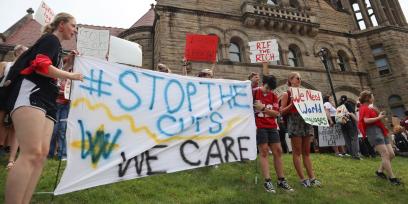

When West Virginia University announced deep cuts that would eliminate 28 majors and, over the course of 2023, lay off 281 faculty and other employees, the campus community was in an uproar. Demonstrations crowded the lawn outside the historic administration building, with students, faculty and staff protesting the elimination of world language, arts and education programs and more. But despite protests, the cuts are going through, and reverberations are being felt far beyond the WVU campus.

On Oct. 10, AFT and American Association of University Professors leaders came together for a panel to discuss what they flagged as a “downward spiral” in funding for higher education across the nation, exploring the details with WVU faculty and students, considering similar cuts at the University of Wisconsin, and thinking about the implications for colleges and universities everywhere.

“Austerity budgeting is starving higher education of the resources we need to fulfill the institutional missions and to serve our students, their families, the surrounding communities and the states,” said AAUP President Irene Mulvey, who is also an AFT vice president. Higher education is essential for a functioning democracy, she added, “a ladder into the middle class, an engine of social mobility and a community builder.

“Higher education at its best is an opener of minds, an opportunity for students to meet and learn from people from different backgrounds with different perspectives, an occasion to learn, to ask hard questions of oneself and others.” For those reasons, the attack on public education, both K-12 and higher education, is especially egregious.

West Virginia’s story

Jessie Wilkerson, a WVU history professor and a member of the West Virginia Campus Workers, described the WVU decline as having started a decade ago; higher education funding from the state has dropped 24 percent since then. “Like many places, we now rely on tuition revenue more heavily than we ever have,” she said. At the same time, enrollments have steadily decreased since 2014, so tuition dollars are diminished. Nevertheless, upper administration at the university went on a “spending spree” to update facilities and invest in real estate.

In March of this year, the administration announced a budget deficit, and faculty and staff learned there would likely be layoffs, even among tenure-track faculty. The first wave came in June, when 135 people lost their jobs, most of them staff. Then over the summer, 48 percent of WVU’s programs were required to complete self-studies as part of an academic portfolio review. Three days before classes started, the results of those reviews came in, and administrators announced 28 programs would be downsized or cut; 159 faculty were slated for layoffs.

Among the programs on the chopping block are world languages, soil sciences, education and public administration. “What unites them is that they serve the public,” said Wilkerson.

Workers and students led rallies and protests against the cuts. In September, faculty voted “no confidence” in University President Gordon Gee for mismanaging the school’s finances, and they demanded an immediate freeze on the euphemistically labeled “academic transformation” that has gutted programs and staffing.

“I‘ve been really inspired by the students and many of my colleagues who are framing the struggle as a fight for the people’s university,” said Wilkerson. “Some of my students talk about being third- and fourth-generation WVU students. This is their flagship university where they can study with reasonable tuition and have access to scholarships.” As programs disappear, opportunities disappear with them. “We are trying to reclaim that narrative of the public university, and we are fighting for that.”

Wisconsin’s historic and ongoing fight

Many people don’t realize that when the University of Wisconsin lost collective bargaining rights in 2011, that loss came with a “huge budget cut” of $250 million, said Jon Shelton, vice president of the AFT-Wisconsin Higher Education Council, professor of democracy and justice at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, and a member of the AFT Higher Education program and policy council. Then in 2016, then-Gov. Scott Walker took away tenure and shared governance—plus another $250 million. “We’ve had austerity imposed on us and tuition frozen for over a decade,” said Shelton.

Things have only gotten worse, with inflationary pressures coupled with a hostile state Legislature that leans heavily to the right. Inspired by national figures like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, the Wisconsin assembly leader has proposed a $32 million budget cut to higher education because, said Sheldon, “That’s the amount they think we spend on DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion programming].”

The University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh is expecting to lose 300 staff and faculty positions. At Shelton’s own campus, the theater department has been asked to come up with a plan to eliminate its own major.

“We’re in a position where Republicans in this state frankly don’t want us to exist, because they see what we do as being threatening, [trying to build] the kind of multiracial democracy that we deserve.”

“There’s no way we’re going to give up DEI,” said Shelton. “But we’re also not going to let them completely crush public education in this state.” Protesters from across the University of Wisconsin system have walked out, demonstrated for no cuts and fought against administrative bloat.

Mulvey rallied the group to keep fighting. “The faculty, who are the heart and soul of any university, must demand and fight for solutions that preserve and strengthen the core academic mission,” she said. The AAUP has policies and reports that support that mission, and members can access that knowledge and research to bolster the fight.

[Virginia Myers]