11 through 2013–14,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 219.46.

13. Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 219.46.

14. “Public High School Averaged Freshman Graduation Rate (AFGR), by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and State or Jurisdiction: 2012–13,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 219.40.

15. “Percentage of Persons 25 to 29 Years Old with Selected Levels of Educational Attainment, by Race/Ethnicity and Sex: Selected Years, 1920 through 2015,” in National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2015, table 104.20.

16. Jens Manuel Krogstad, “5 Facts about Latinos and Education,” Pew Research Center, July 28, 2016, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/28/5-facts-about- latinos-and-education.

17. Patricia Gándara, Elizabeth Alvarado, Anne Driscoll, and Gary Orfield, Building Pathways to Transfer: Community Colleges That Break the Chain of Failure for Students of Color (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2012).

18. National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, Policy Alert: Affordability and Transfer; Critical to Increasing Baccalaureate Degree Completion (San Jose, CA: National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 2011); and Jennifer Ma and Sandy Baum, Trends in Community Colleges: Enrollment, Prices, Student Debt, and Completion (New York: College Board, 2016).

19. Richard Fry, Latino Youth Finishing College: The Role of Selective Pathways (Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center, 2004).

20. Sandy Baum, Jennifer Ma, and Kathleen Payea, Education Pays 2013: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society (New York: College Board, 2013).

21. Patricia Gándara and Megan Hopkins, eds., Forbidden Language: English Learners and Restrictive Language Policies (New York: Teachers College Press, 2010).

22. Kenji Hakuta, Yuko Goto Butler, and Daria Witt, “How Long Does It Take English Learners to Attain Proficiency?” (policy report, University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute, January 2000), http://cmmr.usc.edu/FullText/Hakuta_HOW_LONG_DOES_IT_TAKE.pdf.

23. Elizabeth Wildsmith, Marta Alvira-Hammond, and Lina Guzman, A National Portrait of Hispanic Children in Need (Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, 2016), 2.

24. Gary Orfield and Chungmei Lee, Why Segregation Matters: Poverty and Educational Inequality (Cambridge, MA: Civil Rights Project, 2005); and Sean F. Reardon, Lindsay Fox, and Joseph Townsend, “Neighborhood Income Composition by Household Race and Income, 1990–2009,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 660 (2015): 78–97.

25. Janie Boschma and Ronald Brownstein, “The Concentration of Poverty in American Schools,” The Atlantic, February 29, 2016.

26. Reardon, Fox, and Townsend, “Neighborhood Income Composition”; and Wildsmith, Alvira-Hammond, and Guzman, National Portrait.

27. Gary Orfield and Erica Frankenberg, Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2014).

28. Wildsmith, Alvira-Hammond, and Guzman, National Portrait.

29. Grace Kao and Marta Tienda, “Optimism and Achievement: The Educational Performance of Immigrant Youth,” Social Science Quarterly 76 (1995): 1–19; Carola Suárez-Orozco and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, Transformations: Immigration, Family Life, and Achievement Motivation among Latino Adolescents (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995); and Edward E. Telles and Vilma Ortiz, Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008).

30. Suárez-Orozco and Suárez-Orozco, Transformations; and Kao and Tienda, “Optimism and Achievement.”

31. Estimates are based on the percentage of Latino children who are the children of immigrants and language data available through the California Department of Education. These data are not reported by the states or nationally.

32. Fred Genesee, Kathryn Lindholm-Leary, William Saunders, and Donna Christian, eds., Educating English Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Ilana M. Umansky and Sean F. Reardon, “Reclassification Patterns among Latino English Learner Students in Bilingual, Dual Immersion, and English Immersion Classrooms,” American Educational Research Journal 51 (2014): 879–912; Rachel A. Valentino and Sean F. Reardon, “Effectiveness of Four Instructional Programs Designed to Serve English Learners,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 37 (2015): 612–637; and Jennifer L. Steele, Robert O. Slater, Gema Zamarro, et al., “Effects of Dual-Language Immersion on Students’ Academic Performance” (paper, Social Science Research Network, October 1, 2015), doi:10.2139/ssrn.2693337.

33. Janet Adamy, “Dual-Language Classes for Kids Grow in Popularity,” Wall Street Journal, April 1, 2016; Amaya Garcia, “What the Rising Popularity in Dual Language Programs Could Mean for Dual Language Learners,” New America Foundation, January 16, 2015, www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/duallanguageexpansion; and Margaret Ramirez, “English One Day, Español the Next: Dual-Language Learning Expands with a South Bronx School as a Model,” Hechinger Report, January 25, 2016, www.hechingerreport.org/english-one-day-espanol-the-next-dual-language-….

34. Carola Suárez-Orozco, Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, and Irina Todorova, Learning a New Land: Immigrant Students in American Society (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008).

35. Wyatt Clarke and Lina Guzman, “What Proportion of Hispanic Children Have an Undocumented Parent?” (paper, Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, April 2, 2016).

36. George J. Borjas, “Poverty and Program Participation among Immigrant Children,” The Future of Children 21, no. 1 (2011): 247–266; and Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Young Children (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2011).

