It is a little past noon, and Mission High School's annual drag show is about to begin. The air in the school auditorium is hot, alive with loud chatter and intermittent laughter from a crowd of more than 1,000 students and adults. Scattered blue, pink, and yellow lights move across the sea of teenage faces. The stage sparkles with holiday lights and glitter. The projection screen on the stage reads: "'That's so gay' is NOT okay. Celebrate gay, hooray!" A few students sitting in the front rows are reading posters near the stage. Each displays someone's "coming out testimonial": "I am coming out as Gay, because I am fabulous." "I am coming out as a poet, because everyone should express themselves honestly and creatively!" "I am coming out as straight because I love girls!"

Pablo, a senior, is standing behind a heavy yellow velvet curtain at the back of the stage. His slender shoulders are moving up and down, as he is breathing rapidly. He can hear the voices and laughter on the other side of the curtain. The emcee on stage announces Pablo's name, and the volume of student voices in the audience goes up. His heart is racing. He wipes the sweat off his forehead with a white towel, but the drops reappear. His tongue feels swollen and dry. Pablo asks his friends for a glass of water.

This year's drag show—put on by Mission High's Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA)—has already been going better than all others Pablo has been a part of since he arrived at Mission. The drag show is a homegrown expression created by students of the school, which is located in San Francisco near the Castro district, the historic neighborhood with one of the largest gay populations in the country. The annual show features student- and teacher-choreographed dances, student and teacher "coming out" speeches, short educational videos on LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning) issues, and the popular "fashion show," in which teachers, administrators, security guards, and students appear dressed in drag.

Principal Eric Guthertz steps onto the stage in a white dress with a brown print on it, a blond wig, and red patent leather platforms to introduce the student dance Pablo has choreographed to Nicki Minaj's song "Super Bass." As Pablo and his five friends playfully twist and turn across the stage—dressed in shorts, fishnet stockings, and white tank tops—the audience cheers. Midway through the dance, during a blaring bass solo, a few students get up and dance on their chairs.

Pablo has spent more than a year thinking about the dance moves and his interpretation of the song. He has mixed in traditional dance moves from his native Guatemala: salsa, cumbia, merengue, and tango. Other ideas came from musical artists he admires, like Boy George and Lady Gaga. But the story is all his: he wants to convey the idea that dance, like life, is most meaningful when people are allowed to be whoever they want to be. For Pablo, it means breaking through the rigid confines of gender-based dance moves, allowing students to make up their own.

The emcee announces Pablo's name again. The screaming crowd gets louder. Pablo is scheduled to be the third student speaker in the drag show and will share his coming out story.

"Pablo, please come out," the emcee comes behind the curtain and tells him.

"I need five more minutes," Pablo replies.

What if they throw things at me while I'm talking? Pablo is thinking to himself. He starts shaking.

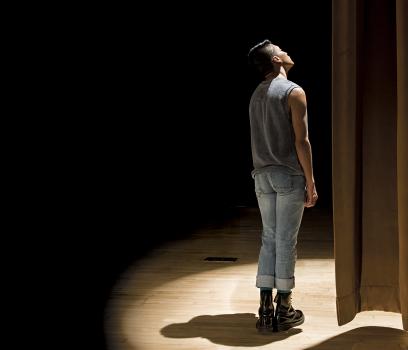

One, two, three, four, five. Pablo is now counting steps in his head, looking at his black Doc Martens, as he moves toward the stage. On six, he raises his eyes toward the lights, standing in front of the podium.

"Hello, Mission High School," Pablo's soft voice interrupts the cheering, and the noise stills.

"My name is Pablo," he says in a warm, confident voice. Then he glances at his written speech on his phone one more time before he continues.

"I describe myself in a million different ways. But today, I will tell you that I am Latino and gay. Just in case you still have struggles with race, gender, and sexuality, let me tell you something. Maybe what you see, maybe the outside, it's different, but on the inside, we are all the same.

