Growing up, my social studies experiences were not great. To be frank, the subject was boring. We read dense chapters in textbooks, we answered a set of questions at the end of each of those dense chapters, we listened to droning lectures about historical topics, we temporarily memorized dates and facts the teacher deemed important, we took a test, and then we repeated this same cycle. Absent were peer-to-peer collaboration, making connections, discussions, and genuine engagement and interest. If you ask what I remember learning in those classes throughout the years, I guess it would be that I got a perfect score on a state-mandated eleventh-grade US history test, but I don’t remember much of anything about the content I learned or why it mattered.

So it’s no surprise that I didn’t understand the value of social studies. I didn’t see any purpose for my history classes other than as a means to move on to the next grade and eventually graduate from high school. I didn’t feel any personal connection to the social studies content or see my identity as a Black child included much in those classes.

When I started teaching in 2008 in Jackson, Mississippi, I chose to be a middle school English teacher. In my mind, English was one of the more interesting subjects because it was filled with reading texts from different time periods and genres; plus, it meant I got to be engaged in teaching students how to write and discuss their ideas. Fast forward 10 years: I was teaching in Baltimore City Public Schools when, due to some staff changes at my school, I had to teach both seventh- and eighth-grade English and eighth-grade US history. I was terrified. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I had flashbacks to how bored and disconnected I’d felt in my history classes.

Once I started teaching that social studies class, I dug into various historical topics through research and reading. I finally saw the deep layers and perspectives that went well beyond the cookie-cutter approach to teaching history from a Eurocentric perspective. Not only that, students had so many questions and connections that they wanted to make. There was this big shift within me. I never thought I would see the day, but I actually preferred teaching history over English. In 2019, I decided to teach only sixth- through eighth-grade social studies. And in 2022, I transitioned into a teacher leadership role as an educational associate for kindergarten through eighth-grade social studies at my school so that I could strengthen the social studies program.

It’s amazing to see the students at my school and throughout my district have very different experiences with social studies than I had. Recently, while walking down the hall on my way to a meeting space, a fourth-grader saw me and smiled big: “Mrs. Thomas, let’s go! We have you for social studies today!” I was happy to hear that student’s excitement for social studies class, and it made me consider what it was about the way I taught social studies that made students excited to learn about the past.

It’s clear to me that recalling dates and events hasn’t inspired students to learn about or enjoy history. Neither has omitting difficult historical topics such as slavery and land theft or having the teacher sit up front imparting information that must be copied down. It wasn’t until I began teaching social studies that I saw the valuable gift it is. To me, that enthusiasm for and internalization of social studies happens when students are given the chance to use their natural curiosity to learn by questioning, discovering, finding answers, and making connections—especially to their lives. I avoid recall and drill tasks; instead, I look for ways students can experience and use social studies to make meaning of the world around them and discover the value of history in their lives.

Xavier, a student at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, captured that value. In a news article about the new Advanced Placement African American Studies course—which has been attacked by those who see teaching facts about race and racism as controversial—Xavier showed that such courses are essential, saying, “I don’t think you can go through life without knowing your history. You wind up feeling lost or unsure of yourself. It’s harder to form an identity.”1 That quote really connected with me because it captured why I never really liked my social studies classes throughout my school years. I wasn’t given the chance to know my history as a Black kid and how that fit into the fabric of American history. Knowing your history and understanding your identity are key to being invested in social studies. This is why there is a need for culturally diverse, inquiry-driven history lessons in which certain voices aren’t omitted or ignored. This allows all students to see themselves and learn about others—and leads to deeper connections and understandings.

Launching BMore Me

Wanting to ensure that all students in Baltimore City Public Schools become invested in social studies, the district brought together a coalition of teachers to create a new curriculum called BMore Me. BMore Me immerses students in inquiry-based learning about their history and strengthens their understanding of their identities and power. It has students grappling with history topics that are state mandated but also specific to Baltimore and the state of Maryland. The ultimate goal is for students to feel sure about their identities and their history locally, statewide, and nationally.

