Last February, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers (PFT) and the School District of Philadelphia announced a new paraprofessional career development program. With over $4 million in funding, the program offers several new tuition-free pathways for paraprofessional educators in Philadelphia to become certified classroom teachers. PFT President Jerry Jordan called the program a “historic step towards equity and justice,” noting, “the majority of paraprofessionals in our district are Black and brown women, and it should be lost on no one that they are some of the lowest paid workers in the system.”1 Jordan added that “teacher diversity is sorely lacking” in the district, as demonstrated by a report that showed Philadelphia currently employs 1,200 fewer Black teachers than it did two decades ago.2

Across the country, paraprofessionals in cities are primarily Black and Latina women, and they are far more likely than teachers to live in the district and even the school zone where they work. As for teachers, a 2015 Albert Shanker Institute study showed that the percentages of Black teachers in major city school districts across the nation have declined, sometimes drastically, while the percentages of census-designated Hispanic teachers have broadly held constant.3 At the same time, many of these districts have served a majority of Black and Latinx students since the 1960s, when educators, policymakers, and teachers unions first began building and fighting for para-to-teacher pathways.

This is a strategy with a long history and tremendous potential for developing a more diverse teacher corps and connecting teachers and their unions with the communities they serve. Perhaps most importantly, paraprofessionals have long sought opportunities to become teachers. Teaching jobs have offered paths to economic stability to working people for over a century, but beyond the economics, paraprofessionals are already educators. They have intimate, firsthand knowledge of what makes a classroom successful and every reason to believe they could succeed as teachers. This is why Philadelphia’s program is one of several that AFT locals have fought for and won in recent years, including new or expanded programs in Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh.4

I am a historian of paraprofessional jobs and organizing during the formative years of the 1960s and 1970s. In those years, AFT organizers and their allies spoke of a “paraprofessional movement” that would seize upon the massive demand for these workers—half a million paraprofessionals were hired across the United States from 1965 to 1975—to make public education and paths to teaching more open, diverse, and democratic. That paraprofessionals would make excellent teachers was a core belief of the policymakers, civil rights activists, and teacher unionists who organized to create programs of local hiring and advancement. The promise of a “career ladder” was why many paraprofessionals—then as now, primarily working-class Black and Latina women—applied for these jobs. When training did not materialize, the struggle for opportunities was a key reason paraprofessionals organized with AFT locals in the late 1960s and the 1970s. By 1975, pipeline programs had been established through AFT advocacy and bargaining in cities across the nation.

So, why don’t we have robust para-to-teacher programs throughout the United States today? The quick answer is the crises of the 1970s. Myriad external pressures in the latter half of that decade—municipal fiscal crises that spawned devastating austerity budgets, waning federal support for antipoverty programs, and a conservative turn in US politics—undermined public schools, public sector bargaining, and the public universities that provided teacher training for paraprofessionals. As the first para-to-teacher programs collapsed in the late 1970s, critical assessments of their structures and underlying assumptions emerged. These came both from the paraprofessionals who experienced them and, later, from scholars studying them. Both groups focused on two core issues.

First, even under favorable conditions, only a small percentage of paraprofessionals became classroom teachers. Focusing on this percentage vastly understates the impact of para-to-teacher pipelines. However, it does raise questions for paraprofessionals and their unions about the meaning and impact of pipeline programs in relation to the needs of all paraprofessionals. Then as now, paraprofessionals regularly fought for living wages and basic equipment at work, and some wondered whether career ladders were the best use of union power and resources.

Second, paras and researchers questioned how career ladder programs shaped, and were shaped by, the relationship between paraprofessionals and teachers. The rhetoric and organization of early training programs ranged widely. Some programs asserted shared interests and partner status between paraprofessionals and teachers as a precondition for building these pipelines, while others affirmed a professional hierarchy in which paraprofessionals were not yet worthy of the same respect and voice that teachers enjoyed in schools and unions.

As we (re)build para-to-teacher pipelines, this history has much to offer. There is a strong case for their revitalization, one that the AFT and its locals should celebrate. The challenges and critiques of the 1970s are equally essential. They can help us envision paths for advancement that are not steep, narrow, and hierarchical, but wide, welcoming, and empowering.

The Fight for Advancement

To understand the drive to create para-to-teacher pathways, it helps to start with the origins of paraprofessional jobs amid the post–World War II baby boom. As the US school-going population nearly doubled between 1949 and 1969, demand for educators exploded. Much as in our own time, administrators and politicians scrambled for quick fixes: suspending licensure requirements, running schools on double sessions, and deploying new technologies to reach more students. For their part, teachers and their unions argued that higher wages and better working conditions would best attract more teachers.

