Simeon is a third-grader in Mr. Mitchell’s elementary school classroom. His winning smile and outgoing personality have gained him plenty of friends. But he’s also a master at distracting his peers during independent work. This particular day, he repeatedly reaches into Daniel’s space, taps his fingers, and makes the sound of a drumroll. Mr. Mitchell cajoles him, cautions him, and finally calls him to the side of the room to speak to him privately. The only effect seems to be that Simeon turns his intrusive sounds and motions toward Kayla instead of Daniel. Finally, Mr. Mitchell announces in front of the whole class, “Simeon, you either get to work right now and stay focused, or you will stay in and do your work while the other children are at recess!"

Will the threat of losing recess be enough to motivate Simeon to become productive? How many times will the threat work before Mr. Mitchell has to carry it out and show Simeon and his classmates he is serious? Once he does, will Simeon become more studious—or will he become one of those children who frequently lose out on recess?

The question Mr. Mitchell must ultimately answer is this: Is recess a reward to be earned only by the children who are on task and who comply with academic and behavioral expectations? Or is recess an important part of every child’s school day, offering benefits—to physical health, social development, and sense of autonomy—that are too important to be taken away?

We know that Mr. Mitchell is not alone in his predicament. In a 2010 Gallup survey, 77 percent of principals or other building administrators said that some or all of their teachers used withholding of recess as punishment.1 Based on our qualitative studies of classroom teachers in elementary schools in Illinois, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Texas, we have witnessed the uncertainty of teachers who use this strategy. Even among educators who do withhold recess, many worry that the strategy is at best a weak and imprecise disciplinary tool that could backfire. At a loss for other ways to improve student motivation and behavior, many teachers seem to have arrived at the same conclusion as Tamar, a thoughtful third-grader we interviewed: “I’ll say it is a good consequence, since a lot of kids like recess.”

The purpose of this article is to promote a deeper, more complex understanding of the challenge that “recess time” poses to elementary school educators and to thereby understand the practices in which they are currently engaging. Because teachers are expected to shepherd students through a vast array of learning standards while remaining sensitive to their social, physical, and emotional well-being, decisions about who gets to participate in recess are made under great pressure. Also, teachers often correctly perceive that only limited resources are available to help them.

After sharing what we have learned about teachers’ perspectives, we will briefly discuss two examples of school initiatives that support teachers in managing classrooms while ensuring that recess remains part of every child’s day. It is our hope that by reading this article, educational leaders working on this issue will see the necessity of engaging classroom teachers in the big-picture discussions about recess and related health and wellness policies.

The Benefits of Recess and Why Teachers Sometimes Withhold It

With the support of selected elementary school principals, we distributed a survey in three school districts in Massachusetts (March 2014) and two in Ohio (February 2017). We interviewed a small sample of teachers in those two states as well as a sample of teachers in Illinois and Texas. The survey included questions asking for quantitative responses (e.g., “How many children have you held out of recess at least once during the current academic year?”) and others calling for qualitative responses (e.g., “Check off from the following menu all the reasons you held children from recess”). Respondents also had a number of opportunities to expand on their answers with open-ended comments.

The data we present here show teachers’ attitudes toward recess and their practices relating to withholding it as a disciplinary tool. While these results can add an important dimension to the dialogue about recess, they should be taken as suggestive, not definitive. Participation of teachers in such a survey could only take place in schools where superintendents and principals chose to cooperate with our inquiry; we do not make claims about the randomness or representative nature of our sample.

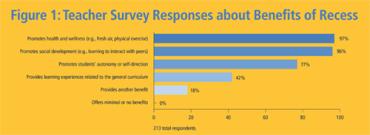

When asked about the ways recess benefits their students, 100 percent of respondents said recess was beneficial and selected at least one benefit from providing recess; not one checked the box indicating their belief that recess offers “minimal or no benefits.” The two types of benefits most teachers agreed with overwhelmingly were, “Promotes health and wellness (e.g., fresh air, physical exercise)” and “Promotes social development (e.g., learning to interact with peers).” More than 96 percent of teachers checked off each of these options, as shown in Figure 1. A majority of respondents (77 percent) also felt that recess “Promotes students’ autonomy or self-direction,” while 42 percent checked off the box that recess “Provides learning experiences related to the general curriculum.” Eighteen percent wrote in an additional benefit, such as promoting self-confidence, creativity, and problem-solving abilities, besides the menu of four choices we offered.

(click image to enlarge)

One second-grade teacher we interviewed, in expanding on her ideas about the benefits of recess, also provided a critique of her district’s reasons for having reduced recess:

Our school district has limited young children to one 25-minute recess per day in an attempt to pretend that more learning is taking place. Our second-graders are forced to endure a three-and-a-half-hour morning with no break. This, in my opinion, is counter to better learning. A short outdoor break would bring the students back refreshed, and then more actual learning would take place. Even adult retail workers get more breaks than our 7- and 8-year-olds.

Despite the unanimous response that recess offers important benefits to students, two-thirds (68 percent) of our respondents had withheld all or part of a recess period from at least one student during that school year—individually, and not as part of a classwide loss of recess. (Classwide loss of recess was something we did not explore in our work, as we wanted to learn about the withholding of recess from individual students as a disciplinary strategy.)