"I knew I was gay before coming out. In my sophomore year, I came out to my best friend, Claudia, in a PE class. That morning, I felt brave, I felt free, I felt honest. Sounds easy, but I used to spend a lot of time crying, hating myself, praying to God to 'change' me.

"I got rejected at home. Sometimes, it hurts. But I understand. A lot of things can't go the way you want them to, but you have to learn how to work them out.

"I want to tell you that I am a crazy dreamer, but I am not alone. From Seneca Falls, where the first well-known women's rights convention in the U.S. happened, through Selma, where Dr. King and other organizers led one of the protests for civil rights, to the Stonewall Rebellion, the birth of the LGBTQ movement, and now here in our school, it's called progress, people, whether you like it or not."

Challenges at School

Even though Mission High School sponsors an annual drag show, LGBTQ students still face challenges. At Mission, no one pushed Pablo around or punched him in the stomach. But some days the verbal banter and social isolation were overwhelming. Pablo didn't care as much about the words he heard in the hallways. He tried to walk down the halls with a friend, and the many hallways and staircases made it easy enough to escape tense situations. In some classrooms, though, there was no escape.

In his freshman algebra class, Pablo's teacher asked him to sit in a group of four students. Pablo sat down next to Carlos, a recent immigrant from Honduras, who wore a San Francisco Giants hat and a small cross around his neck, over his T-shirt. Pablo liked math and was good at it. Carlos was a top student in math too, and he was extremely competitive. In the first week of class, whenever Pablo solved a problem before everyone else in the group, Carlos whispered comments in Spanish. "No, you don't know this. You are dumb, because you are gay." The teacher didn't hear the comments.

A few weeks later, when Pablo was graphing a slope on the whiteboard in front of the class, Carlos started calling him names in Spanish out loud. The math teacher heard him this time and sent Carlos to the dean's office. But when Carlos came back, he was even more emboldened and crueler than before, and the situation was no better for Pablo.

On another occasion, Pablo's math teacher was writing out numbers on the whiteboard, and each number was painted in a different color, forming a rainbow. Carlos said in Spanish that it looked like a gay flag. Another student chimed in; she said she didn't think gay marriage was right. At the time, Pablo hadn't come out yet—even to himself. As students joined in, he said he didn't think gay marriage was right either.

"Are you serious?" Carlos turned to him. "How can you turn against your own people?"

Later that day at home, Pablo was suffocating under the unbearable weight of shame. Why am I afraid to come out? Why am I lying? he thought. It was during this quiet, private monologue, sitting in his room alone, that Pablo came out of the closet to himself for the first time.

During his freshman year at Mission, Pablo was in classes for English learners. His English teacher, Deborah Fedorchuk, had all of her students write in journals at the beginning of each class. She would write a topic on the whiteboard, set the clock for 10 minutes, and encourage students to write without stopping. Whatever they wanted to say was fine, she assured them.

One day, she wrote down "Women's Rights," and Pablo surprised himself; he wrote and wrote, and the words kept pouring out. At the end of the paper, he decided that he was "for women's rights" and that he was a "feminist ally." Ms. Fedorchuk loved the essay and discussed it with Pablo at lunch. She enjoyed talking to her students about their journals. Almost every day, Pablo would come to her classroom and discuss with her various political and social issues: green economies and recycling, guns and "cholos" (a Spanish term that most often describes the Latino low-rider subculture and manner of dress), stereotypes, women.

"Ms. Fedorchuk was the first person at Mission who made me feel at home," Pablo recalls four years later, as a senior. "I felt mute until I met her. Her interest in my ideas made me feel alive again. I wanted to be heard so bad. I was so shy and didn't speak English. She made me talk."

Later in his freshman year, Ms. Fedorchuk told Pablo about Taica Hsu (see his article, "How I Support LGBTQ+ Students at My School"), who sponsored the school's Gay-Straight Alliance club, in which students who shared Pablo's views on women's rights debated various social and political issues. Mr. Hsu spoke fluent Spanish and taught math—Pablo's favorite subject. Even though Mr. Hsu wasn't his math teacher, Pablo felt most comfortable asking him for help with math and checking in about anything else that was going on in his life at the time. Pablo started going to the GSA's weekly meetings. He still struggled with his English and was painfully shy at first. But he liked the GSA's president, Michelle—a bold, openly bisexual young woman—who had ambitious ideas for events and campaigns. Eventually, Pablo decided to become the vice president of the GSA.

