Our country is facing unprecedented challenges as we enter another election season: an ongoing pandemic that has sent mental health needs skyrocketing, conflict abroad and corporate greed that have led to painful inflation, trauma at home as gun violence claims more innocent lives, and increased efforts to bring culture wars into the classroom and strip public schools of needed resources.

In this conversation between four experienced educators and union leaders, we learn how elections impact all who work in public education and what issues are personally motivating them to head to the ballot box.

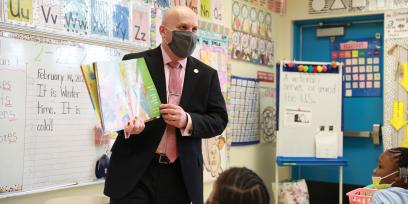

Nicole Capsello is a special education teacher, president of the Syracuse Teachers Association (NY), and at large director of the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT) Election Districts 7 & 8. Rebecca Kolins Givan is an associate professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and president of the Rutgers AAUP-AFT. Terrence Martin Sr., a former second grade teacher, is a vice president of the American Federation of Teachers and president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers. Andrew Spar, a former music teacher, is a vice president of the American Federation of Teachers and president of the Florida Education Association, the state’s largest association of professional employees.

–EDITORS

EDITORS: Tell us about your membership and the challenges they’re facing.

REBECCA: Our chapter of Rutgers AAUP-AFT represents full-time faculty, graduate workers, and counselors. We work closely with our sibling chapter that represents adjunct faculty and in coalition with unions across the university that represent all kinds of other higher education workers. Together we fight for a more equitable, sustainable, and accessible Rutgers—one that is a better place to study and work and that truly serves the higher education needs of New Jersey.

Like many others in higher education, we continue to face austerity budgets that are a result of the long-term trend of disinvestment in public education. In the name of austerity, our administrators have made strategic choices that don’t necessarily serve the university mission, such as threatening layoffs—especially of adjunct faculty—while spending millions on athletic priorities or administrative hiring at the highest levels. Meanwhile, tuition has gone up, which means student debt burdens have gone up significantly, and our students are increasingly worried about economic security. All of this is concerning to our members.

ANDREW: Here in the great state of Florida, the Florida Education Association represents nearly 150,000 teachers and school support staff, as well as higher education, student, and retired members, from Key West to Pensacola and everywhere in between. One of our top challenges is also state disinvestment in public education—in particular, our experienced educators. Florida ranks 48th in the nation in average teacher salary and 45th in funding for public K–12 schools. Our governor, Ron DeSantis, has invested in salaries for beginning teachers, but he did this by taking resources from experienced teachers. Today, experienced teachers are making less in real dollars than their counterparts did 10 or 15 years ago. So in addition to low pay, our members are facing lack of morale, steep increases in the cost of living, and a massive teacher and staff shortage—not to mention a catastrophic lack of unemployment insurance because state systems couldn’t support unemployed workers during the pandemic.

Instead of supporting our teachers, the governor has worked to pit them against each other. And rather than making long-term investments in public education, he has continued draining and underfunding our public schools, shortchanging our students, and showing a lack of regard for those who work in our schools every day to ensure that students get what they deserve and need.

TERRENCE: Our members are also feeling the results of years of austerity and disinvestment in public education by our elected officials. I represent the 4,500 educators who belong to the Detroit Federation of Teachers in Michigan’s largest school district—including academic interventionists, attendance agents, and long-term substitute teachers—and who are all committed to providing Detroit’s students and their families with safe, thriving, and welcoming public schools.

But nearly a decade after Detroit declared bankruptcy, our schools are still seeing the impacts of the drastic cuts to public education during that time—pay freezes, layoffs, and school closures—that devastated our communities. The damage was compounded by the years that the state had already been draining public school resources in the push to expand charter schools, particularly in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, causing severe problems for our district. Over the years, we’ve been in a multitude of fights about the ways these schools have been allowed to proliferate in our neighborhoods with few of the accountability measures required of traditional public schools, costing our students their schools and our educators their livelihoods. This has all been at the hands of legislators who know nothing about education and enact charter laws to compete rather than collaborate with existing public schools.

