The healthcare industry’s relentless drive toward profit puts patients’ health at risk and has pushed healthcare workers to the breaking point. We see the truth of this every day in AFT members’ faces, and we know that something must be done. Here, we offer an excerpt of the AFT’s Healthcare Staffing Shortage Task Force report that describes the challenges in detail and outlines a path forward. The full report—which includes lessons learned from the pandemic, more detailed research findings (with extensive endnotes), union legislative efforts, and strategic approaches to solving critical problems—is available at go.aft.org/ikt. To hear directly from task force members about addressing the healthcare staffing shortage, listen to the December 12, 2022, episode of the AFT’s podcast, Union Talk.

–EDITORS

Any conversation with a frontline healthcare worker quickly reveals deep frustration and anger with their employers and sheer mental, physical, and emotional exhaustion. The stories from AFT members are heartbreaking: a nurse in Connecticut assigned to 11 patients, a healthcare worker in Oregon who spends 20 minutes before each shift in tears trying to muster the emotional strength to go to work, the nurse in Montana who sees a colleague walking away from bedside care, the healthcare worker in New Jersey grieving the death of a colleague who contracted COVID-19 at the hospital. These are dark days for the healthcare workforce.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a healthcare system woefully unprepared for the crisis, allowing the world to see the chronic understaffing of our nation’s healthcare facilities that existed well before the pandemic. Healthcare employers’ decisions to put revenue ahead of patients and frontline caregivers left the workforce without appropriate personal protective equipment, exposed employees to increasing levels of workplace violence, stretched patient loads to unprecedented and unsafe levels, and left a workforce exhausted and, for far too many, in mental health distress. As a result, frontline caregivers are leaving their jobs in record numbers. America’s hospitals have failed to fulfill their most basic responsibility: providing a safe place for patients to receive medical care.

As one of our nation’s largest unions representing healthcare workers, the AFT and our affiliates have been forced to reckon with dangerously inadequate staffing in our nation’s hospitals and healthcare facilities as well as colleagues who are planning to leave their jobs. Decades of understaffing have reached a crisis point, and it is a crisis of the healthcare industry’s own making.

In response to the crisis of staff willing to endure the working conditions of our nation’s healthcare facilities, delegates to the AFT’s biennial national convention in July 2022 passed a pointed resolution, “Addressing Staffing Shortages in the Healthcare Workforce,” adopting the recommendations made by the Healthcare Staffing Shortage Task Force and, among other things, specifically calling for

- passage of state and federal safe patient levels and securing staffing ratios in collective bargaining agreements;

- banning mandatory overtime;

- passage of federal and state workplace violence protection legislation, including the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act; and

- adequate pandemic preparedness protections in the law through means such as an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) infectious disease standard and updates to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services emergency preparedness rule.

The AFT’s Healthcare Staffing Shortage Task Force Report, from which this article is drawn, demonstrates the union’s ongoing effort to improve our nation’s healthcare system and the working conditions our members endure. It was informed by months of work by the AFT’s Healthcare Program and Policy Council, roundtable discussions between clinicians and policy experts, surveys of healthcare members, and anecdotal discussions and workgroups composed of healthcare union leaders.

Section 1: The Recruitment and Retention Problem

“So many nurses are shorthanded. It’s critical to resupply as people leave the profession.”

—A healthcare worker in Connecticut

Almost universally, AFT leaders are hearing the same thing from frontline workers. Members working in already understaffed facilities are seeing their colleagues leave faster than they can be replaced.

These trends are not only anecdotal. In 2021, the US Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 55,000 fewer RNs employed than in 2020. This was the first decrease in total RN employment in more than five years.

In this same year, the median age of RNs increased for the first time in more than five years; this was driven by a reduction in total employment of RNs under the age of 44. In 2021, there were 100,000 fewer RNs under the age of 44 than in 2020. Looking at the rate of people quitting jobs in the healthcare and social assistance sector over time, we see just how historic this moment is. In 2021, the healthcare and social assistance sector saw its highest quit rate in the last decade.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more healthcare workers have reported that they were considering leaving their jobs or their professions altogether. A healthcare worker in Connecticut links this directly to short staffing, saying, “You can only take care of so many people effectively. This is a recruitment/retention issue. Who’s going to want to go into work when it’s going to be horrible?” In a February 2022 poll, 23 percent of healthcare workers—nearly 1 in 4—said they were likely to leave the healthcare field soon.