Once a week, Mr. Hsu, Michelle, and Pablo met to plan the upcoming GSA meeting. During these sessions, Mr. Hsu taught Pablo and Michelle how to write agendas, keep everyone engaged, and make people feel welcome and included during meetings. That year, they organized the first panel at which GSA students educated teachers on ways to intervene when homophobic, sexist, or racist language is used in the classrooms. The idea came about after the group realized that most bullying was happening in the classrooms, rather than in the hallways.

The GSA invited all faculty members to come to the panel, at which students shared real examples of how teachers had intervened in a way they thought was constructive. Pablo was one of the speakers on the panel, remembering how one teacher had responded to an African American student who made the comment "Don't be a fag" to his friend during her class. "Excuse me," the teacher had said, stopping the class with a visible sense of urgency and concern. "We never use that kind of language here. How would you feel if someone said, 'That's so black?' "

Pablo recalled that the student had apologized, and that kind of language didn't occur in her class again. He and other panelists advised teachers to do more of that—to relate LGBTQ bullying to other forms of abuse students at the school can identify with, such as racism or hateful language targeting undocumented immigrants. Mr. Hsu says that almost all the teachers came to the panel and later expressed their support for such discussions with students. Most teaching programs and professional development days in schools don't provide that kind of training on appropriate ways to intervene. Some teachers feel they should say something, but they don't know how to respond appropriately.

As students shared their experiences, they came to the conclusion that some teachers were better than others at stopping abusive language or establishing a classroom culture that proactively prevents bullying in the first place. They decided to share these best practices with all teachers.

The GSA panelists made many suggestions on how to address these issues, including incorporating more LGBTQ content into the curriculum. "A small group of history teachers always included studies of the LGBTQ movements in their history classes, but many don't," Pablo says. "When they do, they show how these movements helped everyone and present gay people in a positive way."

One day during his sophomore year, Pablo's friend Claudia was telling him about her crushes during their physical education class. When she was done talking, she asked, "Do you have someone you like?"

"No," Pablo said.

A week later, she asked Pablo again, while they were doing pushups.

"You know how you tell me that you need to hug a pillow after you wake up from a nightmare?" Pablo said. "Let's pretend I'm having a nightmare right now. I need you to be there for me. There is someone I feel attracted to, and his name is Stephen."

Claudia stopped doing pushups.

"Yes, I'm gay," Pablo said, continuing to do pushups.

"Oh my God!" Claudia said with a smile. "I knew it."

Someone overheard them talking, and the news spread quickly throughout the school.

"It didn't matter anymore," Pablo recalls. "After I came out, I felt like I had space in the school. I felt bigger. I felt like, 'yes, I'm going to cope. I'm going to have good grades.' "

When Pablo came out to Claudia and joined the GSA, he felt physically and emotionally stronger and more confident in his abilities to cope with his new place in the world. At school, Pablo felt that people noticed him more. His grades improved, eventually landing him on the honor roll.

But at the end of his sophomore year, when school was out for the summer, life at home felt more stifling than usual. Pablo was spending more time at his house, where he lived with his mother and two uncles. His inability to be truthful with his mom weighed more heavily on his mind with each passing day.

After living at home grew unbearable, Pablo eventually moved into a friend's house. At school, Mr. Hsu checked on Pablo every day. His attendance and grades plummeted, and Mr. Hsu was worried. He talked to Pablo's teachers and sent out an e-mail asking them to be more lenient with Pablo's deadlines that month. In addition, Mr. Hsu introduced Pablo to his friend Erik Martinez, who was a case manager at a local LGBTQ youth community center and educational organization called LYRIC. Pablo started going to LYRIC every two weeks. He enjoyed talking to Martinez. Pablo didn't want to sit in a small room talking to a therapist about all of the things that were horrible in his life. He wanted to be in a group of like-minded people who were dealing with similar issues. LYRIC provided that community and felt like home. Pablo's relationship with his family remained strained, but he started feeling stronger about his ability to cope with it.