NICOLE: The Syracuse Teachers Association represents a broad array of educators and school-related professionals: food service workers, teaching assistants, school nurses, teachers, and more. We are among the 1,200 locals—with 600,000 total members—that are part of the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT). My local is an umbrella organization with four units, so I represent members on all income levels. A huge issue they have in common is the cost and availability of healthcare. We have a decent insurance plan in Syracuse because of our last contract, but the cost is still a concern. One insurance option has a deductible so high that we don’t offer it to our food service workers—it could never be cost effective for them. This problem extends beyond Syracuse; across the state, districts are passing more healthcare costs onto educators and school staff.

And although there’s a mental health epidemic in this country, mental health treatment is considered an out-of-pocket or out-of-network cost rather than a key part of our healthcare options. Our students also desperately need access to mental health programs—many local treatment clinics and programs have been shuttered for years and have yet to be restored. We need to fight for well-staffed and well-resourced mental health programs so we can better care for our students and members. And we need legislation at the federal level to ensure that comprehensive healthcare is affordable and accessible for everyone.

EDITORS: Why are elections so important, both generally and for public education?

TERRENCE: Many educators don’t fully realize how much elections can impact our ability to meet our students’ needs. I had no idea when I first started teaching that what happens in our classrooms is connected to what happens in the state capital. But it’s not a coincidence that for most of my teaching career, Michigan’s House, Senate, and governor’s offices were occupied by conservative leaders who did not value public education, and for most of my career, there’s been a struggle to get the funding and resources our schools need.

I’ve always believed that everyone deserves access to a union and to fairness and equity in their work. In Detroit, we have organized a couple of charter schools, and many of our charter school members are running into the same funding issues because our elected officials talk a good game, but by their actions they don’t value charter schools any more than neighborhood public schools. Our charter siblings work a longer school day and longer school year, and very few of them have contact with their school board members, who in some instances don’t live in Michigan and don’t know the needs of the community, the students, or educators. We need to change this. It’s not acceptable when educators, the experts in this profession and those who understand our community best, have no say in what happens during the school day.

The good news for the Detroit Public Schools Community District is that we now have a school board that is elected, rather than appointed, so it is responsible to the community. We need to elect folks to the board—and to positions at higher state and federal levels—who understand and appreciate what we do every day in our classrooms and trust that we know the needs of the students we serve.

REBECCA: Elections are important because threats to our democracy are real. Threats to public education are real, and there’s a clear difference in how much is invested in public education depending on who’s in power. Participating in and defending our democracy is our only opportunity to fight for and win specific resources to meet the needs of our students and those who serve them.

We need to make education affordable and accessible. We need to fight for student debt cancellation and for free college—New Mexico has just led the way on this, and we hope New Jersey can follow. We need to put a stop to the exploitation of underpaid adjunct faculty and ensure adjuncts have full-time, tenure-eligible positions. We need to ensure that everyone working in higher education—from faculty and support staff to groundskeepers, service employees, and students on work-study—are all paid a living wage. We need all workers to have access to a union through which to rebuild a secure workforce in higher education. These are our priorities, and these changes won’t happen unless we prioritize elections.

ANDREW: As a union, we need to make sure we’re connecting what’s going on in our members’ lives to the decisions being driven by school boards, policymakers, and legislators. Too often, the reality is that these decisions are not addressing students’ or educators’ needs. Elections allow us to influence these decisions so that we don’t end up with policies that make it more difficult to do our jobs well.

I know some of our members would rather just focus on their students and not on what happens with our elections. But to effectively help our students, we need good policies—and to have good policies, we must elect people who understand our work and its importance.

Public education must be a nonpartisan issue. Regardless of political preference, our members and the families in our communities overwhelmingly believe we should invest more in strong public schools for every child. Our job is to ensure that our leaders will support public schools—including their students and their employees—and that doesn’t happen if we don’t get involved in our elections.

NICOLE: The stakes for our students and our profession are too high for us not to get involved. Now more than ever, children need safe and welcoming environments, access to affordable mental healthcare, and a solution for food insecurities. We’ve been fighting for increased funding statewide for community schools* so that we can meet those needs in a greater way, but this requires the support of local and state leaders who are friendly to public education.

