J was an African American child residing in an impoverished community on the South Side of Chicago. Her parents and her grandparents had less than a high school education. J’s mother was unemployed and suffered from a mental illness, so she was sometimes institutionalized. J never really knew her father. She also never really knew that she was born into poverty, although she and her sibling lived in substandard housing with grandparents with limited education and income, struggling to survive. Families in the surrounding low-income neighborhoods were struggling as well.

J attended elementary school, but her world began to unravel when both of her grandparents died. The lack of support and resources to attend school led J to drop out during the seventh grade. She didn’t have health insurance. The family had access to healthcare at the local county hospital, but J did not have a primary care provider or pediatrician to guide her healthcare during her developing years, so she didn’t have access to ongoing wellness or health promotion education.

J lived in a neighborhood without access to affordable fruits and vegetables and experienced many years of eating unhealthy fast foods, which brought with them the increased risk of chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and even cancer—all of which disproportionately affect African Americans. J also recalled a brief period of food insecurity. When her family fell on hard times, she even experienced a short bout of homelessness. After her mother was deemed unfit for parenting and they were evicted from her family’s apartment, J was placed into foster care at age 11.

+++

J’s story is all too familiar for many families across our country today. I often tell it at the beginning of a presentation I give to nurses about the social determinants of health—the social and economic factors that are known to influence the health and longevity of individuals and communities at large. Born to poor parents, J was already at risk for a number of health disparities and inequities. Childhood poverty remains a significant predictor of future poverty status, and African American children are among those hardest hit. We know that poverty limits access to healthy foods and safe neighborhoods. We also know that in communities with unstable housing, low-income and unsafe neighborhoods, substandard education, low health literacy, and lack of access to healthcare, health outcomes are strikingly poor.1

We all are impacted by the social determinants of health: those social, economic, and even political factors that influence our lives, our environments, our resources, where we live, where we work, and more. Those factors can impact the health and well-being of patients and communities in positive and negative ways. Before I continue with the story of J, I’d like to explore the relationship between determinants and health outcomes, describe some of the progress in addressing the adverse impacts of the social determinants of health, and consider the implications for nursing practice, research, and education and advocacy.

Defining Our Terms

We can’t talk about the determinants of health without talking about health equity and vice versa—but it’s important to understand the difference between them. When we talk about health equity, we mean that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible, which requires that we remove the obstacles to those opportunities: poverty, discrimination, and their consequences; powerlessness; and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education, adequate housing, safe environments, and healthcare. Working for health equity includes a focus on those conditions that drive health inequities, particularly among our underserved, under-resourced, marginalized, and otherwise excluded populations.

The National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) defines health disparities as racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare treatment that are not due to what we normally might expect: they’re not caused by access factors, clinical needs, patient preferences, or even what we do as an intervention.2 Health disparities are similar to health inequities in that both mean differences in the presence of disease, health outcomes, or access to healthcare between population groups. But unavoidability is central to the definition. Some people experience health disparities because of policies and practices they cannot avoid.

Health equity and health disparities are closely related. Health equity embodies the ethical and human rights principle. It’s the value that motivates us to eliminate health disparities or to focus on key determinants of health like education, housing, and discrimination. Without addressing some of these variables that drive health disparities, we will never achieve health equity. Determining the presence of, absence of, or decrease in health disparities are some of the ways we can measure how much progress we’re making toward achieving health equity.

It’s also important to work from a shared understanding of the social determinants of health. One common framework from the World Health Organization describes the social determinants of health as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age.”3 Those social, economic, and political factors that influence where we live and what we have access to are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at local, state, and global levels. We see the truth of this every single day. Some communities have more resources than others, buoyed by economics, policies, systems, and environments. Certain communities are struggling with environmental toxins and pollutants,* while others have different regulations and policies that drive their access to a safe and clean environment.

We’re talking about the social determinants of health because we are finally recognizing that while excellent healthcare is very important, it’s not enough. Even with the amount of money that we spend on healthcare in the United States, we are lagging behind in some key indicators.4 We’re far behind some other countries in maternal health outcomes, even though we have experts and state-of-the-art technology and facilities.5 Our life expectancy is lower than comparable countries.6 Medical care is insufficient for ensuring better health.