The “Great Resignation” comes as the nation’s population ages and grows more diverse, requiring more workers in the health sector. However, in 2021, we see that employers in this sector are only able to hire at about the same rate as workers leave. Yet, we see the rate of job openings continue to increase because of this growing need as the population expands and ages, leaving our healthcare facilities with projected staff shortages.

It Is Time to Improve Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the Workforce Through Targeted Recruitment and Training

As our nation’s hospitals remain understaffed and the demand for healthcare professionals rises, there is an opportunity to make considerable progress toward greater workforce equity, which is a key component of truly centering health equity as the nation’s population continues to diversify. When the healthcare workforce reflects the populations it serves and operates with a deeper cultural sensitivity and understanding of patients’ life situations, patient outcomes improve. This, in turn, increases the comfort level of patients seeking care.

Today, minority healthcare workers are underrepresented, and as the complexity of the positions and the salaries increase, the diversity of the workforce decreases. For instance, while people identifying as Black or African American make up 13 percent of the US population, they make up only 7 percent of nurse practitioners, a higher-paying role requiring more formal education than other nursing roles. This clearly demonstrates a lack of racial equity in the nursing profession, but it also demonstrates an opportunity to “right the ship.”

To create a steady flow of new skilled workers to fill vacant positions, the healthcare pipeline and career pathways must be strengthened. To accomplish this, the sector must conduct targeted outreach, expand stackable credentials (professional credentials that can be lined up sequentially), provide affordable access to the required training programs, and, where possible, accelerate the training process. To maximize the impact of currently uncoordinated healthcare education and training programs nationwide that serve people at various levels of education and training, a nationally coordinated strategy organized around specific projected shortages is required.

One cannot, however, simply pipeline their way out of the current staffing crisis. Until the healthcare sector addresses the deplorable working conditions, dangerous patient levels, and inadequate compensation, it will be unable to attract and train new workers quickly enough to replace those who leave. New approaches must be implemented, and proven training models could be expanded. (Examine the full task force report for seven examples of proven training models that could be expanded, from career and technical education in high schools to nursing residency fellowships.)

Remove Barriers to Entry by Expanding Student Loan and Repayment Programs That Incentivize Joining the Healthcare Sector

A 2019 analysis of data from the US Department of Education found that the average graduate of an associate degree in nursing program held $19,928 in student debt. For graduates with a bachelor of science in nursing, the average debt was $23,711, and for graduates with a master of science in nursing, the average was $47,321.

No effort to recruit talent into the healthcare workforce can be complete until the cost barriers for accessing and completing higher education and training programs are addressed.

While there are no publicly available data on debt burdens or education costs for other healthcare titles, one can make some educated guesses based on the average cost of the level of education required for certain roles. For example, the average cost of an associate degree is $21,900 at a public institution and $57,254 at a private institution. Many healthcare roles, including lab technicians, surgical technologists, radiologic technologists, and respiratory therapists, require an associate degree. Healthcare job titles that do not require a postsecondary degree are also not free of cost barriers because many require certification programs. For example, a program to become a licensed practical nurse can cost as much as $15,000, and training to become a certified nurse assistant averages about $2,000.

The AFT has been leading the effort to make Public Service Loan Forgiveness available for more people working in public service roles. Employees who work full time (30 hours or more a week for eight or more months of the year) for a nonprofit or government employer can qualify for full forgiveness of their federal student loan balance after 120 qualifying payments. This includes most hospital and public health workers. During the Trump administration, this program was woefully mismanaged, with workers’ time credit not being applied correctly and their loan status wrongly placed into default. The AFT successfully sued the Trump administration. Through a yearlong waiver, borrowers who did not previously qualify or who were denied were able to get credit for past payments and get on track for full forgiveness. When properly managed and promoted, and when healthcare professionals and other workers are given the necessary information, the program can be a powerful tool for recruiting and retaining healthcare professionals.

AFT-affiliated unions have been working with state legislatures around the country on targeted strategies that increase the pipeline. This includes the Oregon Nurses Association winning passage of the Nursing Workforce Omnibus Bill (HB 4003) last year, which, among other provisions, creates a nurse internship license to augment the workforce and offers practical experiences for nursing students.

