The concept of moral injury* in healthcare gained attention six years ago, with a viral article in STAT that has been downloaded 300,000 times and is still one of the publication’s most read articles ever.1 The coronavirus pandemic intensified interest in the concept, and some investigators began quantifying the experience,2 while others looked at potential sources and drivers of the distress.3 I am a psychiatrist who worked for the Department of Defense and as an executive for an international nonprofit before turning to address clinician distress full time. Along with Simon Talbot, an academic plastic surgeon with a subspecialty in hand surgery, I have been working for nearly a decade to address clinician distress. During that time, we have searched for an organization that minimizes the risk of moral injury to hold up as an example, to no avail.

We have followed up on every lead from either leadership or clinicians that promised a positive work environment. We have talked with facilities across the country, from small clinics to independent hospitals to large academic medical centers representing both for-profit and not-for-profit institutions. One organization we visited is representative of the pattern we repeatedly encountered: the health system draws people from 100 miles around with its great outcomes and happy patients, and we hoped to learn its secrets for maintaining excellence and, presumably, a healthy workforce. But we barely had time to introduce ourselves before the president slapped the conference table and said, “We’re so glad you’re here. We’re in big trouble.”

A few organizations manage well in isolated areas, or for short periods, but none have stood out as providing excellent patient care in a way that is sustainable for clinicians over several years. In virtually every case, as Dr. Danielle Ofri, an internal medicine physician at Bellevue Hospital in New York City and an expert on doctor-patient relationships, has written, under the strain of profit-driven corporate healthcare, adequate patient care has come to depend on the “one resource that seems endless—and free—... the professional ethic of medical staff members.”4 In too many places, clinicians are sacrificing their own well-being to uphold the oaths they made to patients.

Dr. Don Berwick, the founder of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and a career-long change agent in healthcare, wrote in June 2020, “When the fabric of communities upon which health depends is torn, then healers are called to mend it.”5 While the article was published shortly following the most intense period of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Berwick’s piece was not pandemic-centered. He spoke extensively about the sociopolitical environment in which communities exist and healthcare is delivered, arguing that health workers must insist, in whatever ways are available to them—voting, writing opinion pieces, working with community agencies, and others—on fundamental shifts in our collective commitment to moral change.

The foundation of professionalism in medicine, nursing, and other health professions is the covenant each individual makes with society to provide services that society is unable to provide for itself, in exchange for certain privileges: a comfortable living, respect, and the right to define and enforce appropriate practice. These privileges are rooted in the presumed integrity of the individuals entering the professions—in trust. Global risks to integrity, then, put professionals and their professions at risk. As such, it behooves individual clinicians to hold their organizations responsible for creating work environments in which their integrity is not threatened, either directly—by being asked to put the best interest of the organization ahead of the best interest of the patient, for example—or by association with an organization that does not uphold its own mission, vision, and values.

Patients present to health systems with a mental picture of what they imagine their care will be like based on the marketing materials they have seen, their interactions with medical staff, and perhaps the institution’s reputation among friends and family. Some of those expectations are conscious and reasonable; others are less so. When encounters fail to meet their expectations, patient responses may range from resignation to rage to abandonment of care, with potentially significant impacts on their health outcomes, well-being, and relationships with future health professionals.6

Clinicians, too, come to health systems with expectations for their experience of working for the organization. Those expectations come from mission, vision, and values statements and other public documents; job posting language; human resources interactions; and triangulating interviews and conversations with current and former staff. When a health employer’s culture fails to meet a clinician’s expectations for what their work will be like and the care they can provide, clinicians, like patients, have a range of responses. They may feel angry, ashamed, embarrassed, or even betrayed by the marketing slogans that some organizations admit are “puffery,” not meant to be truthful.7

Workers usually explore other employment options when they realize their situation is not as originally promised, but too many find their exit is blocked. Employment contracts with restrictive covenants, also known as noncompete clauses, bind nearly one in five workers in the United States and prevent employees from working for a competitor in the same market.8 An astounding 57 percent of healthcare employers use noncompete agreements.9 Many also use training repayment agreement provisions (TRAPs) to reimburse companies for training costs when an employee leaves soon after receiving said training.10 Nearly one-third of nurses are subject to TRAPs sometime during their careers.11 Yet others face sign-on bonus repayment for early termination of a contract. These contract mechanisms are meant to retain employees through contractual or financial leverage, rather than through enticements such as raising wages or improving working conditions.12 When such leverage compounds an employer’s failure to meet expectations, the risk of betrayal and consequent moral injury is high.