Baltimore City Public Schools introduced BMore Me for sixth- through eleventh-grade students in 2019. The BMore Me curriculum started off with three weeks of social studies lessons designed to immerse students in learning about the rich history of Baltimore, as well as the state of Maryland, so that students could tell their stories and become leaders and thinkers in their schools and communities.

The creation and launch of BMore Me didn’t happen magically. A key factor was that Baltimore City Public Schools made sure that a former Baltimore teacher, Christina Ross, managed the program so that it stayed true to the original vision. Another was that instead of hiring people who were not in the classroom, BMore Me hired teachers as paid summer fellows to be trained about the process and to write the curriculum units. At the time, the district’s goal was to create one two-week-long, optional BMore Me unit for each sixth- through eleventh-grade band that could easily be integrated into social studies classes at least once in the year.

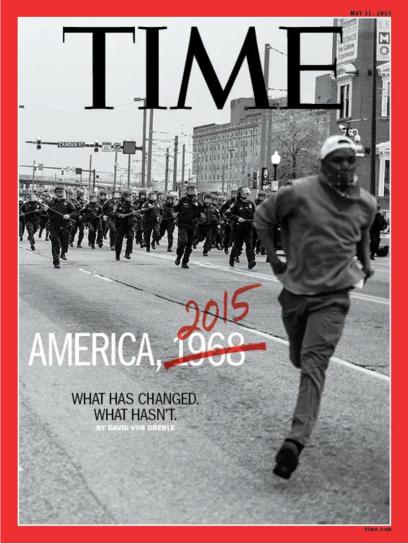

Along with nine other teachers, I became one of the inaugural BMore Me summer fellows. Together, we started with training about the Inquiry Design Model, which focuses on using questioning to better understand and critically analyze historical sources. After training, we were split into teams of two and assigned a grade-level BMore Me unit to work on. My team was responsible for creating a ninth-grade BMore Me unit. We carefully looked at the grade-level Maryland State Standards and Frameworks in Social Studies2 so that we understood what topics needed to be covered for the various units. One of the topics we had to cover in our unit was Reconstruction, which required that students understand what that era in history meant for Black people, as well as the United States as a whole, and Reconstruction’s connection to modern-day racial issues. We decided that we would infuse elements of Baltimore’s history, Maryland’s history, and modern-day topics. Once we had our focused topic, we came up with an essential question: How did we get here, and where are we going? Next, we worked on finding sources and building the ninth-grade curriculum unit from scratch. In the end, we created a unit that taught how the strategic, systemic oppression of Black people during Reconstruction has a direct correlation with and impact on modern-day racial disparities such as mass incarceration and redlining. Most importantly, throughout the unit we included resources showing how Black communities have formed, stood strong, and fought for their rights. For example, to make a connection to our students’ lived experiences, we selected photos of the 2015 Baltimore Uprising (after the death of Freddie Gray in police custody) taken by nationally renowned Baltimore photographer Devin Allen.

While we were creating these lessons, which we had divided up among team members, we got feedback from each other as well as from Ross, the BMore Me lead. After some revisions, the units were completed and approved. Once our written curriculum was finalized, we also had to lead the professional development in the fall for the district’s high school social studies teachers so that they had a firm understanding about BMore Me, as well as how to implement it in their classrooms. After that first year, there was so much excitement from teachers and students across schools (and staff at the district office) about the BMore Me curriculum that Baltimore City Public Schools wanted to expand its reach.

In the midst of the pandemic in 2020, I was able to work with a team of teachers to write parts of a new eighth-grade BMore Me yearlong curriculum from scratch as part of a yearlong fellowship program. After that, other Baltimore teachers created two BMore Me units for grades three through five. And in the summer of 2023, the district wanted to expand BMore Me in grades three through five even further by adding two more BMore Me curriculum units; I was assigned to a team to create one of the two additional fourth-grade units. BMore Me continues to grow, as the district’s end goal is to eventually have full-year BMore Me curricula for grades three through eleven.

