Hundreds of black educators inspired one another with pledges to excellence, and shared tools to help their students achieve it, at the National Alliance of Black School Educators annual conference Nov. 15-19, celebrating the core message of the gathering: Black educators are key to the success of new generations of students who need the experience, example and discipline they can offer. From confronting low expectations to valuing the strengths of every lived experience, examining bias and teaching cultural relevancy, the conference addressed the best ways to reach students of color and to grow the ranks of educators who look like them.

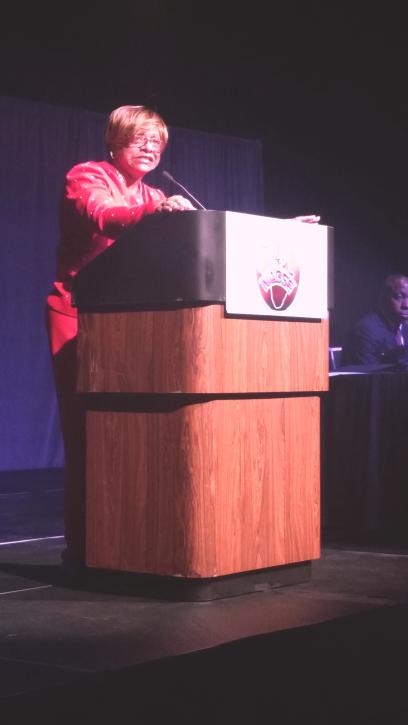

"We have to be the truth-tellers," said Marietta English (pictured below), president of NABSE, president of the Baltimore Teachers Union and an AFT vice president, who presided over the conference. "We have to talk about all that is right about black education."

Studies show that when students of color have teachers of color, they are more likely to succeed academically, less likely to be suspended and more likely to graduate. But 82 percent of the teachers in the United States are white, even though non-white students are projected to make up more than half the student body by 2024. Statistics are even starker in urban schools.

In addition, inequity persists. "I don't see an achievement gap, I see a bias gap," said keynote speaker Melissa Harris-Perry, the Maya Angelou Presidential Chair at Wake Forest University, noting "massive public disinvestment" that disproportionately affects low-income districts where many black students live. Segregated schools perpetuate inequity as well—including charter schools, which are not held accountable. Harris-Perry also slammed for-profit colleges for "eating our young people alive" with abysmal graduation rates and notoriously inferior education, and she decried the lack of attention given to the unfair treatment of black girls, who are suspended at a rate six times that of white girls. (Black boys are suspended at a rate three times that of white boys.)

Speakers like Calvin Mackie, founder of STEM NOLA, a program that enriches science, technology, engineering and mathematics training for underserved students, urged educators to "stand up and fight for our children, especially in a time like this when things are being dismantled," to be sure that they get the skills, resources and mindset they need to succeed, and that they understand their innate intellect and aren't distracted by expectations that they all become athletes and forget about books. "We've got to be training our kids from the neck up and not just the neck down," he said.

NASBE awarded scholarships to prove the point and celebrate academic achievement. (See photos below of recipents.)

Training teachers for tomorrow

The conference also focused on increasing the number of black educators, with a "Grow Your Own Teachers" leadership summit, developed last year and co-sponsored this year by the AFT. It covered culturally relevant pedagogy in schools of education, recognizing bias and the importance of valuing cultural conventions and experiences, including those from students whose families are not academically educated but may have a different kind of wisdom and strength. "If you don't consider ethnicity, you don't consider the whole child," said Wil Parker, an education professor at Bowie State University, who recommends putting education students into groups that are "uneasy and rare, to talk about racism and get real about bias."

That's especially important when a new teacher has no experience interacting with black people, beyond media coverage and sports, said Baruti Kafele, an education expert and urban public school educator. Educators must also consider trauma that urban children may have experienced, added William "Flip" Clay, a school counselor who described the "emotional psychological incarceration" many black boys experience when they are prevented from expressing emotion despite trauma.

At a workshop led by NYC Men Teach, an organization that recruits men to New York City public schools, leaders described successful ways to support African-American male education students with mentoring, professional development opportunities and tools like restorative practices. Keeping black males in the profession has a profound effect on black male students who, said Brandon Corley, a United Federation of Teachers member and NYC Men Teach program manager, immediately relate to them and are likely to listen and learn more quickly on that common ground.

"I only had one black male teacher despite being in a black school district," said Travis Rodgers, of Education Testing Services, at another workshop. "He set the standards for me, set higher expectations, set the idea of a kid from Baltimore going to a top-10 school. I went from being considered 'slow' to being considered talented and gifted in one year. My goal is for everyone to have that experience."

Educators did not turn away

John King, former secretary of education under President Obama and now CEO of Education Trust, described his own experience as an example of the need for strong teachers. His mother died when he was 8 years old, and his father, who had Alzheimer's disease, could not care for King. "School was the one place that was safe and supporting," he said. After his father died, he was kicked out of high school—but again, educators did not turn away. "That second chance is what propelled me to go on to college and be here today," he said.

King urged his audience to fight with him for high-quality preschool for all; well-resourced, well-rounded education for all; and safe and supportive schools for every student. Currently, student spending varies by as much as $15,000 per student from low-income and high-income districts, he said; AP classes are disproportionately unavailable to African-American students; and black students are too frequently suspended from school. To fix these issues, teachers must be culturally competent, and educators like one principal he met, who dismissed his school's low test scores because students lived in "the projects," must never give up on children but recognize their challenges and nurture their innate potential.

Recalling the anniversary of Ruby Bridges integrating her Louisiana elementary school, King said we do not have to wonder whether we would have been willing to risk our bodies the way she did, the way civil rights activists did. "We are there now," he said. "We have a responsibility as educators to stand up for social justice."

[Virginia Myers]