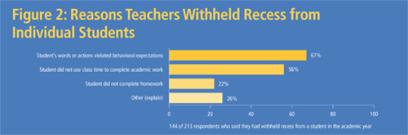

The biggest proportion of these teachers (two-thirds of the two-thirds who used this form of discipline) had withheld recess because a “Student’s words or actions violated behavioral expectations.” As shown in Figure 2, smaller proportions had denied recess for other reasons: 56 percent for not getting work done during class, and 22 percent for failing to complete and turn in homework. Twenty-six percent of respondents volunteered another reason for withholding recess, such as students engaging in unsafe behavior at recess, not following recess rules, not completing class work, and needing academic intervention.

(click image to enlarge)

When asked whether teachers think taking away recess is “working” to accomplish the intended outcome (i.e., improved behavior or improved academic attention/work completion), the answers were mixed. Teachers pointed to examples of students they felt had corrected their behavior or improved their classroom productivity after experiencing the loss of recess—or even just a portion of recess—as little as one time. However, most teachers seemed to feel that in denying a student recess as often as four times a month, the sanction was probably not having the desired effect.

The Need to Include Teachers

Substantial numbers of elementary school teachers are withholding from recess the very children they tell us “need it the most.” Nearly all of these teachers wish they had other ways to motivate their students, as they clearly do not question the intrinsic value of recess time. Teachers expressed a need for support in developing alternatives to withholding recess. That begins with engaging teachers in a school’s development of consistent academic/behavioral expectations, consequences, and strategies.

Connecting recess with these whole-school initiatives requires teachers to be included in preparation and adoption. As those closest to students and parents, teachers must be part of the process of embracing common practices and explicit language to ensure recess will not be withheld for academic or punitive reasons. As a result, teachers will not feel “on their own” or “at a loss,” because the culture of the school supports them.

Schools would be well advised to consider the American Academy of Pediatrics’ policy on recess, which states that “cognitive processing and academic performance depend on regular breaks from concentrated classroom work, [which] applies equally to adolescents and to younger children. To be effective, the frequency and duration of breaks should be sufficient to allow the student to mentally decompress.”2 Thus, while each school must examine resources and schedules within the context of its environment, it is possible to build in more than one recess, combined with lunch, to provide frequent, regular breaks.

The benefits of outside play are such that recess ought to be held outside.3 Since this is their personal time, children ought to be able to choose their recess activity—which may or may not involve moderate to vigorous physical activity. Certainly, recess is an opportunity to promote activity and a healthy lifestyle for children, but it is “particularly unstructured recess [that] provides the creative, social, and emotional benefits of play.”4 Extending the concept that regular breaks augment cognitive processing, and that teaching is a cognitive endeavor, when teachers supervise/monitor recess (without directing activities), teachers also take a break from classroom instruction, even if they are on duty as monitors. We suggest that recess not be used as a way for teachers to engage in much-needed planning time. For planning time to be truly productive, it ought not to be squeezed into breaks, such as 15-minute increments for recess.

Examples of teacher-involved, schoolwide initiatives that support educators in managing classrooms without withholding recess are found in the Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) program and the Let’s Inspire Innovation ’N Kids (LiiNK) Project.* In PBIS, the school leadership team, which includes teachers, examines data about discipline, culture, and practices, and decides where change is needed. The team chooses behavioral expectations, frames them with positive language, and creates strategies to support children’s development of these behaviors.

In LiiNK schools, there is also a schoolwide adoption of consistent, positive language to communicate behavioral expectations. LiiNK embeds recess four times a day, coupled with a character education curriculum. The character education component teaches and reinforces the noncognitive skills—such as empathy, respect, and self-control—that are critical to the behavioral expectations for a nurturing learning environment.

The value of recess as part of successful schooling is such that it ought to be considered part of every child’s learning and development. When done well, recess offers children a chance to interact with peers to practice and develop healthy, lifelong social-emotional skills, such as communicating, negotiating, and sharing.

While recess offers children a break from the structured and teacher-directed portions of the school day, it can also be a useful observation time for teachers. The social dynamics and choices students make moving about autonomously may lead to insights about how to work with certain children. They may even find that fresh air and loud, squealing voices is invigorating. Both teachers and students return to the classroom refreshed and ready for learning.

Just as teachers should be invited to contribute to curriculum, textbook, and scheduling decisions, it is imperative that they also be included in initiatives and decisions related to recess. At the school district level, recess is most often one component of the district’s wellness policy. Many such policies offer general guidelines but do not translate directly into the classroom; a general statement supporting the right of recess for every child does not offer Mr. Mitchell any concrete support for dealing with Simeon.

Engaging more teachers in crafting those policies will tend to make them more specific and applicable at the classroom level. The more we involve teachers, the more we are likely to identify specific steps that will turn a vision of a healthier school climate into a recipe that works in the classroom, thus ensuring that every child’s recess is protected regardless of classroom behavior, and that teachers have supportive leaders, peers, and strategies to carry out such an important policy.

Catherine L. Ramstetter is the founder of Successful Healthy Children, a nonprofit organization focused on school health and wellness. Dale Borman Fink is a professor of education at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.

*For more on promising programs that support recess, see “Time to Play” in the Spring 2017 issue of American Educator. (back to article)

Endnotes

1. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “The State of Play: Gallup Survey of Principals on School Recess” (February 2010).

2. American Academy of Pediatrics, “Policy Statement: The Crucial Role of Recess in School,” Pediatrics 131, no. 1 (2013): 186.

3. Deborah J. Rhea, Alexander P. Rivchun, and Jacqueline Pennings, “The Liink Project: Implementation of a Recess and Character Development Pilot Study with Grades K & 1 Children,” Texas Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance Journal 84, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 14–17, 35; and Michael Yogman et al., “The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development in Young Children,” Pediatrics 142, no. 3 (2018): 3.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics, “Policy Statement,” 186.