BMore Me in the Classroom

Not only did I get to create some of the BMore Me curriculum for my district, I also got a chance to pilot it in my classroom. One of the first things I had to do was get used to students questioning me. Constantly. Questioning is an essential part of using inquiry in social studies, but it can sometimes feel uncomfortable to have students ask questions like, “Why are we learning this?,” “Why does this even matter?,” and “How do you know this stuff even happened?” It definitely feels like students are resisting, but the bigger picture is that those are fair questions to ask. As an adult, if I’m in a professional development session, I’m asking these same questions in my head (and frankly, sometimes out loud) that students like to ask about content. Students, much like us, want to know the purpose of it all. So instead of shutting down those types of questions or taking them as a personal affront, I let students know that their questions are amazing. I ask them, “Why might we have to learn this?” or “Why might this matter?” I reframe their questions and invite them to join the journey of a deeper dive into social studies so that we all can try to find possible answers to their very relevant and key questions. Those types of questions are amazing because students are already using their inquiry-driven minds to try to find answers. It shows their capacity to really get into BMore Me and other related lessons.

Questioning is at the root of good inquiry. Therefore, when starting off my social studies classes, I let my students know I’m there to support them in thinking critically by analyzing and comparing sources and historical events and asking questions to get a broader understanding of a topic. One of the best ways I have found to support students in questioning is the Stanford History Education Group’s Historical Thinking Chart (which is available for free at go.aft.org/d31). It includes questions that spur students’ thinking, such as “What is the author’s perspective?,” “How might the circumstances in which the document was created affect its content?,” and “What claims does the author make?” Using these questions helps students look more closely at sources, consider authors’ intentions, and look across documents for differing perspectives—all of which are crucial for coming up with a strong argument.

Once we dig into the BMore Me curriculum, students quickly learn that the social studies classroom is a place to engage in research, question everything, discover multiple perspectives, and make connections to different topics, the world around them, and themselves. For example, one BMore Me unit from the eighth-grade full-year BMore Me curriculum has students looking at the American Revolution and its impact on Black people. In order to discover and understand the impact of the American Revolution, students have to closely examine and compare many sources, such as a broadside by enslaved Black people in Massachusetts,3 “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation,”4 the Virginia Declaration of Rights,5 and the “Book of Negroes”6 to come up with their arguments regarding how the American Revolution impacted Black people.

Using both primary and secondary sources, students examine the conflicts between the British and the white colonists and the democratic ideals of liberty and individual rights embedded in the Declaration of Independence. They look at the impact of the American Revolution on Baltimore and Maryland. Students also examine sources that show the perspectives of Black and Native people during this period. I’ll never forget that at the end of this BMore Me unit, one of my students commented, “They’re [white colonists] fighting for their freedom from Britain, but they’re preventing Black people from being free. Everybody deserves to be free. Not just certain people.”

With this BMore Me unit, students discover the contributions, bravery, and triumphs of Black people who were part of the American Revolution. They get to see Black people fighting for and being involved in the American Revolution because they were also seeking life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. By reading and analyzing various sources, questioning those sources, and collaborating and discussing with peers, students can see a broader, more complex picture of the American Revolution.

In addition to classroom-based lessons, BMore Me encourages teachers to have students use community resources and experience field trips to more fully grasp the classroom content and make deeper connections to their city and state. I made sure that students got to connect their learning outside of the classroom as much as possible. One trip that sticks out is when I took students to tour the Maryland General Assembly in Annapolis as we were learning about how a new government was set up as a result of the American Revolution. We made connections to our state government and the process of a bill becoming a law. Once in Annapolis, students met their district representatives and asked them spontaneous questions. They saw firsthand how these Maryland government officials work for and represent them. They saw bills being debated. They made connections to what we learned and saw in real time in Maryland’s legislative process. This field trip was such an awesome experience. Just reading a textbook, recalling specific vocabulary, or hearing me drone on and on about how the state government works would not have given the students that desire to learn more—but seeing their government in action sparked questions and spurred them to find answers.

