For Rebecca Hicks, the past two years have been the most promising of her young life. The high school senior participated in job shadowing activities with lawyers and business executives, met with lawmakers in her state capital, toured monuments and museums in our nation’s capital, visited top colleges and universities, and flew on an airplane for the first time.

While such experiences are quite common for middle-class students, they had been unimaginable to Hicks, not for a lack of motivation (she earns straight As) or a limited curiosity about the world (she reads constantly), but because she hails from a place where the aspirations are many yet the opportunities are few: McDowell County, West Virginia.

The Mountain State’s southernmost county, which sits in the heart of Appalachia, has endured hard times. The once-booming coal industry that enabled many residents to provide for their families is no longer booming. A confluence of factors, such as competition from foreign markets and a shift to natural gas and other forms of energy, has contributed to the decline.

As the jobs disappeared, a mass exodus of residents ensued. In the 1960s, when “coal was king,” roughly 125,000 people lived in McDowell; today the population hovers around 20,000.

Those who remain now face innumerable challenges, poverty chief among them. The current median household income in McDowell is $23,607, well below the state median income of $41,576 and less than half of the national median income of $53,657. Nearly 35 percent of the county’s residents live in poverty. In McDowell County Schools, all students receive free breakfast and lunch because such a high percentage of students in each school qualify for them.

Hicks, who is 18, has experienced some of the challenges behind those statistics firsthand. By the time she was 13, both of her parents had died. She lives with her maternal grandparents. Tall and poised, with long brown hair and glasses, she speaks candidly about her background. She says that she, her grandfather, a retired coal miner, and her grandmother, a homemaker, live on $17,000 a year.

Given her financial situation, Hicks knew better than to ask her grandparents to pay for the educational and travel opportunities she wanted to pursue. But through a public-private partnership led by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) called Reconnecting McDowell, she doesn’t have to.

Getting to McDowell County has always been difficult. The mountains are as treacherous as they are majestic, and drivers must navigate steep and curvy two-lane roads. Ultimately, the lack of viable transportation has contributed to the sense of isolation in McDowell, which Hicks describes as “very closed off from the outside world.” However, Reconnecting McDowell is changing that by bringing much-needed resources and services to the county and providing opportunities for Hicks and her peers to connect with the outside world.

Reconnecting McDowell has managed to connect the county to 125 partners (at the latest count), who have given more than $17 million in goods and services. These include digging water lines by the West Virginia AFL-CIO for new home developments, laying fiber optics for Internet access by Shentel Communications, donations of musical instruments from VH1 Save the Music, and donations of books for students from Voya Financial, Verizon, and First Book,* just to name a few.

Among Reconnecting McDowell’s many projects, one called Broader Horizons is directly geared toward students like Hicks. A mentoring program funded by a three-year, $300,000 grant from AT&T, it pairs high school juniors with mentors and pays for academic enrichment trips to Charleston, West Virginia, and to Washington, D.C., a short plane ride away. Hicks calls the program life-changing. “It has given me the opportunity to see the world from a different perspective.”

Another Reconnecting McDowell project specifically aimed at students and families is a community schools initiative.† Southside K–8 School is in the process of becoming the district’s first full-service community school; a health clinic inside the school is set to open by November. And two other schools will begin the process of becoming community schools this coming school year.

Community schools partner with youth organizations, social service agencies, food banks, higher education institutions, health clinics, and businesses to meet the academic and nonacademic needs of students and their families so that teachers are free to teach and students are ready to learn. The movement to establish community schools has flourished for more than a decade now, with such schools located mostly in urban settings.

The community schools initiative figures prominently in Reconnecting McDowell’s efforts to increase student learning, and rightly so. Research shows that community schools can reduce chronic absences due to poor health, decrease disciplinary issues and truancy rates, increase family engagement, expand learning opportunities, and create more stable lives for children at home.

It may seem strange to some that a teachers union would undertake this work. After all, revitalizing a struggling West Virginia county is well beyond the scope of collective bargaining agreements and improving curriculum and instruction.