One solution advanced by the Ford Foundation caught on because it promised both to staff classrooms quickly and to improve teachers’ working conditions: hiring “teacher aides.” As imagined by Ford, mothers picked for their “natural” nurturing abilities would be paid a pittance to help manage overcrowded classrooms and do “non-teaching chores,” including paperwork and maintenance. Ford ran a pilot program in Bay City, Michigan, from 1952 to 1957 that drew national attention and inspired the hiring of aides around the country.5 According to a 1955 newspaper article, “more than half the ‘aides’ want[ed] to become regular teachers.”6 Writing from Bay City in 1956, Lucille Carroll, a past president of the National Education Association (NEA) Department of Classroom Teachers, saw their potential, noting that “the teacher aide program could be regarded as a long-range recruitment plan.”7 It would take 15 years for this idea to become a union-driven reality, but the spark was there from the start.

Skeptical at first, leaders in both the NEA and AFT soon embraced aide hiring, provided that school districts included clear language to keep aides from replacing teachers. The New York City Teachers Guild, a forerunner of the United Federation of Teachers (UFT, AFT Local 2), petitioned the city to hire teacher aides in 1955, and other locals soon followed. Provisions to provide aides to classroom teachers appeared in both the UFT’s and the Chicago Teachers Union’s (CTU, AFT Local 1) first contracts in 1962 and 1967, respectively.8

Ford made no plan to advance teacher aides, and neither did administrators who hired them. However, in the early 1960s, civil rights activists, policy scholars, and teacher unionists in New York City began to articulate an expanded vision for aide work to meet the needs of children in urban schools.9 In 1963, Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited (HARYOU), an antipoverty organization funded by the Kennedy administration, partnered with Harlem teacher and AFT Vice President Richard Parrish. They launched a program that hired 400 “especially trained” aides to work alongside 200 teachers serving 2,800 students in afterschool programs.10

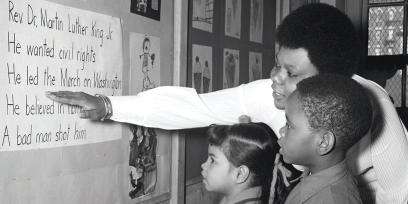

These aides assisted teachers, just as in Bay City, but they also took on new roles. They brought local knowledge—and, in many cases, languages—into their work with students, and they shared key information about school policies with parents. Parrish believed hiring local residents as educators would help students “identify and associate with adequate role models on a more personal level,” and he hoped to develop paths for the aides to become teachers.11

The following year, HARYOU published a report that called for “parent aides” with expanded roles—distinct from the aides already at work—to be hired in public schools.12 “It is HARYOU’s belief,” the report read, “that the use of persons only ‘one step removed’ from the client will improve the giving of service as well as provide useful and meaningful employment for Harlem’s residents.”13 Their timing was excellent: President Lyndon Johnson had just declared the “War on Poverty” and empowered his administrators to focus on community action. Organizers and scholars—including Frank Riessman, a New York University professor who worked closely with HARYOU—moved quickly to shape the legislation that followed.

In 1965, Riessman published a book with Arthur Pearl of the University of Oregon titled New Careers for the Poor: The Nonprofessional in Human Service.14 Pearl and Riessman argued that hiring “Indigenous nonprofessionals” (HARYOU’s term, which they cited) in education, healthcare, and social work would have a triple effect: improving service delivery, forging links between institutions and those they served, and creating jobs that would diversify the human service workforce. In addition to this massive program of hiring, Riessman and Pearl argued for the creation of career ladders that would train aides to become fully licensed teachers, nurses, and social workers. The book caught the attention of Congress and the Johnson administration, which wrote provisions for the hiring and training of aides into legislation and program guidelines.15 In these policy documents, “paraprofessional” began to replace “aide,” suggesting the possibility of future professional status.

At this juncture, AFT leaders moved from bargaining for aides to organizing with paraprofessionals. In 1964, UFT President Albert Shanker had replied to a letter from school aides seeking to unionize by referring them to District Council 37 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME).16 By 1966, Shanker had joined civil rights activists and policy scholars in pushing the New York City Board of Education to hire paraprofessionals, and he asserted that the UFT would seek to organize these “pedagogical employees.”17 New York City hired its first paraprofessional educators in 1967, explaining that these new programs would “improve communications with communities, improve instruction in the kindergartens, and provide opportunities for residents in disadvantaged communities, who possess the ability, to develop into teachers” [emphasis added].18 Opportunities for training, however, remained limited until paraprofessionals organized to secure them.