Understanding Health Outcomes

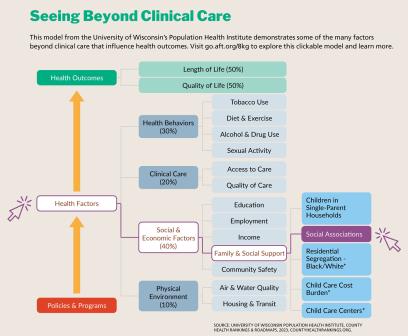

The social determinants of health have a lot more to do with life expectancy and quality of life than we might expect. According to population health researchers at the University of Wisconsin, only 20 percent of individual health outcomes are related to clinical care, including access to care and quality of care.7 (See the graphic below for more details.) As providers of care, we are all striving to give our patients the best clinical care, which is very important—but perhaps it’s time to ask what else we could do.

Individual health behaviors—such as diet and exercise, tobacco use, alcohol and drug use, and sexual activity—account for about 30 percent of a person’s health outcomes. On the other hand, about 40 percent of a person’s health outcomes are directly tied to social and economic factors, including education, employment, income, family and social support, and community safety. And, of course, these factors are interrelated. Individuals with a higher level of education are more likely to have jobs that pay a livable wage and therefore are more likely to have health insurance. Individuals with higher-paying jobs have more money to take care of basic needs like food and housing. Individuals with family and social support may be more likely to engage in health-promoting activities because they have the help they need to get to and from a doctor’s appointment or someone in their lives who is nudging them to take better care of themselves. And individuals who live in environments where they can walk freely spend time outside, getting fresh air and exercise.

The physical environment also accounts for about 10 percent of an individual’s health outcomes. Poor air quality and poor water quality are not just problems in developing countries; we have these issues in our own backyards. In certain areas of the West Side and the far South Side of Chicago, for example, there are higher rates of asthma8 among our children because those neighborhoods are surrounded by refineries and other sources of air pollution. The quality of available housing and transportation is also important. How can we expect anyone to thrive or to experience optimal health while living in rat-infested or lead-contaminated dwellings? And do we have access to the transportation we need to get to and from our appointments and our jobs, or to just go about our daily lives?

All of these factors influence health outcomes, and they’re all connected, primarily centered in where a person lives. The neighborhood you live in determines

- how much money your community has to invest in schools, libraries, and other resources;

- how easily you can access primary care providers, healthy foods, safe and sanitary housing, and other necessities for health;

- the safety and walkability of your community;

- the availability of reliable, affordable public transportation;

- the degree of racial and ethnic segregation; and

- the quality of the air you breathe and the water you drink and use to shower, cook, wash your clothes, and brush your teeth.

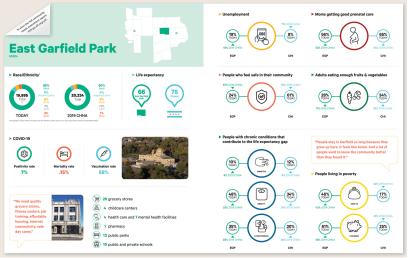

Here’s one powerful example: individuals who live in the downtown Chicago area have a life expectancy of about 85 years.9 Compared with the rest of Chicago, they tend to have higher incomes, better jobs, higher levels of education, and better access to community resources and healthcare providers. They are mostly white.10 But just a few stops away by public transit is a majority Black neighborhood called East Garfield Park, where the life expectancy decreases to about 66 years.11 Those individuals have far fewer resources. Fewer residents have completed college, and they tend to have poor health literacy. Many live in substandard housing and don’t make a livable wage.12 It’s no wonder that their life expectancy is not the same as those who reside in a much more affluent area of the city. (To learn more about East Garfield Park, see the excerpt of the 2022 community health needs assessment by Rush University Medical Center and Rush Oak Park Hospital below.)

When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, everyone talked about its disproportionate impact on communities of color across our country; these communities suffered the greatest burden of disease and poor outcomes. Many individuals had public-facing jobs and didn’t have the luxury of working remotely. Some were living in very crowded housing situations with increased exposure to and risk of contracting the virus. But as the example above shows, communities of color have long had adverse health outcomes and experienced these living conditions even before the pandemic. COVID-19 just unveiled these underlying inequities.13

Many healthcare institutions, insurers, and other stakeholders are now turning to these critical issues. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now requires hospitals to start screening some of their patients for the determinants of health, and community-based healthcare centers are following suit. They’re asking questions like

- Do you currently have a place to live or stay? In the next two months, will you have a place to live or stay?

- Are you worried that your food will run out before you have money to buy more? In the last two months, have you run out of food that you bought and did not have money to get more?