Section 2: Working Conditions Need to Be Improved to Recruit and Retain More Healthcare Workers

“I remember thinking during the first surge, ‘If we just make it through this with none of our members dying, we will be lucky.’ We made it until the third surge when we lost a beloved RN from the OR. We had over 75 percent of our members testing positive at one point during this pandemic. Many members were seriously ill, hospitalized, and some are still recovering with long COVID-19 symptoms. I watched my coworkers develop posttraumatic stress disorder in real time.”

—Sheryl Mount, Health Professionals and Allied Employees, New Jersey

Although there is a growing body of evidence on the patient safety risks associated with poor staffing, much more research is needed on workers’ injuries and illnesses. One of the few studies that looked at the relationship between occupational injuries and staffing found that shifts with fewer nursing care hours, lower RN skill mix, and a lower percentage of experienced staff had higher rates of needlestick injury. The California nurse-to-patient staffing ratio law offers an opportunity to evaluate the impact of staffing on healthcare workers’ health and safety. One study found that registered nurses in California hospitals suffered 55.57 fewer illnesses and injuries per 10,000 RNs, a rate 31.6 percent lower than the rate in all other states. The reduction for licensed practical nurses was 38.2 percent.

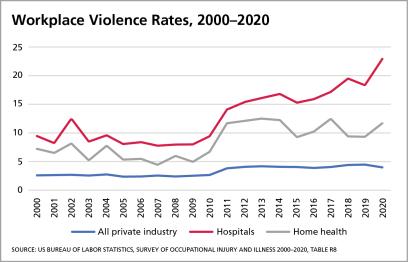

Workplace Violence Makes Hospitals One of the Most Dangerous Places in America to Work, and Enforceable Standards Are Needed to Protect Workers

Violence to healthcare workers is a serious and growing problem exacerbated by inadequate staffing. Healthcare and social services workers experience 76 percent of all reported workplace violence injuries in the American labor force, and the number of actual incidents of workplace violence is likely to be much higher. The rate of reported assaults grew by 144 percent in hospitals and 63 percent in home health agencies from 2000 through 2020. The rate of reported assaults increased by 95 percent in private sector psychiatric hospitals and substance use treatment facilities between 2006 and 2020. There were 87 workplace homicides from 2017 through 2019. Pandemic-related pressures on healthcare accelerated this trend—the rate of violence in hospitals increased by 25 percent in one year alone, from 2019 to 2020.

OSHA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) have both identified understaffing as a risk factor. Long wait times and inadequate attention can lead to escalating behavior in some patients and visitors. In some cases, workers are too busy to notice or respond. When there are too few workers available to safely restrain violent patients or when staff work in isolation, the risk of serious injury increases. More research is needed to investigate a causal relationship between understaffing and workplace violence.

OSHA, NIOSH, and researchers have emphasized the critical importance of workplace violence prevention programs that train frontline staff and managers to report all incidents of workplace violence and “near misses” in order to develop evidence-based prevention strategies. Unfortunately, healthcare workers often do not report incidents of workplace violence because they find themselves blamed for their assault. More work is needed to identify the staffing issues at the root of workplace violence.

click image to enlarge

Fatigue Is Making Healthcare Jobs Unsustainable, and Healthcare Workers Need More Recovery Time

Research on nurse fatigue has focused on the effects of shift work, including extended shifts and overtime, night shifts and rotating shifts, and insufficient recovery time between shifts. Chronic sleep deprivation has been linked to these factors. Chronic sleep deprivation causes fatigue; reduced cognitive function; increased risk of errors, such as needlestick injuries; unsafe driving; and patient safety errors in the short term. Chronic sleep deprivation can cause cardiac, gastrointestinal, and metabolic illnesses in the long run. Chronic lack of sleep has also been shown to foster proinflammatory activity and immunodeficiency, putting workers at higher risk for infection.