When the UFT launched its campaign to unionize paras in January 1968, organizers quickly learned that many paraprofessionals hoped to become teachers. Reporting on a survey of 230 paraprofessionals and 200 teachers conducted in May 1968, field organizer Gladys Roth made paraprofessionals’ desire for advancement a central theme. She quoted three representative paraprofessionals: one said, “I always wanted to go back to school; now I can”; another felt “income while learning” was “marvelous for low-income families”; and a third called career advancement the “opportunity of a lifetime.”19 However, the survey indicated that programs of training were difficult to access, and Roth noted that her organizing work regularly included “requests from classroom teachers to provide service for their assistants who were not paid promptly or who were closed out of community college courses.”20 The solution was clear: as one para explained, “We need a union to help get better things for us.”21

Roth’s report was overshadowed by the escalating conflict between the UFT and the community-controlled school district in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Brooklyn. While the initial fight was about due process—the district’s governing board had unilaterally dismissed 19 teachers (forcing them to transfer to different schools), in violation of the UFT’s contract—the substantive issue behind these transfers was the question of what made a successful teacher. The UFT argued that the transferred educators had certifications, experience, and tenure that demonstrated their competence, while the Ocean Hill-Brownsville governing board argued that the teachers’ insufficient investment in the predominantly Black and Puerto Rican community, and its experiment in school governance, rendered them unfit to teach. Unable to resolve the conflict—and with the city’s political leaders abdicating responsibility for adjudicating the issue—the UFT called three successive strikes in the fall of 1968.22

There is far more to say about paraprofessional educators’ experience of this citywide conflict, but suffice to say that they found themselves in the middle of the maelstrom. Some crossed picket lines at the request of community organizations, while others stayed out in solidarity with teachers. Paraprofessionals had been hired from surrounding neighborhoods to better connect schools with communities, which some believed validated the governing board’s position. However, many also hoped to become certified teachers and stood with the union.

As for teachers, while Roth’s report had shown teacher support for paraprofessionals, letters to the UFT offices, as well as paraprofessionals’ own remembrances, revealed that other teachers feared and opposed the presence of paraprofessionals in their classrooms.23 Some believed paraprofessionals would act as spies or agitators in schools. The strike—and the willingness of some paraprofessionals to cross picket lines—confirmed their fears.

Other teachers felt the presence of paraprofessionals threatened their own hard-won professionalism. Even before the strike, one Lower East Side teacher wrote to complain both of paraprofessional hiring and of proposed teacher training, claiming that the process subverted “open, competitive examinations.”24 As the question of teacher competence—what defined it and who got to decide—became a central issue during the 1968 strikes, there was no guarantee that teachers would support an alternative training pathway for community-based paraprofessionals.

After the strikes, Albert Shanker recruited Velma Murphy Hill, an experienced civil rights organizer, to revive the paraprofessional campaign. Hill met with paraprofessionals all over the city who regularly told her of their desire to become teachers. In union materials throughout the campaign, the UFT asserted that the “school union” could guarantee these paths to teaching.25 When nearly 4,000 New York City paraprofessional educators went to the polls in June 1969, they chose the UFT over AFSCME District Council 37. The UFT then spent a year organizing to bring the city to the bargaining table, with Shanker conducting “one of the most intensive internal education campaigns”26 in the local’s history to convince teachers to support paraprofessionals; Shanker famously threatened to resign if they did not.27 Teachers eventually voted to support a paraprofessional strike in June 1970.

While UFT organizers pounded pavement in New York City, AFT President David Selden exchanged letters with Frank Riessman. Their correspondence would help to shape both the UFT and the overall AFT approach to paraprofessional unionism, with career training for paraprofessionals at the center of the process. Selden had written to Riessman in 1968 to say he favored the hiring of paraprofessionals and “the development of career lines which would permit such personnel to advance ... until teacher status has been achieved.”28 He also shared his concerns that teachers might oppose the use of union resources to develop these career ladders.

In February 1969, Selden thanked Riessman for making “a very cogent point, one which I had not thought of so far as teachers are concerned. Reducing the number of teachers in the educational enterprise would have the effect of reducing career opportunities for aides and assistants. Therefore, teachers should not view such personnel as being in competition with them.”29 The key idea for Selden was that paraprofessionals could be understood as teachers in training. This framing simultaneously promised advancement to paraprofessionals and assuaged teachers’ anxieties by defining paraprofessionals as apprentices. As Albert Shanker explained to an interviewer in 1985, “The way to think about this [program] is, this is going to be a generation of Black teachers in the future.”30

Writing to Riessman in December 1969, Selden asserted that “the AFT will be able to do a great deal to help the new paraprofessionals,” but “there will be a certain amount of subversion of your original concept. Most teachers are not interested in revolutionizing the nature of this service [education].”31 Selden’s vision both opened the door for para-to-teacher pipelines and asserted a hierarchical relationship between teachers and paraprofessionals.

Nonetheless, Selden was clear that AFT locals seeking to unionize paraprofessionals should commit to supporting career ladders. In the summer of 1970, as UFT paraprofessionals bargained their first contract, the AFT’s executive committee resolved that “all locals ask their school boards for paraprofessional programs” built on five principles: no educational restrictions for entry, pay increases based on education and experience, release time to pursue college coursework, college unit equivalencies for on-the-job training, and encouragement for “persons who are successful in such a program … to work toward the goal of entering the teaching profession.”32 In New York City, UFT paraprofessionals put all of this into their landmark first contract.