With the BMore Me curriculum and lessons, students strengthen their natural ability to question and use it to think critically and analyze sources to understand other connected topics. For example, our study of Black people and the Revolution led students to wonder about the impact of American chattel slavery on Black people and the United States. They continued the inquiry process by reading local pre–Civil War newspaper ads announcing arrivals of ships with, and auctions of, enslaved people as well as post–Civil War newspaper ads from formerly enslaved people seeking loved ones stolen from them through slavery. Delving into critiques of the institution of slavery, we read excerpts from books by formerly enslaved people: Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,7 Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself,8 and Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself.9 Those excerpts from formerly enslaved people showed how they cherished their literacy—and that it was a form of resistance (since literacy for enslaved people had been outlawed). We also examined a large swath of related primary and secondary sources on the topic, including Maryland slave laws and Maryland newspaper ads announcing slave auctions. This constant inquiry gave students the chance to fully analyze sources, discuss what they found, and ask questions to better understand the impact of slavery on people and our country.

BMore Me inquiry lessons are effective with younger students too. Sometimes, people express their hesitation about teaching inquiry-based social studies to elementary school students. They say that students are too young to understand primary and secondary sources or to formulate independent arguments based on their analyses of sources and collaboration with peers. Unfortunately, this is a misunderstanding of elementary students’ abilities.

In my current position, I get to see firsthand how the BMore Me fourth-grade units help develop students’ historical thinking and document-analysis skills. During a BMore Me unit in the spring of 2023, these amazing fourth-grade students were able to learn about the legacy of Indigenous people. We didn’t tell them what the legacy was. Instead, we let them explore by grappling with primary and secondary sources and discussing with each other as they tried to understand the impact of colonization and the resilience of Native people. I witnessed students

- examining artifacts to see how various Indigenous groups in Maryland lived, communicated, and survived;

- analyzing primary sources such as maps from John Smith and other colonists of the time to see what clues they could gather about Indigenous groups since their perspectives were not in those primary sources;

- reviewing several sources to determine how Indigenous people’s lives were impacted by the arrival of Europeans and the subsequent loss of things like their land; and

- looking at examples of Indigenous people in modern society who maintain the legacies of their ancestors.

As students were learning about the impacts of European exploration, in particular a lesson related to Christopher Columbus, one student took it upon himself to Google Columbus to learn more. Because the student had seen that the social studies classroom was a space for observing and questioning, he was willing to risk asking questions he was mulling over in his mind. While doing his independent research, the student came across some information about people not respecting Columbus or his legacy. Immediately he asked me, “Why don’t they like him?” It was the perfect opportunity for the student to continue using his inquiry skills to find an answer to his question. I said, “I don’t know,” and asked a follow-up question: “Maybe you can go back to the many sources you’ve looked at over the past few days. Based on those, why might they not like Christopher Columbus?” He thought about it and answered, “Maybe because he took people’s land. He also killed people and made them slaves.”

I continued this conversation because it was great seeing the student take this interest and try to make sense of his questions and the various sources he read. “So, what about in Baltimore? Do people in Baltimore have different views of Christopher Columbus?” The student continued his research during class and found a local news station video clip about a Columbus statue being tossed in the Baltimore Harbor by protestors.10 He asked more questions, and I had him go back to the sources we used in class, as well as the sources he found himself. He was able to come up with his own understanding of why some people did not like Columbus, based on his close analysis and questioning of sources. I didn’t shield him from finding answers or simply give him an answer. Why? Because that inquiry was so important for him to make meaning for himself. He was empowered with his learning to know that he can ask questions and that he has the capacity to research and find his own answers.