37. “Number of I-821D, Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals by Fiscal Year, Quarter, Intake, Biometrics and Case Status: 2012–2016 (March 31),” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed December 14, 2016, www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studi….

38. Mónica Jacobo Suárez, “Migración de retorno y políticas de reintegración al sistema educativo mexicano,” in Perspectivas migratorias IV, ed Carlos Heredia Zubieta (Mexico City: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, 2016).

39. Janell Ross, “What’s Happening to Two Undocumented Texas Valedictorians Says It All about the Immigration Debate,” The Fix (blog), Washington Post, June 12, 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/06/12/whats-happening-to-tw…; and Katie Rogers, “2 Valedictorians in Texas Declare Undocumented Status, and Outrage Ensues,” New York Times, June 10, 2016.

40. Patricia Gándara, Leticia Oseguera, Lindsay Pérez Huber, Angela Locks, Jongyeon Ee, and Daniel Molina, Making Education Work for Latinas in the U.S. (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2013), 46.

41. Murphey, Guzman, and Torres, America’s Hispanic Children.

42. Taylor H. Cox, Sharon A. Lobel, and Poppy Lauretta McLeod, “Effects of Ethnic Group Cultural Differences on Cooperative and Competitive Behavior on a Group Task,” Academy of Management Journal 34 (1991): 827–847; and Birgit Leyendecker and Michael E. Lamb, “Latino Families,” in Parenting and Child Development in “Nontraditional” Families, ed. Michael E. Lamb (Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1999).

43. Ellen Bialystok, Cognitive Complexity and Attentional Control in the Bilingual Mind,” Child Development 70 (1999): 636–644; Ellen Bialystok, “Consequences of Bilingualism for Cognitive Development,” in Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches, ed. Judith F. Kroll and Annette M. B. de Groot (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Reza Kormi-Nouri, Sadegheh Moniri, and Lars-Göran Nilsson, “Episodic and Semantic Memory in Bilingual and Monolingual Children,” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 44 (2003): 47–54.

44. Diana A. Porras, Jongyeon Ee, and Patricia Gándara, “Employer Preferences: Do Bilingual Applicants and Employees Experience and Advantage?,” in The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy and the US Labor Market, ed. Rebecca M. Callahan and Patricia Gándara (Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, 2014), 234–260.

45. Sean F. Reardon and Claudia Galindo, “The Hispanic-White Achievement Gap in Math and Reading in the Elementary Grades,” American Educational Research Journal 46 (2009): 853–891.

46. James S. Coleman, Equality of Educational Opportunity (Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics, 1966); Gary Orfield, Must We Bus? Segregated Schools and National Policy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1978); U.S. Government Accountability Office, K–12 Education: Better Use of Information Could Help Agencies Identify Disparities and Address Racial Discrimination (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, 2016).

47. Fred Genesee and Patricia Gándara, “Bilingual Education Programs: A Cross-National Perspective,” Journal of Social Issues 55 (1999): 665–685; and Steele et al., “Effects of Dual-Language Immersion.”

48. Adamy, “Dual-Language Classes.”

49. Umansky and Reardon, “Reclassification Patterns”; Valentino and Reardon, “Effectiveness of Four Instructional Programs”; and Genesee et al., Educating English Learners.

50. See Patricia Gándara, Paving the Way to Postsecondary Education: K–12 Intervention Programs for Underrepresented Youth (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2001).

51. Krogstad, “5 Facts.”

52. Patricia Gándara and Gary Orfield, Squeezed from All Sides: The CSU Crisis and California’s Future (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2011). See also, Nick Anderson, “For the Poor in the Ivy League, a Full Ride Isn’t Always What They Imagined,” Washington Post, May 16, 2016.

53. Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco, and Todorova, Learning a New Land.

54. Margaret A. Gibson, Patricia Gándara, and Jill Peterson Koyama, School Connections: U.S. Mexican Youth, Peers, and School Achievement (New York: Teachers College Press, 2004).

55. Gándara, Paving the Way.

56. Gándara, Paving the Way; and Tyrone C. Howard, Jonli Tunstall, and Terry K. Flennaugh, eds., Expanding College Access for Urban Youth: What Schools and Colleges Can Do (New York: Teachers College Press, 2016).

57. Thomas S. Dee, “Teachers, Race and Student Achievement in a Randomized Experiment,” NBER Working Paper Series, no. 8432 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2001); and Thomas S. Dee, “Teachers and the Gender Gaps in Student Achievement,” NBER Working Paper Series, no. 11660 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005).

58. Mark Hugo Lopez, “Latinos and Education: Explaining the Attainment Gap,” Pew Research Center, October 7, 2009, www.pewhispanic.org/2009/10/07/latinos-and-education-explaining-the-att….

59. Gándara et al., Making Education Work for Latinas.

60. White House, Office of the Press Secretary, “Fact Sheet: Supporting Dual Language Learners in Early Learning Settings,” news release, June 2, 2016, www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/06/02/fact-sheet-supporting-du….

61. Patricia Gándara and Marcela Cuellar, The Baccalaureate in the California Community College: Current Challenges & Future Prospects (Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project, 2016).

[illustrations by Gaby D’Alessandro]