According to AFT President Randi Weingarten, the union’s engagement makes perfect sense. “The AFT stands at the intersection of two important social movements: creating educational opportunity and advancing economic dignity,” said Weingarten at a press conference announcing the initiative four years ago. “Our goal is to start reconnecting the children and families of McDowell to the opportunities they deserve so they can not only dream their dreams but achieve them.” And “education is the centerpiece of this effort.”

The Power of Partnerships

The idea for targeting resources to McDowell County came from Gayle Manchin, the former first lady of West Virginia. In the fall of 2011, Joe Manchin, now a U.S. senator, was the state’s governor. At the time, his wife was the head of the state board of education. The board had taken over McDowell’s public schools 10 years earlier because of low student achievement. Despite the move, McDowell’s educational outcomes had not improved, which frustrated Gayle and the board.

In September 2011, Gayle met with Weingarten in West Virginia during the union’s “Back to School” tour. Over dinner in the governor’s mansion, she told Weingarten that she was impressed with the union leader’s work around the country and wanted to partner with the AFT to make a difference in the lives of children in McDowell.

Weingarten told Manchin she was willing to work with her, and she encouraged Manchin to find partners willing to join the effort, according to Bob Brown, a project manager of Reconnecting McDowell, who attended the dinner.

Manchin agreed to sign up partners, and Weingarten asked Brown, a West Virginia native and longtime AFT union organizer, to write a report on the challenges confronting McDowell. What he found showed just how difficult life had become for many in the county. The teenage pregnancy rate was the highest in the nation. So was the rate of deaths from prescription drug abuse, which had devastated families and left many addicted parents unable to care for their children. As a result, nearly half of McDowell’s students lived with neither biological parent, and 72 percent lived in a home with no working adult.

Brown also found that academic achievement was the lowest in the state; the same was true for the high school graduation rate. To top it all off, the school district had significant trouble recruiting and retaining teachers.

After reviewing Brown’s report and talking further with Manchin, Weingarten decided that the AFT should get involved. She promised that the union would engage the community to determine what kind of help it needed; it would not mandate change from the top down. To that end, the AFT held a series of town hall meetings in the county before embarking on the effort.

“The one thing everybody in McDowell told us was, ‘Yes, we’ll work with you on this, but don’t you dare come in here and stay six months and then walk away,’ ” Brown recalls. Manchin and the AFT assured people in McDowell they were in it for the long haul.

By December 2011, Manchin had enlisted 40 partners from the business community, the labor movement, and local churches, among other organizations, and the AFT held a press conference formally announcing the Reconnecting McDowell initiative. Although, by that point, Joe Manchin had been elected to the U.S. Senate, Gayle pledged to continue her work on behalf of the county. She would chair Reconnecting McDowell’s board of directors. At the press conference, the new governor, Earl Ray Tomblin, committed himself to the project and to picking up where his predecessor had left off.

To guide its work, the board created seven subcommittees focused on jobs and the economy; transportation and housing; early childhood education; K–12 instruction; health, social and emotional learning, and wraparound services; technology; and college and career readiness. A mix of state, county, and union officials, along with representatives from partner organizations, sit on each subcommittee. Each month, the subcommittees participate in call-ins with the AFT. Twice a year, Reconnecting McDowell partners attend meetings in West Virginia.

Among the project’s early achievements was one that involved technology. As recently as four years ago, many residents were still using dial-up to go online. But a $9 million investment by Shentel Communications wired all 11,000 homes in McDowell for high-speed Internet access. Shentel also partnered with Reconnecting McDowell to offer steep discounts in Internet access (less than $20 each month) for homes in which McDowell County students live.

Another company, Frontier Communications, agreed to significantly increase the bandwidth in the county’s 11 schools. Previously, the bandwidth was so depleted by the schools’ security cameras that it would take teachers and students at least 15 minutes to pull up something online. Just rewiring the schools “was a huge accomplishment to get people into the 21st century,” Brown says.

The creation of a juvenile drug court in April 2012 was another Reconnecting McDowell achievement. Previously, juveniles charged with drug possession were treated as adults. Now, youth with drug problems are provided medical attention and counseling services, without being removed from the school system. According to Brown, every effort is made to focus on treatment, not punishment, and to keep students in school.