Historical inquiry and analysis need to be developed over time. Embedding inquiry and document analysis experiences in elementary social studies classes is a good way to start. Not giving elementary students the space to use inquiry in their social studies classes is a missed opportunity for students to thrive in their understanding of historical topics generally covered in elementary grades, such as slavery, the Civil War, and the establishment of the 13 colonies. When students in lower grades experience BMore Me inquiry lessons, they gain key foundational understanding of historical events and related skills needed to excel in their middle school and high school courses, as well as to be generally prepared for life after graduation. Even better, they experience social studies as a fascinating subject open to multiple perspectives and debates—not as a dry series of facts.

The success of the BMore Me curriculum is that it invites students to grapple with and make meaning of these various sources. Because they’re making meaning and trying to make sense of things, they excitedly engage in rich discussions so that they can eventually express their own ideas.

BMore Me Outside of the Classroom

One of the amazing things about the BMore Me curriculum is that it’s not confined to the classroom or a school building. Baltimore City Public Schools holds annual BMore Me events with guest speakers from the Baltimore area, as well as an end of the school year BMore Me Student Conference in which students get to mingle with other kids from around the district and take part in student-led sessions meant to empower them, expose them to new ways of advocating, and help them develop new skills.

For example, in the fall of 2022, there was a BMore Me student event at Coppin State University where students met contributors to Homegrown, a youth-focused book with writings and creations by Baltimore leaders.11 (Published by CHARM: Voices of Baltimore Youth, Homegrown was curated by the 20 middle and high school students who make up CHARM’s editorial board.) While at the event, students heard Brittany Young, founder of B-360, talk about the beauty of being from Baltimore and embracing that unapologetically, as well as how she used her skills and expertise to create her nationally recognized STEM-based program that uses dirt bikes (a part of Baltimore’s culture) to engage kids across the city.

Also, the 2023 BMore Me Student Conference at Morgan State University allowed students to choose sessions that related most to them and their interests. One session that stood out to me was “I Am Because We Are: Where Poetry Meets Identity.” It was a workshop taught by Unique Robinson, a native Baltimore poet and professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art. Students created self-portraits through poetry so that they could continue understanding their own identities. Another session was “Youth Advocacy,” in which students learned what it meant to be an advocate and how to be student advocates in their schools and communities. And a final great session was “A Breakdown of Black Butterfly and White L.” This session focused on helping students understand decadeslong redlining in Baltimore and track the wealth of one Black family and one white family from the 1970s to 2020 to see how redlining has impacted Black and brown communities throughout Baltimore, as well as the city as a whole. The goals of all the sessions were for students to understand and define their own identities, better understand the reasons behind problems in the city, and gather some of the tools needed to become the next generation of leaders. (To learn more, see this Q&A with Kameran Rogers, one of the students who planned and led the 2023 conference.) These BMore Me events give students an amazing opportunity to apply and expand their learning of social studies into their own lives and surrounding communities.

The Value of Inquiry-Based Curriculum Like BMore Me

My students are definitely better thinkers and writers than I ever was at their age. They have these amazing social studies skills because they do inquiry in their social studies classes with the BMore Me curriculum. They are exposed to various topics and multiple perspectives, and they are encouraged to question sources and collaborate with other students through discussions and presentations so that they can come to their own fuller understanding of historical topics. They’re constantly tasked with taking risks in their thinking and questions so that they can make greater connections to history, themselves, and their community.

When thinking about the immense value of inquiry, I am reminded of the bell hooks quote, “Most children are amazing critical thinkers before we silence them.”12 Inquiry-based curriculum like BMore Me allows students to freely be critical thinkers as they try to make sense of the world, the historical past, and their opportunities to impact the present.