Free Training and Stipends for All

Velma Murphy Hill, who chaired the UFT’s paraprofessional bargaining committee, recalled that the New York City Board of Education’s representatives were incredulous of para-to-teacher pathways, telling her, “You know, they don’t want to go to school. These are women with families.”33 The board also feared the cost of developing a training program at such a scale, which had never been done before. Nonetheless, the UFT insisted, and the final contract promised that the Paraprofessional-Teacher Education Program (PTEP) at the City University of New York (CUNY) would expand dramatically to offer a place to every paraprofessional who sought one in the spring of 1971.34 Paraprofessionals would receive not only free education at the point of service—CUNY, at this time, was both free and open-admission—but also stipends and time off to support their education.

Hill still gets overwhelmed when she remembers the way New York City paraprofessionals responded. Early in 1971, thousands of paraprofessionals packed UFT offices in all five boroughs, jammed phone lines, and lined up around the block to sign up on the very first day they could. Hill spent the day driving across New York City to help overworked union staffers with tears in her eyes.35 “It was so beautiful to see them, you know, registering for school,” she recalled in 2011.36

By 1974, over 3,500 paraprofessionals—approximately one-fourth of the paraprofessionals employed in New York City—were taking classes at CUNY.37 In addition, approximately 400 paraprofessionals were earning high school diplomas each summer, over 3,000 had earned some form of postsecondary degree, and 400 were working as teachers in New York City.38 By 1978, over 1,500 paraprofessionals had become teachers, and one had become a New York State Assembly member.39 By 1984, the UFT reported that over 5,000 paraprofessionals had earned their bachelor’s degrees and 2,000 had become certified teachers through PTEP.40

Shelvy Young-Abrams, who started as a paraprofessional in 1968 and today is the chair of the UFT Paraprofessional Chapter and an AFT vice president, noted in 2015, “One of the things that struck everybody was the fact that we were given the opportunity to go to school. We were given an opportunity to make our life better.… You’d be surprised how many of us became teachers.”41 Beyond any single data point, the fact that all paraprofessionals had access to PTEP demonstrated that the UFT and city considered paraprofessionals to be capable educators and invested significant funds and energy in the possibility of their advancement.

As Velma Murphy Hill wrote in 1971, more than any other part of the UFT’s contract, PTEP defined paraprofessional work as “a profession with promise.” The contract was “more than a story of growth or of some improvement in New York City’s public schools. It’s also a story of economic justice.”42 Joseph Monserrat, a longtime Puerto Rican community organizer who chaired the New York City Board of Education in these years, agreed. At the creation of PTEP in 1971, Monserrat told his fellow board members, “Never has this need [to promote teachers from Black and Hispanic communities] been greater than it is now. Never have the stakes been as high: the continued existence of public education.”43 Monserrat’s urgent statement echoed Hill’s assertion in the same year: para-to-teacher pipelines were not simply a new form of teacher training and recruitment. They were a program of racial and economic justice to sustain public education in cities facing grave challenges in these years.

Para-to-Teacher Pathways Nationwide

New York City’s training program benefited from both the size of the UFT and the existence of CUNY, a massive free and open system of urban higher education. However, as paraprofessional educators joined AFT locals across the country in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the union wrote career ladders for paraprofessionals into contracts nationwide. The AFT also partnered with Frank Riessman and his team of “New Careerists,” who had become influential in the US Office of Education and particularly in its new Bureau of Education Professions Development (BEPD). Legislation drafted by one of Riessman’s collaborators, Alan Gartner, had established this bureau in 1968, and in 1970 the BEPD launched the Career Opportunities Program, or COP, to fund programs of paraprofessional hiring and para-to-teacher pathways.44

The COP directly funded the employment of nearly 15,000 paraprofessional educators in its seven years, serving hundreds of thousands of students in 132 districts across the nation.45 COP officials explained that the program’s goal was to generate a “precedent-setting arrangement” that would “spillover” into everyday operations at schools and universities.46 AFT locals proved instrumental in effecting this spillover, as they bargained the continuation of pilot pipeline programs. Hill became the chair of the AFT’s National Paraprofessional Steering Committee, traveling the country to support this work.

Implementing new training programs required site-by-site coordination and planning, and each city was different. In the most successful sites, such as Minneapolis, the COP worked with city, university, and union leaders and activists to build networks of opportunity. Minneapolis paraprofessionals took classes at several local community and technical colleges and could ultimately matriculate to the flagship campus of the University of Minnesota.47 The COP’s national publications regularly celebrated success in Minneapolis. Not only did many paraprofessionals become teachers, but by the late 1970s, unionized paraprofessionals earned the inflation-adjusted wage of about $35,000, the equivalent of what the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers and Educational Support Professionals struck for, and won, in March 2022.48

Not all cities had a flagship state university willing to host para-to-teacher training programs, but COP funds could still transform institutions of higher education, making them more welcoming to new kinds of students and programs. COP researchers reported that Shepherd College, a public institution in Shepherdstown, WV, moved from initial skepticism of the COP’s model to incorporating aide-type work into much of its elementary teacher training.49 In Pikeville, KY, Pikeville College—a “quiet, 71-year-old, church-affiliated college”—likewise developed a “heavy commitment to new clients, new forms, and, without compromising its academic reputation, new educational values.”50 This was the transformation advocates of career ladders hoped to effect: new models for teacher training, beyond any one program.