Recent surveys have highlighted increased levels of burnout between 2018 and 2022, which correlated with distrust in management, lack of supervisor help, not enough time to complete work, and a workplace that did not support productivity.13 There have been striking findings about moral injury, too. In 2020, 45 percent of workers responding to the Moral Injury Events Scale agreed with the statement “I feel betrayed by leaders who I once trusted,”14 and 41 percent of those responding to the Moral Injury Symptom Scale for Healthcare Professionals met criteria for moral injury.15 Despite increased attention to health workforce mental health and well-being during the pandemic, symptoms are not receding as intended. Moreover, since 2007, when the Cleveland Clinic first created a chief wellness officer position, dozens of large hospitals have followed suit, with the trend accelerating over the last five years. The American Medical Association even recommends creating the position as a first step in addressing staff distress. Unfortunately, none of these measures is having the hoped-for level of impact.

In the spring of 2023, with researchers in the United Kingdom, our organization, Moral Injury of Healthcare, set out to develop an international consensus among those who specialize in moral injury. We wanted to know what characteristics a non–morally injurious, or morally centered, organization would exhibit. We wanted to describe a North Star toward which leaders can navigate, and for which unions and frontline staff can advocate.

More than 50 individuals with suitable expertise in moral injury, from either an academic or a clinical perspective, were identified through professional networks, literature searches, and advertising on LinkedIn. Invitees came from around the world and from a cross-section of fields—healthcare, first responder communities (including law enforcement), and the military. Only a handful of invitees declined the invitation. Some participants had done research in moral injury for decades, and others had never done research but were part of wellness teams in hospitals or clinics. Over three months, we presented iterative questionnaires focusing on how to describe morally centered organizations, and then delineating the characteristics of such institutions. Some descriptions were based on organizations known to be performing well in some areas, and others were descriptions of envisioned ideals. There was strong consensus about the findings described below, despite participants representing diverse perspectives.16

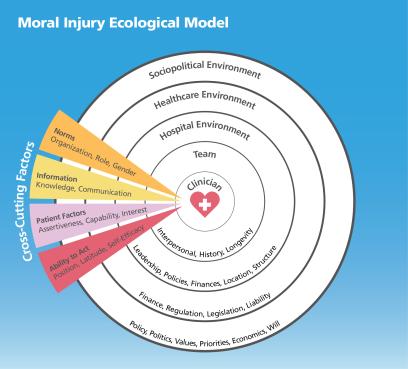

Ecological models are well known in health literature, representing the multiple levels of influence impinging on health behaviors and outcomes. Moral “health,” similarly, is influenced by factors at many levels (as shown in the figure below): an individual’s background and upbringing, interpersonal factors among team members, the hospital environment and leadership, the environment of healthcare writ large, and the general sociopolitical environment in which care is rendered. Viewing the findings through the lens of an ecological model, from sociopolitical to hospital environments, provides a logical progression, with one caveat: this is a discussion of the characteristics of a morally centered organization, and as such, it will not include characteristics of individual sufferers to be addressed, nor solutions focused on individuals.

A Moral Core

Mitigating moral injury begins by aligning outward representations of corporate culture with manifest corporate conduct. In other words, the words on the walls must match what happens in the halls. A culture predominated by a values-based framework, which balances compliance-centric rules with an internalized set of shared professional values, encourages intuitive decisions that are “right” for serving patients’ best interests. Organizations with cultures that inspire people to excel at patient care, and operational environments that facilitate their doing so, are places where clinicians thrive.