Getting that support will not happen by accident. Fortunately, NYSUT’s member density allows us to use our resources to train people for local, state, and federal leadership. This training program essentially teaches Politics 101: how to run for office and what it’s like to be part of a political campaign.

Several of my members went through the program and now serve as school board members in their districts. Our district’s state senator, John Mannion, is a former educator who also went through the program and won his seat. Educators all over the state who share our priorities now hold office, shaping policy decisions and advocating for our students.

This year, we have a congressional seat opening that Democrats have not held in over 20 years. This is a huge opportunity to elect someone who is going to prioritize public education and human rights for all. State Senator Mannion is also up for reelection. He has been an incredible advocate for students with special needs—which is close to my heart because I’m a special education teacher by trade. We need to ensure he is reelected so he can continue his work on behalf of our students as chair of the Senate special needs committee.

EDITORS: What opportunities are created when we elect people who share our priorities?

ANDREW: If we had the right people in office locally, at the state level, and in the US Congress, we could make real headway on key education issues. We could improve on the promise of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and expand the vital services that students with special needs are currently not getting because of funding limitations. We could deal with the student debt that saddles so many of our members and open more pathways to teaching for our education support staff. And we could increase support for our teachers, reverse some of the overregulation of our schools, and make sure that public schools—where 90 percent of Florida’s students attend—have the funding and resources they need.

Florida’s public colleges and universities are heralded as some of the best in the nation, but we are close to the bottom in pay for K–12 teachers and support staff, and too many lawmakers are continually working to bring down our education systems instead of supporting us in the work that we do. Getting the right people in office would mean more investment in our schools, our students, and our future—which ultimately builds our economy and helps our communities thrive.

REBECCA: I agree. Electing people who share our priorities means we have greater opportunity to invest in public education and in our communities. We’ve seen this at the national level since 2021, with the passing of the American Rescue Plan and then the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. But state and local elected officials are overseeing the funds available through these laws, so we need to fight to make sure that the funding is used to benefit our students.

When people who don’t share our priorities have been in office, we have seen increased efforts by some governors and legislatures to strip resources from our students and sow division among educators, families, and communities. We have seen vicious attacks on education and threats to academic freedom on multiple fronts.

One of the more concerning threats for us in higher education is the increasing intervention in tenure decisions coming from elected leaders and boards that are appointed by politicians rather than elected by the people. Probably the highest profile case was the tenure denial of Nikole Hannah-Jones at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. But what we’re seeing is that these politicized boards—frequently comprising wealthy businesspeople and allies of governors with no education expertise—are overriding the well-developed and structured processes established to make decisions about university operations, govern faculty tenure and promotion, and determine what actually happens in the classroom. This interference is tremendously dangerous; it risks our ability to educate and to do research.

TERRENCE: We have similar threats to academic freedom at the K–12 level with increasing attempts to keep our students from being exposed to honest history. Just a few years ago, Michigan legislators tried to decimate our social studies curriculum by limiting references to the Ku Klux Klan and the NAACP, among other topics; more recently, they advanced bills to restrict how teachers talk about racism, gender, sexual orientation, and sexism in the classroom. But when we elect leaders dedicated to honest history and inclusiveness, we’re better able to fight off these threats and bring widespread improvements to public education in our country.

If we elected more leaders who shared our priorities, we could not only address our teacher shortage and inequitable school funding problems but also grow our unions as we demonstrate that we respect and value all those who work in education—from the employees who prepare food, clean buildings, and drive buses to those who work with students in the classroom.

Our governor, Gretchen Whitmer, gets that. As an advocate for public education, she has increased funding for our schools and vetoed bills that would have funneled public funds to private schools. She has been steadfast in her support of our students and educators despite fierce opposition—and even threats to her life. Just a year ago, there was a plot to kidnap her, which is a clear sign of the danger our democracy is in when under the wrong leadership at the highest levels.

Governor Whitmer has an ambitious plan for investing in public education and pandemic recovery for our students on a scale we haven’t seen in decades. It’s important for us to reelect her this year so that she can continue to push for the changes that we need in Michigan.