Across the country, AFT locals and the COP worked effectively together. The Baltimore Teachers Union negotiated career training for paraprofessionals in their first contract in 1970, much of which took place through the COP’s Baltimore program, COPE (Career Opportunities Program in Education).51 By September 1975, 93 percent of COPE graduates held teaching positions in the Baltimore City Public Schools.52 Kansas City Federation of Teachers & School-Related Personnel (KCFT) President Truman Holman partnered with the COP after paraprofessionals joined the KCFT in 1971. Detailing the union’s rationale for “a program of teacher development that elevates paraprofessionals,” Holman wrote in 1973, “these newly certified teachers are well trained, already possess several years of classroom and teaching-related work experience and are knowledgeable of [school district] procedures.”53 Every member of the first COP graduating class in Kansas City was hired by the school system.54 In Chicago, 118 of 142 degree-earning paraprofessionals became Chicago Public Schools teachers and CTU members, all placed in district-designated “target area” schools serving predominantly Black and Hispanic students. Finally, in 1975, the Oakland Federation of Teachers joined the COP in pushing for the expansion of the COP’s existing career ladder program. The union’s intervention won training opportunities for all of Oakland’s paraprofessionals.55

In firsthand accounts and formal studies, paraprofessional educators who became teachers earned high marks. “There is wide acclaim for the teaching ability of Follow Through paraprofessionals who have graduated and become certified,” declared the Bank Street College of Education’s Garda Bowman in 1977.56 In July 1974, the New Careers Training Laboratory at Queens College, CUNY (run by Frank Riessman, who had moved to CUNY in 1971), launched an evaluation of new COP graduates teaching within their local school districts. Its findings, reported in 1976, revealed “whatever the method of assessment … or the location of the survey, the outcome has been consistent: the COP-trained teacher is performing at least as well as [or] … better than her (or his) non-COP peers.”57

Reclaiming a Lost Legacy

Despite their success, both the Paraprofessional-Teacher Education Program at CUNY and the Career Opportunities Program fell victim to budget cuts and shifting political winds. After New York City’s brush with bankruptcy in 1975, CUNY began charging tuition and the Board of Education stopped paying for PTEP’s stipends for paraprofessionals. The UFT sued, but to no avail. UFT paraprofessionals continued to enjoy contractual access to career advancement—and do so to this day—but the walls around public higher education have risen precipitously. To exercise these contract rights, paraprofessionals must now navigate the labyrinth of application and university fees, financial aid, and regulations governing both the number of courses taken and course completion to guarantee reimbursement. These challenges are neither specific to the UFT contract nor the union’s fault; rather, they result from the transformation of public higher education over the last four decades from a system that was inexpensive and easily accessible to one that requires much more intensive individual commitment. Paraprofessionals in PTEP were part of the opening of the public university in the early 1970s; today, they contend with its limits in the age of austerity.58

The Career Opportunities Program, for all its success, was barely known in Washington, DC.59 As an increasingly conservative Congress rolled back antipoverty commitments, the COP was shuttered by the federal government in 1977. The final report of the program explained that “Teacher unions were involved in urban COP matters, to the considerable satisfaction of the participants, who felt themselves protected in the bureaucratic jungle and found union backing of career lattice arrangements to be a powerful weapon in their arsenal.”60 Para-to-teacher provisions persisted in the contracts of many AFT locals around the country, but without federal funding, programs proved harder to maintain.

The twilight of these early programs in the waning years of the 1970s highlighted the internal contradictions and challenges they faced. Even in New York, climbing the career ladder took a long time; the path for those who started without high school diplomas took six or more years, which led one paraprofessional to worry aloud that she didn’t “want to go to my teaching assignment in a wheelchair.”61 A study of PTEP published in 1977 noted, “Considering the obstacles, the motivation of most paraprofessionals must be great and be based on more than tangible monetary rewards.… Seven to ten years is a long time to hold three jobs (home, school, and college), jobs that do not end on the hour.”62

New York City’s numbers present something of a paradox: the 1,500 paraprofessionals placed in teaching positions in less than a decade represented the largest single influx of Black and Latinx teachers to New York City public schools up to that point in history. Civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, Velma Murphy Hill, and the AFT rightly lauded PTEP as a program of what Hill called “affirmative action without quotas.”63 At the same time, these numbers represented less than 3 percent of the teaching corps of 50,000 (in 1978) and only 10 percent of New York City’s paraprofessional educators. Most paraprofessionals did not succeed in becoming teachers—or they chose not to do so. The long-running teacher shortages precipitated by the baby boom faded in the 1970s, which, combined with budget cuts, further limited the possibility of paraprofessionals finding teaching jobs.64