There was a time when we didn’t ask these types of assessment questions. But that’s beginning to change as more people come to understand the importance of the social determinants of health. For example, while some health systems are working with local restaurants and convenience stores to make sure that residents have access to healthy food, others are developing safe and affordable housing. These institutions are taking on this work because they’re starting to ask themselves, “What can we do to improve health outcomes and broaden our lens beyond clinical care to address unmet social needs?”

Moving Beyond the Essentials

Once we understand the roles these factors play, we have to start looking at the influence of policy. What are the political determinants that define whether we can achieve health equity? As clinicians, we can provide care at the point of illness, and we can offer interventions on an individual level when we screen patients and coordinate services with social workers and case managers. But the real impact comes when we address community needs and try to prevent harm from occurring by taking a critical look at the laws, policies, and regulations that can have such a dramatic impact on overall community conditions. With an equity lens, we can ask questions like: What do those laws, policies, and regulations say? Who benefits from them? Who might be adversely impacted by them? Who was at the table to help create them? That’s where the rubber really meets the road.

Recognizing the Political Determinants of Health

If we are serious about eliminating health disparities, we have to get to the root of the problems that create them—what have been described as the political determinants of health.14 We can’t talk about food security unless we talk about food deserts, areas with limited access to a variety of affordable healthy foods.15 We can’t advance health equity if we overlook people who are unhoused or living in substandard housing or who don’t have jobs that provide a living wage. Only by understanding these determinants, their origins, and their impact on equitable distribution of opportunities and resources will we be able to close the healthcare gap.

When we think about changing policies, most of us probably think about federal policy, but we don’t all have to go to Capitol Hill to make a difference. What happens on the federal level does impact what happens at state and local levels, but we can use our health expertise much closer to home to advocate for policies that will improve health outcomes. In Illinois, for example, the Health Care and Human Services Reform Act, signed into law in 2021, focuses on improving health equity and the health and well-being of Illinois residents.16 There are many more opportunities at the state, city, and local levels, and all of us who work in healthcare can make valuable contributions by sharing our expertise.

Taking Action: What We Can Do

We have made some advances in the movement toward health equity. There is increased awareness about the determinants of health, more integration of this content into our nursing educational programs, and movement in healthcare institutions, the insurance industry, and the policy arena. But the determinants of health are just one steppingstone to achieving health equity, and we all have a part to play.

A 2021 report, The Future of Nursing 2020–2030,17 talks about the invaluable role of nurses and nursing in achieving health equity. It discusses what we as a profession need to do and what we can work on in our everyday practice as we strive to provide all our patients with affordable, equitable, and quality care. It’s not just about access to care. We also have to make sure that our care is culturally relevant and addresses the individual needs of each patient. Once a patient overcomes the hurdle of accessing care, they may face additional struggles: Do they always understand what’s going on with their care? Do they feel empowered and trust providers and others enough to ask the questions they need answered? Our patients face these struggles every day. And we as health professionals can unwittingly make these problems worse—or we can fight to make them better.

Making them better requires that we take a good hard look at ourselves. As you begin to consider what role you might play, pause for a few moments to think about these questions.

- To what extent do your employer, your local union, your state federation, and other specialty organizations you may be involved with address the determinants of health?

- Are you, as a health professional or a leader, able to take these variables into account in your daily nursing practice?

- What can your organization, your profession or specialty, or your voluntary organizations do in partnership with others to advance health equity?

- What other partners are needed to improve the health outcomes of those we serve?

Health professionals can’t do this work alone. There is an African proverb that says, “When spiderwebs unite, they can tie up a lion.” That just means this is an all-hands-on-deck effort. We will need to join with many other partners to advance health equity, including community-based organizations, faith communities, elected officials, and others also engaged in advancing health equity whom many of us may not have considered before.

Building Effective Partnerships

What can we do in our communities? No matter where we sit or work, we want to make sure that the decision-making body reflects the composition of the populations or constituents we serve. Partnerships are critical in this effort.

Establish a roundtable discussion. You might consider establishing regular discussions about equity issues to stimulate dialogue around what it means to have inequitable access or to experience inequities. Such a discussion could include not only clinicians from multiple disciplines and specialties but everyone who has a stake in the game—e.g., consumers, patients, and elected officials—to describe and discuss these issues and come up with solutions. In these conversations, community perspectives and input should be at the center. In community-based participatory research,† we are trying to engage communities in shaping a research agenda, and the same thing applies to advancing health equity. We need to bring our communities on board, not only to hear what some of the issues are but also to identify some of the solutions, which should be driven by community members’ lived experiences and input.