NICOLE: In New York, our challenge for the upcoming election is mainly keeping likeminded leaders in office so that the progress we’ve made doesn’t get overturned. Thanks to the leaders we elected, we haven’t struggled with book bans or attacks on academic freedom like other states have—but we can’t become complacent. The pendulum can swing suddenly, and we could easily end up with educational policies that hurt our students and our members.

That’s why NYSUT has built a strong, well-structured political arm to help us fight for the education our students deserve. Part of my work as a NYSUT at large director (which is a regional elected position) is ensuring that we support local political candidates, including school board candidates, who will advocate for public education. We also have regional political action coordinators who work with state and federal representatives on education legislation and a 100-member committee of local leaders that lobbies as one collective for the issues we care about.

We’ve won significant victories for our students and members. We passed reform in our retirement system so that workers serving our state have access to a fair pension. We won an overhaul of the time-consuming, expensive performance-based assessment required to become a certified teacher in New York state—which was exacerbating our already critical teacher shortage—and are replacing it with a more equitable process. And after a lawsuit against the state, we’ve finally been able to get much-needed funds released for our schools that the state has owed our districts for decades.

EDITORS: What, in your opinion, is the end goal of officials who do not want to invest in public education?

NICOLE: I think there’s an agenda to privatize our education system. In New York, the first step is to dramatically increase the number of charter schools. We see this in the receivership law that we’ve been fighting for years, which is just a convenient way for policymakers to turn our system over to charters. The law has destroyed so many schools in the name of “school improvement” by adding onerous and punitive regulations on top of the accountability measures schools must meet under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). When a school goes into a receivership designation, the testing and data reporting requirements to show the state that we’re doing what’s best to turn the school around are terrible for our students because they take too much time away from teaching and building relationships. Many teachers have reported spending about 40 percent of their instructional time on these requirements; they have also been given scripted curricula and pacing guides that are developmentally inappropriate for students.

Meanwhile, the charter schools that drain money from traditional public schools aren’t held to the same standards. NYSUT is fighting for federal legislation to ensure an equal level of accountability between traditional public schools and charter schools. It’s a huge undertaking, but we need to see change.

ANDREW: In Florida, there’s a clear agenda to eliminate public schools and create a universal voucher system. Some people refer to it as education savings accounts or scholarships, but the idea is the same: they want to wash their hands of the idea of public education for all. Texas Governor Greg Abbott essentially admitted this when he said he was considering a challenge to a longstanding Supreme Court ruling that access to public education is a constitutional requirement for all children in the United States, including undocumented children. This extremist idea that we don’t need to educate people has been seen elsewhere in the world, and we know it doesn’t work. Not only that—it’s anti-American. America was founded on the premise that we need an educated electorate. And if you consider our country’s history of voter suppression, it’s largely been based on trying to keep people from getting the education they need to participate in our democracy.

The privatization agenda is also clear in the coordinated attacks on our schools and teachers. Our country is experiencing the worst teacher shortage I’ve ever seen, but instead of crafting solutions to recruit more teachers and keep experienced teachers in the profession, those who are anti-public education are vilifying teachers and pushing the false narrative that our students are being taught to hate themselves—or to hate law enforcement, as our governor has claimed. It’s an attempt to turn families against teachers and cause families to doubt what they overwhelmingly believe: our teachers care about and want to do right by their students.

REBECCA: I absolutely think the long-term trajectory of disinvestment is about maintaining power and control by having a less well-educated population. Highly educated voters are a threat to some people, so higher education becomes a threat. There are also anti-tax warriors who don’t want to do anything that requires public money, even things like education that have a multiplier effect for society.

Education is a societal good; economists have repeatedly shown that an educated society can better innovate and compete in the global economy. That’s why we fund K–12 for all students, and it’s one of the reasons we need to invest more into higher education for all. But this objection to education is not just about the money; some anti-tax proponents have an ulterior motive to restrict who has access to education. This becomes clearer when you see that the political attacks on higher education—particularly claims that maintaining adequate funding for public colleges and universities was unaffordable—began after people of color started accessing higher education in greater numbers. It’s a form of gatekeeping (different from prior generations’ segregation) driven by a politics of grievance: “Why should we invest when those who look like us are not benefiting?” Now that the student body is more diverse, many elected officials see higher education as an individual good, not a societal good. The same thinking underlies rhetoric against student debt cancellation: “We didn’t make that choice; we shouldn’t be subsidizing it.” Encouraging people to think that their money should not be spent on anything that they don’t directly benefit from is a strategy to sow division, make higher education and all the doors it opens less accessible, and keep middle and working-class people from building solidarity.