AFT local unions have been engaging in innovative bargaining to reduce fatigue among healthcare workers. The Ohio Nurses Association secured “double back” language in its contract with Lima Memorial Hospital, requiring a certain number of hours between shifts. The union also achieved a ban on mandatory overtime at the hospital. The Oregon Nurses Association won double overtime pay for mandatory overtime at Oregon Health & Science University, which puts financial pressure on the hospital to hire more nurses. Meanwhile, the Washington State Nurses Association secured an additional RN float position to ensure adequate coverage, allowing all staff to take meal and rest breaks.

AFT affiliates have been working with their state legislatures to reduce mandatory overtime. The Ohio Nurses Association was successful in passing legislation in 2021 that establishes a legislative study committee on RN staffing issues to help legislators learn more about the issues and build support for better staffing.

Addressing the Mental Health Crisis of Healthcare Workers Requires Funding for New Support Programs

For many years, healthcare workers, particularly those at the bedside, have been stressed and have suffered the moral injury of repeatedly being expected to make choices that transgress their long-standing, deeply held commitment to healing. The scarcity of mental health care providers compounds the mental stress. Those who seek assistance are frequently unable to find providers or are placed on monthslong waiting lists.

A survey conducted in March 2021 by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Washington Post asked healthcare workers whether they felt the worry or stress related to COVID-19 had a negative impact on their mental health. According to the survey, 61 percent said yes. Three out of 10 people polled either received or thought they needed mental health services because of the pandemic. At least 49 percent said the pandemic had negatively impacted their physical health, as well as their relationships with family members (42 percent) and coworkers (41 percent). Many people reported difficulty sleeping, frequent headaches, increased use of alcohol, or drug use, all of which were attributed to pandemic stress and worry. Another recent study found that more than 70 percent of healthcare workers have symptoms of anxiety and depression, 38 percent have symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, and 15 percent have had recent thoughts of suicide. The workforce urgently needs support.

Section 3: Safe Staffing Requirements Are Needed

California is the only state that mandates safe patient levels for multiple hospital departments by law. Massachusetts mandates ratios only for ICUs by law, and New Jersey mandates ratios for several departments through regulation of the hospital licensure process. A number of states also require that healthcare facilities have staffing committees that include nurses. This is based on the idea that every hospital is different, and each should have the flexibility to develop staffing matrices that best fit their departments. Unfortunately, because they are often poorly enforced and lack a clear standard, staffing committees have not proven to be a successful strategy to achieve safe patient limits.

In contrast, safe staffing levels set by law in California have been shown to improve outcomes for patients and healthcare workers. Many experts argue that safe staffing levels are necessary because they provide hospital administrators and workers with a clear measurable standard. Setting the floor in law rather than collective bargaining agreements and staffing plans also allows for enforcement of these standards through state agencies rather than relying on hospitals to monitor their own compliance or on workers to file complaints after a plan has been violated.

AFT-affiliated unions around the country have been trying a variety of strategies at the bargaining table to reduce unsafe patient levels. For example, the Ohio Nurses Association at the Ohio State University Medical Center (OSUMC) won safe patient staffing levels for its workers, including a nurse-patient ratio in the medical-surgical unit of 1:4, while the nurse-patient ratio for the critical care unit in the emergency department is 1:2. The nurses at OSUMC are now empowered to challenge patient care assignments that are unsafe because they exceed the established ratio. While nurses occasionally flex up to accommodate additional patients, it is rare and is only done when the nurse can safely care for all their patients.

AFT-affiliated unions nationwide have also been working with their state legislatures to require increased staffing levels in their facilities and staffing committees. For instance, in New York, our unions won language in their 2019 state budget that requires the Department of Health to study how staffing enhancements and other initiatives can improve patient safety and care.

Outsized Use of Staffing Agencies: A Symptom of the Broken Labor Market That Needs Greater Oversight

With healthcare worker shortages and increasing patient levels during the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals and health systems have begun turning more to healthcare staffing agencies. Though these agencies are not new to the healthcare landscape, rapidly escalating rates and accusations of price gouging have thrust them to the forefront of public debate over the cost of healthcare.

Traveling healthcare workers are a valuable addition to a hospital’s care team in many situations, including bringing workers with specialized skill sets into rural and underserved areas. The problem arises when hospitals and health systems stop investing in recruiting and retaining staff nurses and health professionals and the use of temporary workers becomes a more expensive replacement rather than a supplement.