"The [drag show] dance, my expression, the LYRIC family, [that] was my therapy back then," Pablo reflects now. "What I really needed was resilience and building my confidence and skills to speak out."

A Supportive Gay-Straight Alliance

In schools all over the United States, teens who identify as LGBTQ are bullied far more than others.1 A 2013 national survey conducted by GLSEN (the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network) found that homophobic (and sexist) remarks are more common today than racist comments. In addition, 85 percent of kids who identified as LGBTQ said they had been verbally harassed at school, 39 percent said they had been physically harassed, and 19 percent said they had been physically assaulted. These youths are more likely to skip school and have lower grades.2

Studies show that a GSA is one of the strongest buffers a school can build to reduce the bullying of gay teens. In schools with GSAs—according to journalist Emily Bazelon, author of Sticks and Stones—kids experience less abuse, have higher grades, and feel a greater sense of belonging.3 There are about 3,500 GSAs in the United States, mostly in high schools but some in middle schools, according to the national Genders & Sexualities Alliance Network (GSA Network, formerly called the Gay-Straight Alliance Network). Founded in 1998, the GSA Network supports GSAs, and helps students establish them, in schools across the country.

The GSA Network, which unites statewide GSA organizations and promotes the GSA movement nationally, considers Mission one of its strongest and most effective local chapters in the country. Mission students, teachers, and administrators say that their GSA draws most of its strength from an authentic student ownership model. The work of its leadership is then reinforced by a larger, school-based approach designed to reduce stereotypes and biases, including sexism, racism, and the bullying of students with disabilities.

Most local GSAs look for guidance from the GSA Network, which coordinates large events for local chapters to participate in, such as National Coming Out Day. This national campaign raises awareness of the LGBTQ community, highlights commonalities among gay students and others who live with complex or multiple gender identities or who struggle with exclusion, and gives LGBTQ students in each school the ability to express themselves publicly.

Distributing forms for National Coming Out Day was one of the first campaigns Pablo ran when he joined the GSA, encouraging students to reveal hidden or lesser-known sides of their identities. As forms dotted the walls of Mission, some students came out as queer, others as allies of LGBTQ friends and family, and others as poets, punk rockers, dancers, food lovers, and secret admirers. Pablo says that in his freshman year, about 20 students filled out the forms. By his senior year, more than 300 did.

During his sophomore year, Pablo danced in his first drag show. It was the first time Mission opened up the event to the entire school, after four years of gradual buildup. As he danced, the vast majority of students clapped and cheered. A few yelled out crude jokes, and teachers had to walk several students out. When one student was reading her "coming out" testimonial, someone threw a piece of crumpled paper at her. The ball didn't make it to the podium and landed in the front rows.

Even though the reception of the first public show was not as welcoming and widespread as the one at which Pablo read his testimonial two years later, he felt a tangible change at school the next day. As he walked down the hallways, countless students approached him to express support. He also noticed that students who didn't fit in—socially isolated and bullied kids who were not LGBTQ—wanted to talk to him. Some said they wanted to dance in next year's drag show. Others wanted to share their own stories of social exclusion, racism, or bullying.

"Before the drag show, I was a freak and it was a bad thing," Pablo recalls. "Now, it became a good thing. Many students still looked at us as weird, but now we were also cool. We know how to dance, how to put on the most popular party at school, and we are good at listening to different people."

When Pablo became the vice president of Mission's GSA in his sophomore year, he proposed that the GSA put even more energy into homegrown activities designed by students. He also wanted to put on more events that celebrated queer culture; he felt that too many events focused on the ways in which LGBTQ teens were being repressed. "I didn't want Mission High to see gay students only as victims or negative statistics," he says. "I wanted everyone to see us as the most active and positive people at the school." If the GSA could put on the most popular parties at the school, Pablo reasoned, the club would attract many more allies, who would then become powerful ambassadors and disseminators of a culture of respect among students who would not otherwise connect to the GSA on their own. These student allies would also be taught to intervene and stop the spread of homophobic language.