Analyze policies using an equity lens. There are equity assessment tools emerging now that can help us consider who’s benefiting from policies being proposed or enacted. What are the burdens of the policy? Is one policy going to be more burdensome or detrimental for any groups, particularly any underserved populations? These kinds of assessments look at both narratives and numbers. Paraphrasing Sir Austin Bradford Hill,18 a pioneer of epidemiology, African American cancer surgeon Dr. Harold Freeman once said, “Statistics are just the numbers with the tears washed away.”‡ Statistics are essential, but so are the stories from people who are living every day with these poor environments, poor living conditions, and poor odds of good health.

Attend implicit bias and other anti-racist training. In the state of Illinois, we now have a law that all our healthcare providers must have implicit bias training because we know that some of our patients and communities are still facing racism. They’re not always welcomed when they come to our facilities. Healthcare providers aren’t always sensitive to the conditions they live in or to that lived experience. A recent report from the National Commission to Address Racism in Nursing revealed that there’s a lot of racism in the nursing profession that undermines the good work we’re doing.19 We need to take a step back and assess how we might be further perpetuating these disparities.

Incorporate a community needs assessment into your nursing endeavors. Your employer or other organizations in your community may be required to conduct community health needs assessments. The Affordable Care Act requires that all healthcare organizations that claim tax-exempt status conduct and make public a community health needs assessment and implementation plan every three years. These assessments can provide key information to health professionals, as the example from the Rush University System for Health shows. If I were a nurse working in East Garfield Park, for instance, it would be important for me to know that there is a decreased life expectancy in this community. There are no high-quality, affordable grocery stores or food markets,20 so if my patients are coming into the hospital malnourished or underfed, that could be due to the variety or affordability of the foods they have access to. I would also see that there are few community-based health centers or mental health centers. There are a lot of public and private schools in this community, but what is the quality of those schools? All of this is helpful information.

In my experience, community health needs assessments tend to be underutilized. They can inform us about where our patients are coming from and what they’re living with day to day. They can also help us plan programming and outreach activities that we believe will meet our patients’ needs. If your employer or local hospital doesn’t produce needs assessments, you can also get helpful data from your city, county, or state health department or from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov).

Imagining a Brighter Future

When I give this presentation to nurses, at this point I ask them to return to the story of J. I ask what they think might have happened to her, based on the information they have about the circumstances of her young life—and here I ask you to do the same. Spend a few moments pondering, and perhaps jot down a few notes in the margin about where you think J might have ended up.

Attendees often suggest that the cycle of poverty continued, that J became pregnant as a teenager and had several children, or that she began using drugs, experienced extended homelessness, or had her own mental health struggles. All of these guesses are reasonable based on what we know about people who have had similar experiences.

But I then ask them to imagine what could happen if we changed the script.

Imagine J born into poverty—but somewhere along her journey to adulthood, she received support to finish her education instead of dropping out in seventh grade. Imagine she received financial support to complete her college education, allowing her to secure meaningful employment with benefits and an hourly wage that started at double the minimum wage. She could now afford stable housing, and she had insurance because her employers provided healthcare coverage.

J’s health literacy skills greatly improved because she was able to complete her high school education, which exposed her to more health-related resources and information. She also had a regular primary care clinician who provided lifesaving health information. Her nutritional status improved because once she knew better, she could do better, but also because she had the means to buy more nutritious foods instead of relying exclusively on fast food. Her chances of living a long and healthy life improved because her social and economic status improved.

Today, J attributes these changes to the strong social support she received, particularly from her social worker during her junior year in high school. She feels blessed to have beaten the odds and to have overcome the myriad issues that we know lead to disparities for many children born into poverty. Resiliency was an important factor in improving J’s outcome, but it wasn’t the only factor. She experienced a positive change in the social and economic factors that can adversely influence the health status and health outcomes of any child, any adult, and any community over time.

Education was probably the most powerful determinant of health for J. As discussed earlier, education can influence the opportunity to even get a job, let alone a good one with benefits and insurance. And the higher the level of education, the more likely we are to know more things, to have access to resources, to understand those resources, to navigate the system, and to have a higher degree of health literacy. Demonstrating the importance of political determinants of health, J was only able to get funding to go to college because of a state initiative that provided scholarships to children in foster care. Hers could have been a different narrative, but J met someone along her journey to adulthood who helped to shape and change that narrative and produce a more positive outcome.