Some scholars have argued that these low numbers contradicted the union’s assertion that para-to-teacher pathways would benefit most paraprofessionals or desegregate the teaching corps, which is 75,000 strong in New York City today.65 However, focusing only on paraprofessionals who became teachers understates the impact of pipeline programs. Thousands of paraprofessionals earned degrees in the 1970s, which not only meant better wages in their jobs as paraprofessionals but also gave them valuable credentials to carry into many types of future employment.66 And in a 1985 survey, just over half of UFT paraprofessionals reported that they wanted to become teachers (the same proportion as teacher aides reported in 1955), which suggests that para-to-teacher pipelines still mattered deeply to UFT paraprofessionals, even though far fewer than half would become teachers.67

At the same time, this steep climb, and the limited numbers of those who made it, proved problematic when training programs came to stand in for real contract gains for paraprofessionals in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Clarence Taylor, today a renowned historian of education, started his career as a special education paraprofessional in 1975 in New York City, the same year PTEP stopped being free and easy to access. In his recollection, “many of the paraprofessionals, in reality, didn’t take those classes,” and while the program was valuable, it also contributed to a larger “system of exploitation.”68 Pressed to improve working conditions for paraprofessionals, he recalls union leaders telling him that the best way to secure better wages was to become a teacher—a response that both ignored the real challenges of that process and devalued paraprofessionals’ existing educational labor. Herein lay the problem lurking in the vision David Selden articulated years earlier: considering paraprofessionals as apprentices in a hierarchical system, rather than partners in a robust vision for public education, meant holding up exceptional individuals as examples rather than supporting the entire workforce.

For decades after this first generation of para-to-teacher programs faded away, national policy discussions focused on the need to recruit ever-more-elite individuals to the teaching profession. From A Nation at Risk to Teach for America, arguments abounded that what the profession needed was more graduates of highly selective colleges. Unsurprisingly, paraprofessionals were absent from these discussions despite continuing to provide essential educational services in US schools.

Today, however, unionized educators are reasserting bold visions for the future of public education that are grounded in organizing with the diverse communities they serve. Pathways for paraprofessional educators to become teachers can and should be part of these efforts. However, programs for advancement should not be dangled as distant carrots in front of today’s hardworking paraprofessionals. Rather, as COP staff argued, they should serve as opportunities to empower paraprofessionals in schools and unions by highlighting all the essential ways that paraprofessionals contribute to public schooling right now in their current roles. As AFT Secretary-Treasurer Emerita and longtime paraprofessional Lorretta Johnson wrote in American Educator in 2016, “not all paraprofessionals want to become teachers, and that’s OK.”69

Paraprofessionals are not apprentices. They are educators of one kind, who, if they so choose, will excel in other educational roles. Para-to-teacher pipelines are not just about individual advancement. They are programs of racial and economic justice that can transform relationships between schools, communities, universities, and our unions as we bargain for the common good to reinvigorate public education.

Nick Juravich is an assistant professor of history and labor studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston and the associate director of the university’s Labor Resource Center. His research focuses on the history of public education, social movements, and public sector unions. His first book, forthcoming with the University of Illinois Press, is a study of paraprofessional educators titled, The Work of Education: Community-Based Educators in Schools, Freedom Struggles, and the Labor Movement.

Endnotes

1. Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, “Paraprofessional Career Development Program: Updates.”

2. L. Cabral et al., The Need for More Teachers of Color (Philadelphia: Research for Action, April 23, 2022).

3. B. Bond et al., The State of Teacher Diversity in Education (Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute, September 2015).

4. See, for example, Journey into Education & Teaching; TeachBoston, “Accelerated Community to Teacher (ACTT) Program,” Boston Public Schools, Office of Recruitment, Cultivation & Diversity Programs; TeachChicago, “Your Bridge to Teaching,” Chicago Public Schools; Los Angeles Unified School District, “Los Angeles Unified: Human Resources: STEP UP and Teach: Supporting Teacher Education Preparation and Undergraduate Program”; and Pittsburgh Public Schools, “District Announces Partnership with Two Local Universities to Launch Para2Teacher Program,” February 4, 2020, press release.

5. C. Park, “The Bay City Experiment ... as Seen by the Director,” Journal of Teacher Education 7, no. 2 (June 1, 1956).

6. F. Hechinger, “Teachers for Tomorrow: New Answers to an Old Question,” New York Herald Tribune, November 13, 1955.

7. L. Carroll, “The Bay City Experiment ... as Seen by a Classroom Teacher,” Journal of Teacher Education 7, no. 2 (June 1, 1956): 146.