In a 2022 report, the American Hospital Association evaluated the cost of the pandemic for hospitals, including the increased money spent on temporary workers through staffing agencies. In January 2019, travel nurses accounted for 3.9 percent of total hours worked by nurses in hospitals. In January 2022, they accounted for 23.4 percent. As hospitals have relied more heavily on staffing agency workers, labor costs have skyrocketed. Hospital labor expenses per patient at the end of 2021 were 36.9 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The nurse labor market in our country has been broken. Hospitals have had to scramble to hire nurses in a time of public health emergency because they used lean staffing models prior to the pandemic. Every hospital competing for the same limited pool of nurses at the same time drove up wages. Coupled with years of deteriorating working conditions and lack of fair compensation, many nurses quit their staff nursing position to follow the money, taking traveler positions. Instead of complaining of the high rates charged by staffing agencies, hospitals should accept responsibility for creating a labor market in which dedicated staff are undervalued and underpaid; hospitals should reduce pay disparities and improve working conditions.

Before the pandemic, AFT-affiliated unions had been successfully bargaining language that limited their employers’ use of travel nurses. The Washington State Nurses Association, for example, was successful in having the University of Washington Medical Center declare in their agreement that it “is the intent of the University of Washington Medical Center to minimize the employment of agency nurses.” The Ohio Nurses Association successfully bargained with the Cuyahoga County Board of Health that any “substitute or temporary nurse will not be used to avoid filling any vacancies.” The Oregon Nurses Association successfully got the Sacred Heart Medical Center in Eugene, Oregon, to jointly review the staffing pattern and use of per diem and other nurses in a unit and shift to determine whether additional regular positions/hours should be posted.

Section 4: Compensation of Healthcare Workers Needs to Be Increased

The healthcare industry as a whole was worth a staggering $8.45 trillion in 2018 and accounted for more than 19.7 percent of total US gross domestic product in 2020. The compensation package for people at the top, including hospital executives, reflects this. However, the reality for the people who provide the direct care, provide food for patients, keep the facilities clean and hygienic, and otherwise support the operation of our nation’s healthcare facilities is far different, and they are increasingly discovering that their wages aren’t worth their working conditions.

While hospital CEOs earn an average of $600,000 annually, the true compensation differential at specific facilities can be much greater. For example, in 2018, the CEO of Kaiser Permanente, a large nonprofit healthcare system, made nearly $18 million. In 2017, the top 10 highest-paid nonprofit health system executives earned $7 million or more. Even the bottom 25 percent of nonprofit hospital CEOs enjoyed annual compensation of about $185,000.

In contrast, other healthcare professionals make significantly less, ranging from $125,690 for pharmacists to $38,190 for medical assistants. The gap is only wider for those hospital employees whose jobs do not require specialized degrees, such as janitorial and kitchen staff and medical-records personnel. To successfully recruit and retain staff, the healthcare industry must fix its compensation gap.

Section 5: Corporate Trends

Driven by an insatiable desire for income, hospitals and health systems have systematically undervalued and underinvested in the healthcare workforce. While executives enjoy multimillion-dollar compensation packages, healthcare workers have been forced to do more with less. Lean staffing models that rely upon on-call, mandatory overtime and travel nurses to flex staffing at peak census levels have resulted in dangerous patient loads, which stretched many healthcare workers beyond their limits long before the pandemic.

Following the adage “never let a good crisis go to waste,” the healthcare industry has seized upon the COVID-19 pandemic to advance new cost-saving strategies. One little-noticed provision of the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act gave the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services the authority to waive the requirement that hospitals provide 24-hour nursing services. While this currently applies to only a limited total number of patients, the geographic footprint of these waivers is quite big; 206 hospitals run by 92 systems spanning 34 states have received temporary waivers to run what they call “hospital in the home” and “hospital without walls” programs. These models may foretell the future of care delivery, as evidenced by the 2021 announcement by Kaiser Permanente and the Mayo Clinic of a $100 million investment and joint partnership with at-home acute care company Medically Home. Removing a patient from the hospital setting maximizes profit in the hospital industry by eliminating the need for ancillary services, such as food and environmental services, and 24-hour nursing services.