Suggestions for Creating Inquiry Lessons in Social Studies

1. Begin with teacher collaboration: While teachers can develop inquiry-based units individually, the work is much more rewarding—and manageable—when done collaboratively. Consider using your school community of teachers to build these lessons. You can partner with your content and grade-level team members to see how to align lessons with what students are learning in other classes.

2. Center students: When creating social studies inquiry lessons that suit your community and region, keep the students in mind. The focus is not teacher-centered instruction, where the teacher stands in front of the class imparting information for students to summarize, memorize, and recall on a test. Instead, the focus is on using students’ natural curiosity and exploration, as well as their identities, to engage them and connect them to the historical topics discussed in class.

3. Provide essential questions: BMore Me inquiry lessons are rooted in a big open-ended question for each unit and one or two specific supporting questions for each lesson. These questions are meant for students to critically think about sources and historical events before coming up with their own arguments. An abundance of questioning leads to deeper student understanding about various topics so that they can make connections to themselves and our larger society.

4. Foster meaningful student-to-student collaboration and discussion: BMore Me inquiry lessons are meant to have students collaborate as a classroom community. Lessons should include space for students to discuss sources together, answer each other’s questions, and make sense of historical topics.

5. Use local primary and secondary sources: One of the things that makes BMore Me special is its focus on local history in Baltimore and in Maryland. As you plan units, it’s important to find and use primary and secondary sources from and about your community and region to enrich students’ understanding of historical topics. For example, your area may have similar resources like the Maryland Center for History and Culture (mdhistory.org), which has an abundance of primary sources related to our region.

Sidney Thomas (she/her) is an educator in Baltimore City Public Schools. She was a BMore Me fellow who developed and wrote equitable social studies units for her own classroom and for BMore Me. She was the 2021 Baltimore City Schools Teacher of the Year and a finalist for Maryland Teacher of the Year.

Endnotes

1. S. Trent, “Teens Embrace AP Class Featuring Black History, a Subject Under Attack,” Washington Post, December 2, 2022, washingtonpost.com/education/2022/12/02/ap-african-american-studies-black-history.

2. Maryland State Department of Education, “State Standards and Frameworks in Social Studies: Standards and Frameworks in All Grades and Disciplines,” marylandpublicschools.org/about/pages/dcaa/social-studies/msss.aspx.

3. P. Bestes et al., letter to the representative of the town of Thompson, Boston, April 20, 1773, loc.gov/resource/rbpe.03701600/?st=text.

4. Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, 1775: A Spotlight on a Primary Source by John Murray, Lord Dunmore,” History Resources, gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/lord-dunmores-proclamation-1775.

5. US National Archives, “America’s Founding Documents: The Virginia Declaration of Rights,” September 29, 2016, archives.gov/founding-docs/virginia-declaration-of-rights.

6. Ncurrie, “Record of the Week: The Book of Negroes,” US National Archives and Say It Loud, February 5, 2015, rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2015/02/05/rotw-the-book-of-negroes.

7. H. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, ed. M. Child (Boston: 1861), pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2924t.html.

8. F. Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), utc.iath.virginia.edu/abolitn/dougnarrhp.html.

9. O. Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself, vol. I (London: 1789), docsouth.unc.edu/neh/equiano1/equiano1.html.

10. D. Politi, “Baltimore Protesters Topple Christopher Columbus Statue, Toss It into Inner Harbor,” Slate, July 5, 2020, slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/07/baltimore-topple-christopher-columbus-statue-inner-harbor.html.

11. CHARM: Voices of Baltimore Youth, Homegrown: A Message to Baltimore by Baltimore (Baltimore: October 6, 2022), charmlitmag.org/products/homegrown-pre-order-hardcover.

12. G. Yancy and b. hooks, “bell hooks: Buddhism, the Beats and Loving Blackness,” New York Times, December 10, 2015, archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/12/10/bell-hooks-buddhism-the-beats-and-loving-blackness.

[Illustrations by Sonia Pulido]