8. On the Guild, see C. Cogen, “Letter to William B. Nichols,” December 7, 1955, United Federation of Teachers Records, Box 7, Folder 38, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University. On the NEA’s support, see Carroll, “The Bay City Experiment”: 142–47. On Chicago, see E. Todd-Breland, A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago Since the 1960s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

9. As a result of Black and Puerto Rican migration to the city and white suburbanization after World War II, New York’s public school system served a majority of Black and Latinx students by 1965. The Board of Education zoned these students into segregated schools, staffed by a teaching corps over 90 percent white. On school segregation in New York City, see, among others, A. Back, “Exposing the ‘Whole Segregation Myth’: The Harlem Nine and New York City’s School Desegregation Battles” in Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles Outside the South, 1940-1980, ed. J. Theoharis and K. Woodard (New York: Palgrave, 2002); C. Bonastia, The Battle Nearer to Home: The Persistence of School Segregation in New York City (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2022); A. Erickson and E. Morell, eds., Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019); and C. Taylor, ed., Civil Rights in New York City: From World War II to the Giuliani Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011). On the racial composition of the teacher corps, see C. Collins, “Ethnically Qualified”: Race, Merit, and the Selection of Urban Teachers, 1920–1980 (New York: Teachers College Press, 2011).

10. “Negro Teachers Form a New Assn. to Aid Harlem Kids,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, November 13, 1963; and Richard Parrish Papers, Reel 1, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. On HARYOU, see N. Cazenave, Impossible Democracy: The Unlikely Success of the War on Poverty Community Action Programs (Albany: SUNY Press, 2008); and A. Erickson, “HARYOU: An Apprenticeship for Young Leaders,” in Erickson and Morrell, Educating Harlem.

11. “A Proposal to Establish After School Study Centers in the Central Harlem Area and to Develop New Approaches in the Area of Remediation, Academic Instruction, Guidance, and the Training of Teachers,” Community Teachers Association, Richard Parrish Papers, Microfilm, Reel 3, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library; and L. Pires-Hester, interview by N. Juravich, March 9, 2015.

12. Youth in the Ghetto: A Study of the Consequences of Powerlessness and a Blueprint for Change (New York: Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited, 1964).

13. “Youth in the Ghetto,” quoted in A. Pearl and F. Riessman, New Careers for the Poor: The Nonprofessional in Human Service (New York: Free Press, 1965), vii.

14. A. Pearl and F. Riessman, New Careers for the Poor: The Nonprofessional in Human Service (New York: Free Press, 1965).

15. Clipping, New York Herald-Tribune, January 23, 1966, in the James H. Scheuer Papers, Box 6, Folder 3, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, PA. Congressman Scheuer used Riessman and Pearl’s rubric to draft the “Subprofessional Careers Act” in 1966 as an amendment to the Economic Opportunity Act, providing funds expressly for the hiring of paraprofessionals. In the same year, Commissioner of Education Harold Howe II singled out community-based hiring, urging school districts to use of federal monies to “tap every possible source of helpers in their own communities” in a June speech on the purpose of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, press release, June 30, 1966; and American Federation of Teachers Inventory, Part I, Box 30, Folder “School Aides,” Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit.

16. Letter from School Aides of Bronx Science to A. Shanker, March 26, 1964, Box 93, Folder 5, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University. New York’s school aides joined AFSCME DC 37 in 1966.

17. Women’s Talent Corps Progress Report (No. 2) (New York: United Federation of Teachers, October 1966), Box 108, Folder 5, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

18. Board of Education Special Circular No. 30, “Creating Paraprofessional Positions,” October 30, 1967, United Federation of Teachers Records, Box 155, Folder 1, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

19. G. Roth, Auxiliary Educational Assistants in New York City Schools, internal report (New York: United Federation of Teachers, May 20, 1968), 6, Box 80, Folder 11, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

20. Roth, Auxiliary Educational Assistants, 1.

21. Roth, Auxiliary Educational Assistants, 8.

22. On the 1968 teacher strikes, see, among others, R. Kahlenberg, Tough Liberal: Albert Shanker and the Battles Over Schools, Unions, Race, and Democracy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007); D. Perlstein, Justice, Justice: School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004); J. Perrillo, Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012; and J. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002).

23. For paraprofessionals’ early experiences in the classroom, see United Federation of Teachers, “Paraprofessionals Chapter 50th Anniversary,” June 21, 2019.

24. Letter from N. Garcia to A. Shanker, October 23, 1967, Box 93, Folder 5, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

25. UFT Paraprofessional Campaign Flyers, Box 155, Folders 2–4, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

26. Internal Report (New York: United Federation of Teachers, 1974), Box 80 Folder 13, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

27. Kahlenberg, Tough Liberal, 2–3.

28. Letter from D. Selden to F. Riessman, June 3, 1968, Box 155, Folder 2, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

29. Letter from D. Selden to F. Riessman, February 24, 1969, American Federation of Teachers Records, Office of the President Collection; and David Selden Papers, Part II, Box 5, Folder 1: New Careers, Paraprofessionals 1967–1971, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit.