And thanks to a partnership with First Book, a national nonprofit dedicated to donating books, overcoming illiteracy, and increasing educational opportunities, children in the county now have greater access to books. Reconnecting McDowell has opened seven family literacy centers in the county’s social service agencies, which are stocked with free books for students to take home.

While such efforts are in their infancy, many believe they have helped the county begin to move in the right direction. Two years ago, the state board of education was so encouraged by the partnerships forged through Reconnecting McDowell and its focus on community schools that it returned the public schools to the locally elected school board. More recently, for the first time in years, an audit by an educational accrediting agency found improvements districtwide and rated the county’s schools “fully compliant” on measures of academic progress.‡

Compared with just a few years ago, the four-year high school graduation rate for the district has increased, from 74 percent in 2010–2011 to 80 percent in 2014–2015, the year for which most recent figures are available. And the dropout rate has decreased, from 4.5 percent in 2010–2011 to 2 percent in 2014–2015.

Brown acknowledges that these improvements, while modest, are still significant. “We’ve seen a downward spiral going on for 25 years,” he says. “To stop the bleeding and turn the corner, it’s quite a huge accomplishment.”

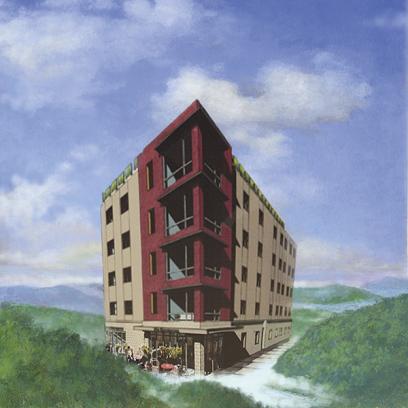

One area that Reconnecting McDowell hopes to include among its achievements is improving teacher recruitment and retention. To that end, it has bought two long-vacant properties (known as the Best Furniture and Katzen buildings) in downtown Welch, McDowell’s county seat, where empty storefronts are the norm, not the exception. The buildings, which once housed a furniture store and a supply company, will be demolished this year to make way for a teacher village set to open by September 2017.

Renaissance Village will be a five-story building of about 30 apartments, most of them one-bedroom units. The building will include stores open to the neighborhood, such as a street-level coffee shop. Brown explains that the housing will attract educators to the hard-to-staff school system. “You can go around the country and find some young, idealistic teacher education grads who would like to give three or four or five years to a place like McDowell because they want to make a difference,” he says. “But they’re not going to go down there and teach if there’s nowhere to live,” or if they have to drive an hour and a half to get to work or have to live in an isolated trailer on top of a mountain, he adds. “That’s why we’re trying to build this.”

The purpose of the village is actually twofold, says Reba Honaker, Welch’s mayor. “It can help with bringing new businesses into town,” she says. “When they see we’ve got an influx of new teachers or new residents, that will encourage them to open.”

For years, Honaker, who once taught in the county’s schools and owned a floral shop in Welch, has seen her city suffer since the coal industry’s decline. The teacher village has given her reason to believe the community can get past the stigma “that there’s nothing here, that everybody’s gone,” she says. “We still have some good kids.”

As if to remind residents of McDowell’s potential, computer-generated renderings of the teacher village hang on the wall of the entrance to City Hall, where Honaker works. The pictures show a modern building with sleek lines, unlike any in the county. In Welch, major construction for new housing hasn’t occurred in decades. But to residents of McDowell, the future building represents more than just much-needed housing for teachers, Honaker says. “It will give everybody hope.”

Finding Solutions through Community Schools

Nelson Spencer understands the challenges of recruiting and retaining teachers. For four years, he has served as the schools superintendent in McDowell. In that time, he has seen many teachers who do not live in the county accept jobs to teach there for a couple of years and then leave as soon as they find work closer to home.

Each year, the district’s roughly 200 teaching positions include about 50 vacancies. At the beginning of this school year, the district was able to fill all but 15 of them—but with teachers not certified in the subject area they are assigned to teach. Another challenge is that most of McDowell’s teachers are novices; nearly 50 percent have less than three years of experience teaching in the county.

The turnover also extends to administrators. Spencer says that before he took the helm, the district had six superintendents in 10 years. The churn, he says, leads to a vicious cycle of training new teachers and administrators each year. The instability also affects the district’s 3,400 students, who can find it difficult to build relationships with teachers who don’t stay in the schools for long.