TERRENCE: As Andrew said, many states are trying to get out of the business of educating the public, so yes, this is an attempt to dismantle public education. But I love that Rebecca brought up solidarity, because I also think the attacks on public education and attempts to divide the middle and working classes are deeply rooted in an effort to weaken unions. That’s why the attacks blaming teachers for the ills of public education are being used to eliminate tenure protections and strip our ability to collectively bargain teacher placement, observations, or discipline.

An electorate that has been weakened by the undermining of its unions is less likely to show up at the ballot box and fight back. We’ve seen that here in Detroit—a town that was once extremely union strong but has continued to lose at the ballot box for years. We’re just starting to reengage and gain back some power, and we have to use it to get folks to participate in elections and in our democracy. That’s the only way our city will see real change.

EDITORS: What are some of the issues driving you to vote?

NICOLE: When I go home and take my union hat off, I am a mom, a wife, a daughter, a sister, and a strong independent woman. What do I want from our elected officials? I want rights and protections for women and children that are at least equal to the rights and protections that guns have. I want to know that my daughters will not have to battle, like I have, to pull up a seat at any table they choose and have their voices heard without being immediately knocked down a notch for being women. I want us to elect people who want equality and human rights to be protected—and I want us to vote out those officials that don’t value all humans equally.

REBECCA: We are in a critical time right now because the priorities of many of our elected leaders show that they don’t value all humans equally. So many of the issues we’ve talked about here disproportionately affect people who are already marginalized: Black and brown communities, LGBTQIA+ individuals, and people who need access to and choices regarding reproductive healthcare. I think any hope of getting significant investments in public education and stronger protections for these communities (and all who work in education) depends on the outcome of our next election.

I’m also concerned with broader issues like mass incarceration and the legalization of cannabis that might not seem closely connected but are critical to educators if we’re serious about prioritizing equity and education. Mass incarceration is much more expensive than education, and it robs people, especially Black people and others of color, of opportunities to make a living, to support a family, and to survive, let alone thrive, in our society. And we can’t have a discussion about cannabis without acknowledging the racially discriminatory laws that harmed cannabis users and dealers of color far more than their white counterparts. White people have long used and sold cannabis at the same rates but have relatively rarely been ensnared in the criminal justice system. Legalizing cannabis not only potentially rights this injustice but also creates a massive taxable good that can be invested in our priorities—like education.

ANDREW: I’m concerned about mental health and the ways that the strain of the last two and a half years—and the dramatic decrease in our civility to each other in that time—are impacting our children. We’ve heard from a lot of our members that student discipline issues are at an all-time high, and a lot of that has to do with what students are seeing in society. Not only are they still experiencing the stress and anxiety of dealing with a pandemic, but they’re also witnessing the fallout from a very politically divided country: disagreements devolving into name calling and physical altercations, the storming of the capitol on January 6th, and generally reprehensible behavior unbecoming of adults and citizens of our country—some of whom are our students’ family members. This is all impacting their behavior, and it does not bode well for the mental health of our students or our members.

We need to be able to talk with each other without incivility and without overruling or shutting down anyone we disagree with. We need to be able to teach honest history—the good and the bad—without fear of being silenced or losing our jobs. This is how our students will learn how our democracy works. This is how we give them the education they deserve and need.

TERRENCE: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what our students deserve and need. Over the past two years I’ve had more conversations with my 15-year-old son about three things than any other topics: health, safety, and security. We talk about health because he and his classmates have been afraid for their physical health during this pandemic, and at the same time their mental health has suffered because of all they’ve seen and endured with the rising racism, police brutality, and attacks on Black, brown, and other marginalized people in this country. We talk about safety because my son doesn’t know if police are going to attack him when he walks to the store or if white supremacists are going to hurl racial epithets—or worse—at him as he’s representing his team at a basketball game or a track meet. We talk about security because our school buildings should be sanctuaries for students, but at any moment, someone who ought not have a gun can turn schools into places of chaos, death, and fear.