Telling a New Story

What I don’t usually tell attendees is that I know so much about J’s story because J is me. We live in the land of plenty, where each person is supposed to have the same opportunities to work hard and succeed, but for far too many children in the United States, that is a myth. Only an estimated 3 to 10 percent of foster youth even finish college, and the numbers for high school graduation also lag far behind other students.21 We hear that narrative pretty often—but we don’t hear about those who do succeed against the odds. Their stories—our stories—have a lot to teach us, too.

It may not make sense to some people, but in some ways I’m grateful for my childhood experiences because I don’t think I would have had access to a social worker who was committed to young people had I been in different circumstances. Without her, I probably would still have lived the typical narrative: dropped out of school, gotten evicted, perhaps even struggled with mental illness. From my perspective, that’s a very dim outlook. But then, this social worker appeared in my life, picked me up, and said, “I think you’ve got some potential. Let me work with you.”

Our world—and our patients—need more people like that social worker: someone who was passionate about their job and cared enough not only for me but for so many others to help make a difference in our lives.

I received state funding to go to college, and I also worked a few campus jobs to get some extra spending money. I entered the nursing program, which was very challenging. Even though I was a good student in high school, in college I was competing with kids from all over the globe who came from better schools, including private schools. It took me two solid years to get into the groove of being a college student. I had to learn how to study. I loved learning how the body worked, but I didn’t like bacteriology or any of the more abstract prerequisite courses. But even though those first few years were hard, I was driven to complete the program because I knew I didn’t have much of another option. I had to stay in school, try to get some support from college administrators (which I was blessed to receive), and get out and do something with myself. I knew that I couldn’t go back to where I was. That was my driving force.

I finished college and went on to get a great job at the University of Chicago making $5.65 an hour, which at that time was more than double the minimum wage. That was a lot of money for someone just out of college in the mid-1970s. It was enough to rent an affordable apartment in a safe neighborhood, buy nutritious foods, and take care of my other basic necessities.

I eventually decided to go back to school for a master’s degree because my medical center offered 100 percent tuition reimbursement. It’s hard to say no to that type of resource. When I graduated and started doing my community work, I fell in love with public health concepts and became fascinated with health disparities work. That’s when I decided to go back to school for a PhD in nursing, and that research led me to places I never imagined. I studied adherence to breast cancer screening guidelines among low- and middle-income Black women, and teachers were my sample of Black women with middle income. Because of that work I met Barbara Van Blake, the former director of the Human Rights and Community Relations Department at the AFT; working as a consultant for the AFT, I traveled the country with Barbara doing breast cancer education.

Since then, I’ve been blessed to travel the globe. I’ve been invited to present my work on disparities and other equity issues on every continent except Antarctica. (I don’t know of any conferences there, but if I’m invited, I’ll go.) And I find time to write books and articles because I feel that’s what I should be doing as a woman with a PhD.

I’m passionate about equity issues, and I’ve met great people and worked with great colleagues and partners along the way to address these issues. In my new role as the assistant director of the Illinois Department of Public Health, I’m excited to address health equity across the state.

When I started this journey, I had no vision, no clue, no road map. But somehow, I found guides. We often talk about mentors, but there are also models. Not everybody can be a mentor, but there are a lot of people who modeled the behaviors that I wanted to emulate. I’ve learned a lot just from watching, reading about, and hearing from these people. They probably don’t even know how they’ve impacted my trajectory, but I have them to thank.

Most nurses attending my presentation expect J’s story to end in tragedy. Very few suggest positive outcomes. But I don’t tell them that J is telling the story because I want them to understand that J could be anyone. I hope they’ll think about J when they encounter patients and other people they don’t know. I hope they’ll consider J before having unkind thoughts or making stereotypical remarks about people. None of us knows the road another person has traveled—or what potential they hold.

Once, I was walking the University of Illinois campus and someone I didn’t know came up to me and told me I was the reason they went back to school. I asked why, and they said, “I’ve always watched you, and you really have inspired me.” We never know who’s watching us. We never know how our words or actions or the way we treat people might inspire someone, give them the hope of doing something more.

Not everybody is going to go to college, but every job—no matter what it is—is important because it helps advance society or keep it running. We want everyone to at least have a decent life, no matter their chosen vocation. And we definitely want people to experience better health. Breaking down those barriers that we know prevent people from achieving better outcomes—that’s part of our mission as health professionals.

Janice Phillips, PhD, RN, CENP, FAAN, is the assistant director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. She was previously the director of nursing research and health equity at Rush University Medical Center and an associate professor in the College of Nursing.