Spencer is optimistic that Reconnecting McDowell’s focus on education, the economy, and transportation will attract teachers to McDowell. For him, the intersection of all three areas is more than apparent. Better transportation “would be key not only for the school system but for the economy,” he says. To that end, “we want a highway system through McDowell.”

The school system, he says, will continue to play an integral role in Reconnecting McDowell. “It’s not like you’re going to separate what the schools are doing from some outside entity,” says Spencer, who actively participates in the administration of the initiative. He sits on the board of directors, and four of his staff members chair subcommittees.

One particular challenge that Spencer and his staff continue to face is student attendance; districtwide, the average daily attendance rate hovers around 90 percent. Several factors, including health issues, prevent families from being able to send their children to school. For many in McDowell, the nearest doctor is often an hour’s drive away, which means that students commonly miss a full day of school for medical appointments. To reduce such absences, the district plans to transform some schools into community schools.

In the fall, Welch Elementary School and River View High School will start the process of becoming community schools. Meanwhile, Southside K–8 School has already begun its community school transformation.

Southside is located in War, a town best described as a compact little cluster of businesses, churches, and homes at the bottom of a mountain. The mountainsides themselves are far too steep to build on, so buildings line the roads along the mountain hollows.

A little more than a year ago, Southside won a $300,000 state grant for dropout prevention, which it has used for the purpose of becoming a full-service community school. Greg Cruey, the president of AFT McDowell and a middle school math teacher at Southside, wrote the grant. Besides paying for afterschool programs, office equipment for a school-based health center that’s in the works, and additional resources, the grant funded a position for the first full-time community school coordinator in the state. Sarah Muncy, the parent of a Southside student, has held that position for about a year.

Cruey has taught at the school for five of his 12 years in the county. “The challenges that students face are primarily economic,” he says. “Our kids come to school unready to learn.” As an example, he mentions three siblings—a fifth-grader, a fourth-grader, and a first-grader—who live with their grandparents because their mother left them and their father is incarcerated. “Those kids come to school wondering what happens when dad gets out of jail in a couple of months and where they’ll live next and whether or not there’ll be food in the fridge,” he says. “And it’s hard to think about phonics and arithmetic under those conditions.”

By connecting students and families with much-needed supports, Southside can help ensure students come to school ready to learn. One of those supports is a health clinic that the school plans to open this fall. Thanks to a $100,000 grant from the Sisters of St. Joseph, Southside can now afford to renovate one end of its building to house the clinic, which will serve not only its students but the larger community.

The school, however, isn’t waiting until the clinic opens to connect students with services. In the last year, it has partnered with the Smile program, a mobile nonprofit dental group that visits schools throughout the county to provide students with free dental care.

Flo McGuire, Southside’s principal, first heard about the community school model thanks to Reconnecting McDowell, and the idea greatly appealed to her and her staff. So more than a year ago, the school formed a community school steering committee that, McGuire says, has received “a great deal of guidance, resources, and staff development” from the AFT.

McGuire has led the school since 2011. A native of War, she is a 1997 graduate of the town’s now defunct Big Creek High School, which was located behind Southside until it was recently torn down. Big Creek’s gym, a structure built in 1957 that stood yards away from Big Creek’s main building, is still standing, in fairly good condition. It is this building that the steering committee hopes to turn into a community center.

A $100,000 grant from one of the school’s 19 community partners allowed Southside to purchase weightlifting equipment that students can now use in the old Big Creek gym. The school is currently in the process of partnering with a nonprofit group to run the gym as a community center full time and operate programs for residents.

Children in War, like anywhere else, “are going to find something productive to do, or they’re going to find something unproductive,” McGuire says. “Because of our socioeconomic status, because of just a lack of things to do in our town, positive opportunities are not there.” But a community center can offer students options.

McGuire remembers a time not long ago when Big Creek was the hub of the community. “Everything that happened, happened at the high school,” she says. “The idea of the community school is to bring that hub back here to Southside and bring the people back in.”