30. Quoted in Kahlenberg, Tough Liberal, 128.

31. Letter from D. Selden to F. Riessman, December 12, 1969, American Federation of Teachers Records, Office of the President Collection; and David Selden Papers, Part II, Box 5, Folder 1: New Careers, Paraprofessionals 1967–1971, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit.

32. “Paraprofessionals,” 1970: American Federation of Teachers Records, Office of the President Collection; David Selden Papers, Part I, Box 10, Folder 41: New Careers, Paraprofessionals 1967–1971, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit.

33. V. Hill, interview by N. Juravich, November 7, 2011.

34. PTEP had been created in 1968, but it served fewer than 1,000 students until training opportunities were written into the UFT’s contract. R. Murphy, “The New Students at the City University of New York: How Are They Faring?,” in Paraprofessionals Today: Volume I: Education, ed. A. Gartner, F. Riessman, and V. Jackson (New York: Human Sciences Press, 1977).

35. V. Hill, “Address to Second Annual Paraprofessional Conference,” SUNY-ESC Harry Van Arsdale Center, Saratoga Springs, NY, April 2014.

36. V. Hill, interview by N. Juravich, November 7, 2011.

37. Murphy, “The New Students.”

38. Draft of full-page advertisement for New York Times, March 1974, Box 149, Folder 30, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

39. “Career Ladder Demonstrates Mobility: Union Moving for EFCB Approval of Para Contract,” United Teacher, Box 159, Folder 31, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

40. G. Goldenback, “Career Aspirations of Monolingual and Bilingual Paraprofessionals in New York City Schools,” dissertation, Hofstra University, 1985, 26–27 (data cited from correspondence with Maria Portalatin, chair of the UFT’s Paraprofessional Chapter at the time).

41. S. Young-Abrams, interview with N. Juravich, September 5, 2014.

42. V. Hill, “A Profession with Promise,” American Teacher, October 1971, Box 255, Folder 2, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

43. J. Monserrat, memo to Board of Education re: Education Program for Paras (Lachman Memo), December 16, 1970, Isaiah Robinson Papers, Series 378, Box 18, Folder 38, Board of Education Records, Municipal Archives, New York.

44. G. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher: The Story of the Career Opportunities Program (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1977).

45. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher, 43.

46. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher, 69.

47. A. Sweet, “A Decade of Paraprofessional Programs in Minneapolis Public Schools,” Career Opportunities Bulletin, 1975.

48. E. Shockman and A. Krueger, “Deal Reached to End Minneapolis Teachers Strike; Classes Expected to Restart Tuesday,” MPR News, March 25, 2022.

49. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher, 105.

50. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher, 110–11.

51. COPE Pamphlet, Board of Education Records, Chancellor Harvey Scribner Papers, Series 1101, Box 13, Folder 4, Career Opportunities Program.

52. W. Carter, “The Career Opportunities Program: A Summing Up,” in Gartner, Riessman, and Jackson, Paraprofessionals Today, 193.

53. Holman to Miriam Simon, Specialist III, EPDA Project KCSD, November 11, 1971, Kansas City Federation of Teachers Records, Box 10, Folder 21.

54. Carter, “The Career Opportunities Program: A Summing Up,” 205.

55. G. Kaplan, “The City as COP Turf,” Career Opportunities Program Bulletin, 1975.

56. G. Bowman, “Paraprofessionals in Follow Through,” in Paraprofessionals Today.

57. Carter, “The Career Opportunities Program: A Summing Up,” 212.

58. M. Fabricant and S. Brier, Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

59. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher, 43.

60. Kaplan, From Aide to Teacher. 69.

61. Collins, Ethnically Qualified, 64.

62. Murphy, “The New Students,” 168.

63. V. Hill, interview by N. Juravich, November 7, 2011.

64. Of 300 paraprofessionals who earned teaching degrees in New York City by 1974, the UFT was only able to place 100 that year. Murphy, “The New Students,” 179.

65. Collins, Ethnically Qualified. See also S. S.-H. Lee, Building a Latino Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

66. J. Mark, Paraprofessionals in Education: A Study of the Training and Utilization of Paraprofessionals in U.S. Public School Systems Enrolling 5,000 or More Pupils (New York: Bank Street College of Education, 1976), 40.

67. Goldenback, “Career Aspirations,” 120.

68. C. Taylor, interview with N. Juravich, February 11, 2015.

69. L. Johnson, “Looking Back, Looking Ahead: A Reflection on Paraprofessionals and the AFT,” American Educator 40, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 25.

[Photos courtesy of the United Federation of Teachers Photos Collection & Hans Weissenstein Negatives, Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.]