*For details on environmental toxins, and environmental racism, see “Healing a Poisoned World” in the Fall 2020 issue of AFT Health Care. (return to article)

†For examples of community-based participatory research, see “Brave Spaces” in the Fall 2021 issue of AFT Health Care and “Environmental Justice” in the Spring 2022 issue. (return to article)

‡Dr. Freeman said this during a talk on poverty and cancer many years ago, and I have carried it with me ever since. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, “Healthy People 2030: Social Determinants of Health,” US Department of Health and Human Services, health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health.

2. B. Smedley, A. Stith, and A. Nelson, eds., Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003), 32.

3. World Health Organization, “Social Determinants of Health,” United Nations, who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

4. R. Derlet, “Bedside Medicine to Corporate Medicine: How Working Americans Have Paid the Price,” AFT Health Care 4, no. 1 (Spring 2023): 16–22; and J. Kitzhaber, “COVID-19: From Public Health Crisis to Healthcare Evolution,” AFT Health Care 1, no. 1 (Fall 2020): 6–15, 44.

5. J. Taylor, “The Importance of Respectful Maternity Care for Women of Color,” AFT Health Care 2, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 20–23, 39.

6. D. Radley et al., “Americans, No Matter the State They Live in, Die Younger Than People in Many Other Countries,” blog, Commonwealth Fund, August 11, 2022, commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/americans-no-matter-state-they-live-die-younger-people-many-other-countries.

7. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, “County Health Rankings Model,” University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/county-health-rankings-model.

8. South Side Pediatric Asthma Center, “Who We Are,” University of Chicago Medicine, southsidekidsasthma.org/who-we-are; and S. Guy, “Chicago Hospitals Form Partnership to Battle Asthma ‘Hot Spots,’” Chicago Sun-Times, May 9, 2018.

9. M. Gamble, “The Physician CEO Keeping It Real for RUSH and Chicago,” Becker’s Hospital Review, June 1, 2023, beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/the-physician-ceo-keeping-it-real-for-rush-and-chicago.html.

10. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “The Loop: Community Data Snapshot,” Chicago Community Area Series, July 2023, cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/126764/The+Loop.pdf.

11. J. Andrews et al., Stronger Together: Advancing Equity for All; A Community Health Needs Report and Action Plan: FY2022 CHNA + FY2023–2025 CHIP (Chicago: Rush University Medical Center and Rush Oak Park Hospital, 2022), rush.edu/sites/default/files/chna-chip-2022.pdf.

12. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, “East Garfield Park: Community Data Snapshot,” Chicago Community Area Series, July 2023, cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/126764/East+Garfield+Park.pdf.

13. J. Phillips, “COVID-19: Another SOS Call from Communities of Color,” The Hill, April 19, 2020, thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/493536-covid-19-another-sos-call-from-communities-of-color.

14. D. Dawes, The Political Determinants of Health (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, March 24, 2020).

15. P. Dutko, M. Ver Ploeg, and T. Farrigan, Characteristics and Influential Factors in Food Deserts, Economic Research Report Number 140 (Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, August 2012), ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/45014/30940_err140.pdf.

16. “Governor Pritzker Signs Equity Driven Healthcare Reform Legislation,” press release, April 27, 2021, illinois.gov/news/press-release.23204.html.

17. M. Wakefield et al., eds., The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2021), nam.edu/publications/the-future-of-nursing-2020-2030.

18. Kerr White Healthcare Collection, “Health Statistics and Epidemiology,” University of Virginia, 2006, historical.hsl.virginia.edu/kerr/healthstats.cfm.html.

19. National Commission to Address Racism in Nursing, Racism in Nursing (Washington, DC: American Nurses Association, May 1, 2022), nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/racism-in-nursing/national-commission-to-address-racism-in-nursing/commissions-foundational-report-on-racism--in-nursing.

20. Breakthrough, “The Fresh Market Meets Needs During COVID-19 Pandemic,” August 25, 2020, breakthrough.org/fresh-market-meets-needs.

21. J. Geiger and R. Johnson, “Expanding Our Understanding of Student Experiences and the Supports and Programs for College Students with Foster Care Experience: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Foster Care and Higher Education,” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 40 (2023): 159–61.

22. J. Phillips et al., “Integrating the Social Determinants of Health into Nursing Practice: Nurses’ Perspectives,” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 52, no. 5 (September 2020): 497–505.

[illustrations: Stephanie Dalton Cowan]