To some extent, the school is already doing just that with a variety of educational offerings for adults, such as classes in positive parenting, hunter education, and cooking healthy meals, as well as GED courses. Muncy, the community school coordinator, is currently working on partnerships with colleges in the state to offer general education courses at Southside so area residents can pursue higher education closer to home.

Besides finding community partners for the school, Muncy works directly with students, which she considers the most rewarding part of her job. After a fifth-grader recently confided in her that his shoes were too tight, she drove to a sporting goods store an hour away in Bluefield, West Virginia, to buy him a pair that fit. She paid for the shoes with money that a community partner had donated so the school could purchase clothing for students who need it.

Muncy remembers that when she handed him the box, he opened it, then jumped back in surprise. Seeing the smile on his face delighted her. “It was amazing,” she says.

Like McGuire, Muncy graduated from Big Creek High School. In fact, she was one of McGuire’s students when McGuire taught English as a young teacher there. Although McGuire briefly left War for college at Concord University in neighboring Mercer County, she never dreamed of living anyplace else. “I wanted to come back and help,” she says. “There’s so much potential here and so many good people.”

Broadening Students’ Horizons

One Saturday afternoon in March, that potential fills a conference room at the Greenbrier, a five-star resort in West Virginia. Twenty-eight students from Broader Horizons, the mentoring program run by Reconnecting McDowell, have gathered here for a reunion.

The group includes high school juniors currently in the program, as well as college freshmen and high school seniors who are Broader Horizons alumni. The students, whose teachers, guidance counselors, and principals referred them to the program, are here for a one-night stay at the Greenbrier so they can catch up with their mentors and each other. As part of Broader Horizons, their expenses are paid.

At round tables throughout the room, mentors sit with groups of students to discuss study skills, preparing for the ACT, and what life is like in college. Mentors include Reconnecting McDowell’s staff: Bob Brown, the project manager mentioned earlier; Kris Mallory, a project coordinator; Debbie Elmore, a community liaison; and the Rev. Leah Daughtry, the lead project manager of Reconnecting McDowell and the CEO of the 2016 Democratic National Convention. In addition to serving as the liaison to current and potential national partners, Daughtry conceived of and designed the Broader Horizons program and successfully convinced AT&T to sponsor it.

At Daughtry’s table sit graduates of McDowell’s two high schools, River View and Mount View. “So, guys, how is college?” Daughtry says and smiles. Many of them attend Bluefield State College, Concord University, or West Virginia University, among other in-state institutions and a few not too far from West Virginia.

The students tell her they’ve matured a lot during their first year out of high school. Besides making time for schoolwork and part-time jobs (nearly all of them work), several students say they understand the importance of saving money and of changing the oil in their cars. Brandon elicits several laughs by saying you can never get too many alarm clocks. He explains that, at the beginning of the school year, he may have overslept on occasion, but he has learned the importance of being punctual and managing his time.

As Daughtry asks them to share big life lessons they’ve learned, Rayven shifts Jaxn, her 8-month-old baby, on her lap. The young mother is so dedicated to her education—she began at Bluefield State only a week after giving birth—that the mentors allowed her to bring her child, along with her boyfriend, for the weekend.

Daughtry asks her how she manages the baby and college. “It’s not easy,” Rayven says, adding that she usually waits to do her homework until Jaxn falls asleep at night.

A few minutes later, Daughtry asks them to finish this sentence: “I’m proud of myself for …”

“I’m proud of myself for doing something nobody thought I could—having a baby and still going to college,” Rayven says.

“I’m proud of myself for doing everything I told everybody I’d do,” Emily says.

“There’s never a day I’m not tired,” adds Micah, who attends Forsyth Technical Community College in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He then explains just how busy he is. From 8 a.m. to 1 p.m., Monday through Friday, he attends classes. From 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., he studies and does homework. After 5 p.m., he goes to his job and doesn’t get home until midnight. The next day, he wakes at 6 a.m. and does the same thing all over again. Sticking to his schedule takes incredible discipline, he says.

Daughtry sympathizes with him and offers encouragement. “You have to always remind yourself of what good thing happened that day,” she says. “Don’t get hung up on what went wrong. Focus on what you’ve overcome.”