There is also increased pressure, often driven by the healthcare industry, on scope of practice—essentially, who is allowed to do what. In some instances, expanding scope of practice for a given discipline makes sense, such as allowing a highly trained advanced practice registered nurse to work independently and provide much-needed clinician care in rural America. However, expanding the scope of practice for less-skilled healthcare practitioners only to save money for the employer can impair the quality of treatment provided to patients. These decisions should be driven by increasing access to high-quality healthcare and not from cost considerations as the healthcare industry tries to find new ways to increase revenue.

Rather than trying to solve the staffing crisis, the healthcare industry is looking for ways to deliver cheaper care. To put it bluntly, the industry is sacrificing patient care to save money. Instead of degrading the standard of care, we would all be better served by appropriately staffed healthcare facilities.

Consolidation has been a growing trend in the healthcare sector throughout the 21st century, and the pandemic has only widened the economic gap between the large, prestigious healthcare networks and the remaining community-based hospitals and critical access hospitals, many of which are in rural America. Small, independent hospitals are now financially strapped and ripe for acquisition by larger, prominent systems, which have evolved into regional, multimarket systems. While advocates of consolidation often claim that it will ultimately improve the quality of care, there is no evidence to that effect. There is evidence, however, that consolidation imposes downward pressure on worker pay. Mergers that significantly reduce the number of hospitals in a local labor market have been found to lower wage growth for nurses and other skilled workers. As a result, healthcare positions in those hospitals become less attractive and harder to fill.

Section 6: Worker Voice and Trust

“It gives me hope that nurses haven’t given up yet. Having a union, at least we have a voice.”

—A healthcare worker in New Jersey

As frontline care providers, nurses and health professionals have invaluable insight into how each decision made by hospital administration impacts patient care. This expertise coupled with the trusted position healthcare workers hold in their communities should make it obvious to healthcare employers that healthcare workers are their greatest asset. Yet, too often health systems treat healthcare workers only as an expense to be controlled. When employers treat healthcare workers like disposable parts and not dedicated professionals, it is no surprise that workers experience burnout, hospitals experience turnover, and ultimately, patient care suffers.

A 2019 meta-analysis of the association between nurse work environments and outcomes found that in hospitals with better nurse work environments, the odds of an adverse event or death were 8 percent lower. It is not surprising then that research has also linked nurse involvement in meaningful shared governance with patient satisfaction. The percentage of patients reporting they would definitely recommend the hospital was 14 points higher in hospitals where nurses were categorized as “most engaged” in shared governance based on an assessment of three measures in the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index, according to a 2016 study. The same study found that nurses in hospitals where staff were most engaged in shared governance were 44 percent less likely to report that the overall quality of care was fair or poor and 48 percent less likely to report a lack of confidence that hospital management will resolve problems related to patient care.

The best way to ensure a specific employer’s shared governance is to make it part of a collective bargaining process that holds management accountable for including the perspective of direct care providers. The most successful model is the national partnership between the Kaiser Permanente systems and the AFT’s Oregon Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals and its other bargaining partners. Kaiser’s shared governance is far from a panacea for all that ails the healthcare system, but it has proven to shape management decisions in a positive way, albeit not with complete employee satisfaction.

A collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is the single most potent tool to ensure that healthcare professionals have a protected voice at their facility. CBAs create an accountable system where real discussion between labor and management takes place, giving workers more protection to speak up about difficulties. AFT-affiliated unions, like the Oregon Nurses Association, have successfully bargained for meaningful hospital committees. This includes at Providence St. Vincent Medical Center, where the union successfully bargained for clinical unit self-scheduling, and at Oregon Health & Science University, where the union successfully bargained for unit-based nursing practices committees.

The staffing crisis in our nation’s healthcare facilities is not some mysterious, intractable problem that we lack the tools to fix. Rather, given all that the nation’s healthcare workforce endured through the pandemic and before, it is completely understandable—and with a commitment from healthcare employers to put patients and their workforce above maximizing revenue, it is correctable. The task force’s report includes a menu of strategies that can be used to improve our nation’s healthcare facilities and concrete examples of where they have been successfully used. It is intended to help frame the national discussion about the staffing crisis and to provide a road map to fixing the chronic problem.

[Photos: Nathan Howard / Stringer / Getty Images North America; OFNHP via Twitter; AFT; ONA via Instagram; AP Photo / Gerald Herbert; WSNA via Instagram]