These organizations recognize practitioners as knowledge-worker professionals. Professionals, by definition, have a unique fund of knowledge, based upon which they provide services to society that society cannot provide for itself. These practitioner-professionals are trained to make complex judgments, with integrity, under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty. Their judgments then lead them to take highly skilled action. Nurses, physicians, and other health practitioners are hired specifically for their unique knowledge and skills (and those with such unique skill sets can be identified by the extensive credentialing process meant to prove their claims). Because no one else—other than a similarly or more highly trained professional—is qualified to intervene in their decisions, healthcare professionals must be free to act on their training and ethical principles, without confounding demands, such as admission quotas, documentation requirements, and length-of-stay constraints.17

In a healthy environment, professionals exercise their education and training as they deem appropriate and are responsible for decisions in their areas of expertise. Practitioners control a health system’s decisions that impact patient care and clinical workflow, for example. Administrators value clinical input and work to facilitate optimal care delivery that is sustainable for practitioners. This, of course, requires careful selection of clinical and nonclinical team members, for those who are mature, self-aware, and introspective; have values aligned with the organization; and demonstrate high integrity. The organization anticipates that the potential for moral challenges is ever-present in healthcare workplaces. However, while some moral challenges are unavoidable, as in critical or crisis care situations, avoidable moral challenges, like administrative encroachment on clinical decision-making, are minimized.

Facing the risks of moral injury and engaging in honest, courageous conversations about threats to our moral foundations requires leaders who are, first and foremost, trustworthy. They are sufficiently skilled for their roles, exhibit high integrity, and deliver on promises. They are humble, vulnerable, authentic, and engaged, and they select other team members, clinical and nonclinical, who are the same, while reinforcing these characteristics. Such leaders model morally congruent practices and provide opportunities for everyone to acknowledge and reflect on conflicts in their values and practices.

But providing opportunities to reflect on potential moral transgressions is ineffective without training and education related to recognizing and navigating unavoidable moral challenges. Mentorship in these regards is essential, as is support for staff who are exposed to moral risks, which is where a values-based framework of corporate culture proves critical. Rather than compliance-based frameworks that seek to prevent or to root out (and usually punish) misconduct, values-based frameworks seek to shape and enable professional conduct. To that end, disciplinary processes are fair, open, visible, honest, consistent, equitable, and just. The organization provides support and repair-focused strategies for those who have transgressed.

A morally healthy organization approaches potentially transgressive situations with courage and curiosity rather than avoidance, blame, or shunning. Challenges from within the organization to sources of moral transgression are welcome, if uncomfortable. And the organization, situated in a complex sociopolitical ecosystem, has an obligation to speak out in defense of its workforce against potential regulatory or legislative sources of moral injury, valuing moral justness more than simple adherence to regulation and legislation.

The Moral Imperative of High Resource Utilization

The outermost circle in the ecological model of moral injury is the sociopolitical environment of policy, politics, values, priorities, economics, and will. Healthcare organizations and systems must acknowledge the influence they exert on the communities they serve, and whose resources sustain them. Healthcare consumes 17.3 percent of the US gross domestic product, or slightly more than one-sixth of the economy,18 which is more than five times US defense spending.19 Even the smallest healthcare megaproviders, in 2017, had revenue greater than Fox News, CNBC, and MSNBC combined.20 In 2020, health firms spent a total of $713.6 million on lobbying. Pharmaceutical and health product manufacturers spent the most ($308.4 million), followed by providers like health systems, hospitals, and clinics ($286.9 million), insurers ($80.6 million), and others ($37.7 million).21 The economic power of the healthcare sector is staggering. As Dr. Berwick wrote, “The cycle is vicious: unchecked greed concentrates wealth, wealth concentrates political power, and political power blocks constraints on greed.”22 Healthcare spending remains high (with a low return on investment when the United States is compared with other wealthy countries23), and far too little is spent on factors that have a strong impact on communities’ health and well-being: housing and food insecurity, social services, public safety, education, job training, and criminal justice reform. It is unconscionable that these huge healthcare institutions, which capture so much of our economy as to crowd out other needy sectors, should remain silent and sidelined on issues of moral consequence for their patients and their workforces.