Kim, a straight member of the GSA, is a perfect example of how Pablo's strategy worked. "I loved the dances, and that's why I joined, and so many others do too," she explains. "What appealed to me is that the drag show was the only place at the school where the dances were modern, not traditional. I love Lady Gaga, and I wanted to dance to pop music. As we were practicing for the drag show, I learned about the meaning behind these dances and the drag. But we also just hung out a lot and talked about life, and I learned about how hard it was for LGBTQ students to be out. I learned about the high number of suicides among gay teenagers.

"The drag show was the most powerful recruitment tool. My friends saw me dance and wanted to join, and I'd say, 'Oh, I'm going to a GSA meeting today,' and they'd just come and hang out. At any time, half of the kids were just hanging out there, eating pizza and seeing straight people they know support LGBTQ people."

Pablo's third and final drag show was the most popular event at Mission among students that year, and because it was open to the entire school, it was probably the only event of its kind anywhere in the country. When Pablo read his testimonial to the audience, the auditorium—filled with more than 900 teenagers from dozens of cultural and religious backgrounds—was so quiet and respectful that Pablo's breathing could be heard in the microphone. Some of the loudest cheers of support came from Carlos, Pablo's biggest tormentor four years earlier. A month after the drag show, Pablo helped Carlos find his first job out of high school.

While the situation for LGBTQ youth remains dire in too many schools across the country, the school climate for all students at Mission visibly improved from 2010 to 2014, according to students. In a districtwide 2013 student survey, 51 percent of Mission 11th-graders reported that other students "never" or "rarely" made harassing statements based on sexual orientation, compared with 28 percent from the same grade in other schools. Significantly higher percentages of Mission 11th-graders also reported that "this school encourages students to understand how others think and feel" and that "students here try to stop bullying when they see it happen."4

Educators at Mission agree that the success of any antibullying initiative depends on the degree of student ownership of the strategies for solutions. A GSA club, a drag show, or any other antibullying strategy that is superimposed by adults without genuine leadership and engagement by the students will not work. Another thing that wouldn't work, Pablo adds, is expecting that one club, like a GSA, can by itself change the entire school culture.

Mission supports dozens of clubs that celebrate diversity, individual difference, and inclusive leadership. But most of the important work happens in the classroom, Pablo says. Teachers who are in charge of their classrooms know how to set up classrooms that encourage positive social norms and effective group work and collaboration among students. They model behavior. They show students how to stand up for others and stop abuse effectively. And most important for Pablo, great teachers find relevant, intellectually challenging content that not only teaches history, fiction, grammatical conventions, and vocabulary, but also pushes students to explore the meaning of courage, empathy, honesty, forgiveness, and taking responsibility for one's own actions.

Kristina Rizga is a senior reporter at Mother Jones, where she writes about education. This article is excerpted from Mission High: One School, How Experts Tried to Fail It, and the Students and Teachers Who Made It Triumph by Kristina Rizga. Copyright © 2015. Available from Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group Inc.

Endnotes

1. Diane Felmlee and Robert Faris, "Toxic Ties: Networks of Friendship, Dating, and Cyber Victimization," Social Psychology Quarterly 79 (2016): 243–262.

2. Joseph G. Kosciw, Emily A. Greytak, Neal A. Palmer, and Madelyn J. Boesen, The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth in Our Nation's Schools (New York: GLSEN, 2014).

3. Emily Bazelon, Sticks and Stones: Defeating the Culture of Bullying and Rediscovering the Power of Character and Empathy (New York: Random House, 2013), 77.

4. California Department of Education, California Healthy Kids Survey: San Francisco Unified Secondary 2013–2014 Main Report (San Francisco: WestEd, 2014); and California Department of Education, California Healthy Kids Survey: Mission High Secondary 2013–2014 Main Report (San Francisco: WestEd, 2014).