Our children are concerned about their health, safety, and security more than at any other time in our recent history. And we need people in office who are going to see them as human beings who deserve to be happy, healthy, and whole. I look at my son and at young people around the country who are standing up for these three issues, and I feel hopeful about the future because I know our children are concerned about the right things. What’s important to them—getting back to being decent to one another and caring for each other—is what should be important to us.

EDITORS: How can members get involved?

REBECCA: Vote. Even if no candidate or policy platform is perfectly aligned with your own goals, the outcome of our elections is so critical that we must participate. But voting is the minimum; for union members, it’s where our work should begin. There are so many opportunities to get involved leading up to an election: you can volunteer for text or phone banking to encourage others to vote. You can volunteer to go door to door in your own state or go to a swing state or swing district to help register voters—or just help get out the word about when and where people can vote.

After the election, we need to follow up with ongoing activism, working with the people we elected to have our priorities heard and acted on. We also must work in solidarity with our coworkers and communities to hold our candidates accountable and make sure they continue to be strong, effective advocates.

I think we’re in a moment now when people are excited about unions and the labor movement. There are some tremendously energizing organizing drives going on across the country, and it’s essential that we see ourselves as part of a broader movement to build a nation that is better and more just for all working people.

TERRENCE: Voting is the minimum that we can do, but we have to start there. People are questioning our democracy now more than ever, and false claims about “fake news” and the “Stop the Steal” lie have damaged people’s belief in government and in voting. But voting is an essential vehicle for change. If we’re going to restore the belief that government can work for the people, we have to prove we believe it ourselves and vote.

It may sound impossible because of the financial challenges we’ve discussed that are facing educators, but we also have to donate. It costs money to support candidates and causes we believe in, and we shouldn’t be afraid to give as much as we can to help amplify our messages and our priorities.

And we need to talk with each other—yes, about the challenges we face, but also about our hopes for the future. In a national conversation that is too often focused on blaming teachers for what’s wrong with public education, we should be lifting up our profession and proudly sharing our accomplishments and the ways that we show up, every day, for our students and communities.

ANDREW: Educators vote for the same reasons that we show up for our students every day: we are passionate about helping others and we care deeply about our students’ futures. But we could do a better job of bringing everyone we know with us to the polls and making sure they also vote to support our public schools. And we could do a better job of building relationships with our elected officials, whether we agree with them or not, and finding ways to get the resources our schools need and our students deserve.

We can also advocate for our profession in our communities. We need to talk about our challenges—that we struggle to put food on the table for our families and how we routinely put the needs of others’ children ahead of our own children. People know that teachers do amazing things, but they don’t really understand the sacrifices that we make. We do ourselves a disservice when we miss opportunities to amplify our message and help create change.

Avenues like the AFT Teacher Leader Program are another opportunity to elevate our profession and our priorities. We need to assert ourselves as the education leaders we are, instead of continuing to allow nonpractitioners to influence our curricula and shape our policies. We are the experts, and we need to reclaim our profession.

NICOLE: I couldn’t agree more. Educators know what our students need; that’s why NYSUT supports and trains past and present educators to run for school boards and other offices. Through our Member Organizing Institute held each summer, NYSUT also helps members elevate public education issues and priorities. And this year, we’re sending members into our communities to register people to vote and rally support for the candidates we’d like to see elected in November.

There’s much at stake in every election, but the upcoming elections are critical for all who care about public education in this country. That’s why we all need to vote, and beyond that, why we need to be active in the work of our union to effect change for our students, schools, and education professionals. Together, we can create a path to a better life and a better world for us all.

*To learn about community schools, see “Building Community with Community Schools” in the Summer 2021 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

[Photos: courtesy of Nicole Capsello; courtesy of Rebecca Kollins Givan; courtesy of AFT Michigan; courtesy of the Florida Education Association; Lori Higgins/Chalkbeat]