Bargaining Morality

Although it will be challenging to make morally centered organizations the norm in healthcare—and pressure to change will need to come from many sources, including communities and legislators—unions have a major role to play in advancing moral practices. How does one translate these research findings into negotiations at the bargaining table? The following points may be useful to consider or adapt.

- The organization must conduct audits of key performance metrics related to staff experience such as turnover, retention and exit interviews, absenteeism, and job satisfaction. Whether or not the organization conducts such audits, the union should also conduct retention and exit interviews and gather information on job satisfaction.

- Provide yearly updates to action plans addressing the findings, in collaboration with workforce representatives.

- The organization must invest in measuring not only burnout, but moral injury.24 The results must be shared with the workforce in a timely way. With or without the organization’s support, the union can also measure burnout and moral injury, sharing its findings with staff and management.

- Risk and management strategies for moral injury must be communicated freely with the workforce and must be informed by input from practicing clinicians.

- Related to moral injury is physical and psychological safety. The organization must measure and commit to researching the physical and psychological safety of the workforce, also sharing results in a timely way. Again, the union can do this with or without the organization’s help.

- As an extension of psychological safety, and to ensure whistleblowers have recourse in the event of retaliation, a disinterested third party should be engaged to inquire about whistleblower experiences when speaking up.

- The organization must ensure adequate mechanisms are in place to empower workers at all levels to discuss moral and ethical dilemmas in the workplace.

- The union may want to establish a committee to determine what mechanisms make the workforce comfortable with such discussions, then bring its recommendations to management.

- Processes for developing solutions to prevent avoidable risks of moral injury and mitigate unavoidable risks must have meaningful engagement from all levels of the workforce (e.g., through labor-management partnerships or other similar mechanisms). Such solutions development must be appropriately resourced to support strategy development, implementation, and sustainment.

+++

Health worker distress was a crisis before the coronavirus pandemic, and it has only intensified since. None of the myriad interventions to help individual workers address their experiences have made a substantial impact on workers’ mental health and well-being, despite health systems collectively pouring millions of dollars into them. It is time for two new approaches: first, to expand the definition of clinician distress to include the relational ruptures of moral injury, and secondly, to begin holding health systems responsible for the environments they create. Again, quoting Dr. Berwick, “The source of what the philosopher Immanuel Kant called ‘the moral law within’ may be mysterious, but its role in the social order is not. In any nation short of dictatorship some form of moral compact, implicit or explicit, should be the basis of a just society.”25 And the basis of the institutions where we are promised to heal.

Wendy Dean, MD, is a psychiatrist and cofounder of Moral Injury of Healthcare. She has published widely on clinician distress and its impact on patient care and is the author, with Simon Talbot, of If I Betray These Words: Moral Injury in Medicine and Why It’s So Hard for Clinicians to Put Patients First. The primary study referenced in this article was a collaboration with Deborah Morris, PhD, and her team at St. Andrew’s Healthcare in Northamptonshire, England, for which the author is deeply grateful. No outside funding supported the work.

*AFT Health Care has published several articles on moral injury documenting the challenges healthcare workers face and how to address them; see aft.org/hc/subject-index#moral-injury. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. S. Talbot and W. Dean, “Physicians Aren’t ‘Burning Out.’ They’re Suffering from Moral Injury,” STAT, First Opinion, July 26, 2018, statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury.

2. S. Mantri et al., “Identifying Moral Injury in Healthcare Professionals: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-HP,” Journal of Religion and Health 59, no. 5 (October 2020): 2323–40.

3. S. Rabin et al., “Moral Injuries in Healthcare Workers: What Causes Them and What to Do About Them?,” Journal of Healthcare Leadership 15 (August 2023): 153–60.