It’s likely that Christian Nealen has heard those words from Daughtry before. The senior at River View High School has experienced his share of tragedy. In the last two years, his stepfather, a coal truck driver, committed suicide, and soon after, his best friend suddenly died. Suffering from depression, he began to skip school and his grades started to drop. But after two months, his mentors in Broader Horizons helped him get back on track.

Nealen, who will attend Concord University in the fall, corresponds with Daughtry on Facebook, checks in with Bob Brown by phone, and often talks to Debbie Elmore in person, since she’s based in McDowell and visits Broader Horizons students at his school. “I realized that I can’t let all the desolation in my life just ruin me and keep me down,” Nealen says. “The only thing stronger than fear is hope. And this program definitely delivers it.”

Visits to places as storied as the Greenbrier, an iconic resort in the Allegheny Mountains, about a two-and-a-half-hour drive from McDowell, have enabled Nealen to see “the other side of life,” as he puts it. Although a friend of his works at the Greenbrier and has shown him pictures, seeing it in person is different—and better. “Just knowing that I walked into the same building that certain celebrities and athletes have come to is amazing,” he says.

But for Nealen, a history buff who hopes to become a civil rights attorney, this visit pales in comparison to the Broader Horizons trip to Washington, D.C. Seeing the White House, the Supreme Court, and the Library of Congress, as well as meeting with his representatives and senators on Capitol Hill, thanks to staff members from the AFT, were among the highlights.

Just as memorable, Nealen says, was the time he was invited to speak at a Reconnecting McDowell meeting to let Randi Weingarten, Gayle Manchin, and the rest of the board know all that the program has done for him. After he gave what he calls a “decent speech,” he received a standing ovation that thrilled him.

“I want these kids to experience every facet” of life, says Superintendent Nelson Spencer, who is grateful for the exposure that such trips have given students. “So now when someone talks about a five-star resort, well, it has a meaning to them.” Spencer acknowledges that while students can read about Washington’s monuments in a book or on a website, walking up the steps of the U.S. Capitol or seeing the expansive White House lawn up close is much more powerful. “The more experiences you have as a human being, the more you can draw from them and make intelligent decisions,” he says.

Such experiences have given Rebecca Hicks the confidence to pursue higher education far from McDowell. In the fall, the senior at River View will attend Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. Hicks received a full scholarship to attend the prestigious liberal arts institution, where she plans to double major in English and economics. One day she hopes to be a novelist and run a nonprofit that helps disadvantaged people become more self-reliant by teaching them to recycle water sustainably. As a resident of McDowell, the need for sustainability has often crossed her mind. “Our natural resources are running out, and, aside from coal, we have nothing to offer to the global world, so we are quickly being forgotten,” she says.

But Hicks is doing her part to counter that trend. She has spent her high school years trying to improve the county’s environment. Through a science enrichment program run by the state, she started McDowell’s first recycling program. Within its first year, the amount of paper the program recycled was the equivalent of 800 trees, she says proudly.

Taking a page from Broader Horizons, Hicks also started a mentoring program at her high school. The program matches seniors with freshmen to help them apply to college, study for the ACT, and prepare to leave River View.

In the six years since her high school opened, Hicks says, not one student has attended college out of state, making her the first. When we talked, she had not yet visited Carleton. But Reconnecting McDowell was working on flying Hicks and her grandparents to see the campus for the first time. She says her grandparents, who have never been on a plane, are excited but apprehensive about her latest adventure. “They’ve rarely left West Virginia, so it’s a big cultural shift for them to start expanding their perspective.”

However, they are grateful for the opportunities that Reconnecting McDowell has afforded her. Bob Brown recalls the time several months ago when Hicks’s grandfather broke down and cried as he thanked him for letting her see the world. Brown, overcome by the outpouring of emotion, simply told him, “That’s what this program is for.”

Jennifer Dubin is the managing editor of American Educator. Previously, she was a journalist with the Chronicle of Higher Education. To read more of her work, visit American Educator’s authors index.

*For more on First Book, see “A Friend in First Book” in the Spring 2015 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

†For more on community schools, see “Where It All Comes Together” and “Cultivating Community Schools” in the Fall 2015 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

‡The full report is available online. (back to the article)

[illustrations by Ken McMillan]