4. D. Ofri, “The Business of Health Care Depends on Exploiting Doctors and Nurses,” New York Times, June 8, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/06/08/opinion/sunday/hospitals-doctors-nurses-burnout.html.

5. D. Berwick, “The Moral Determinants of Health,” Journal of the American Medical Association 324, no. 3 (2020): 225–26.

6. F. Lateef, “Patient Expectations and the Paradigm Shift of Care in Emergency Medicine,” Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 4, no. 2 (April 2011): 163–7.

7. J. Beauge, “UPMC Susquehanna Says It Can’t Be Sued for Fraud over ‘Puffery’ Phrases in Advertisements,” PennLive, October 4, 2020, pennlive.com/news/2020/10/upmc-susquehanna-says-it-cant-be-sued-for-fraud-over-puffery-phrases-in-advertisements.html.

8. Federal Trade Commission, “Non-Compete Clause Rulemaking,” January 5, 2023, ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/federal-register-notices/non-compete-clause-rulemaking.

9. Government Accountability Office, Noncompete Agreements: Use Is Widespread to Protect Business’ Stated Interests, Restricts Job Mobility, and May Affect Wages (Washington, DC: May 2023), GAO report 23-103785, gao.gov/assets/gao-23-103785.pdf.

10. A. Vance, “It’s a TRAP! Labor Board Seeks to Prohibit Use of Training Repayment Agreement Provisions,” National Law Review, October 12, 2023, natlawreview.com/article/its-trap-labor-board-seeks-prohibit-use-training-repayment-agreement-provisions#google_vignette.

11. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Request for Information Regarding Employer-Driven Debt,” Federal Register, June 17, 2022, federalregister.gov/documents/2022/06/17/2022-13030/request-for-information-regarding-employer-driven-debt.

12. D. Bartz, “More U.S. Companies Charging Employees for Job Training If They Quit,” Reuters, October 17, 2022, reuters.com/world/us/more-us-companies-charging-employees-job-training-if-they-quit-2022-10-17.

13. J. Nigam et al., “Vital Signs: Health Worker–Perceived Working Conditions and Symptoms of Poor Mental Health—Quality of Worklife Survey, United States, 2018–2022,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72, no. 44 (November 3, 2023): 1197–1205.

14. D. Amsalem et al., “Psychiatric Symptoms and Moral Injury Among US Healthcare Workers in the COVID-19 Era,” BMC Psychiatry 21 (2021).

15. Mantri et al., “Identifying Moral Injury.”

16. D. J. Morris, E. L. Webb, W. Dean, J. Wainwright, R. Hampden, and S. Talbot, “Guidance for Creating Morally Centred Organisations That Remediate the Experience of Moral Injury in Healthcare: Findings from an International E-Delphi Study,” manuscript in preparation.

17. H. Gardner and L. Shulman, “The Professions in America Today,” Dædalus 134, no. 3 (Summer 2005): 13–18, amacad.org/publication/professions-america-today.

18. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “NHE Fact Sheet,” December 13, 2023, cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet.

19. World Bank, “Military Expenditure (% of GDP),” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS.

20. D. Dranove and L. Burns, Big Med: Megaproviders and the High Cost of Health Care in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021).

21. W. Schpero et al., “Lobbying Expenditures in the US Health Care Sector, 2000–2020,” Journal of the American Medical Association Health Forum 3, no. 10 (October 2022): e223801.

22. D. Berwick, “Salve Lucrum: The Existential Threat of Greed in US Health Care,” Journal of the American Medical Association 329, no. 8 (2023): 629–30.

23. R. Derlet, “Bedside Medicine to Corporate Medicine,” AFT Health Care 4, no. 1 (Spring 2023): 16–22, aft.org/hc/spring2023/derlet.

24. Berwick, “The Moral Determinants of Health.”

25. W. Dean et al., “Moral Injury in Health Care: A Unified Definition and Its Relationship to Burnout,” Federal Practitioner 41, no. 4 (April 2024): 104–7.

[Illustrations by Isabel Espanol]