When it comes to in-person learning, the AFT has a very clear message: our students need to be in their schools and on their campuses. The COVID-19 pandemic has created far-reaching challenges for educators and learning institutions, but with adequate safety measures, schools can be open. And they should be. The positive effects of in-school learning are well documented.1

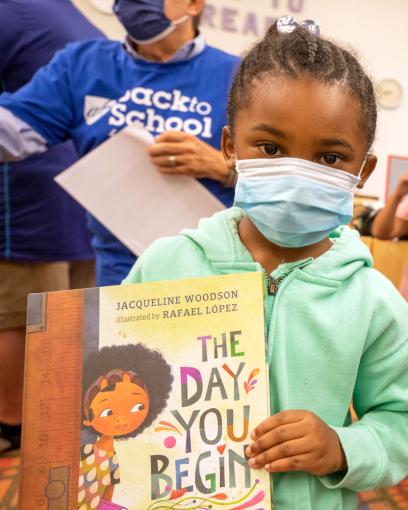

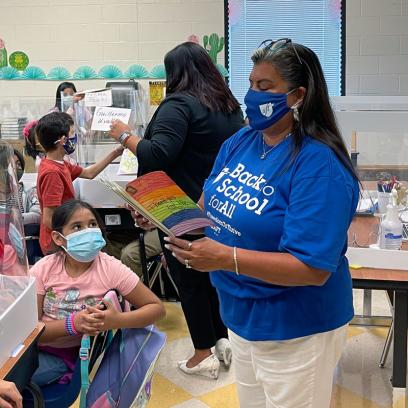

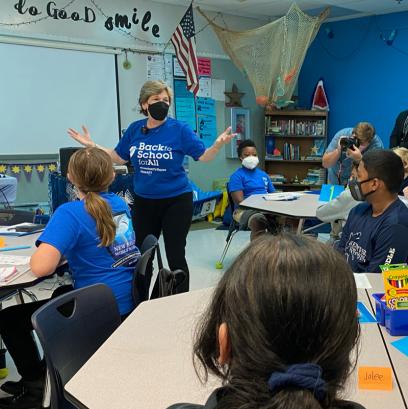

Starting from that premise, the AFT launched a national Back to School for All (B2S) campaign in the summer of 2021. According to AFT President Randi Weingarten, the B2S campaign was a concerted effort by teachers and staff across the United States to tackle barriers to safe, in-person learning and to ensure that all students feel welcome. “Our members have talked to thousands of parents, done hundreds of walk-throughs of school buildings, stood up vaccine clinics, given away books, and yes, had some fun doing it,” Weingarten noted.2 The campaign served as a catalyst for bringing students back into public schools, colleges, and universities through a vast public outreach effort. The AFT awarded a total of $5 million to over 75 grantees covering more than 1,800 AFT affiliates serving some 20 million students.3 Importantly, the campaigns also countered misinformation about public health efforts, demonstrated the important role unions play in education and society, and helped build stronger relationships between local affiliates and the communities they serve.

Now that teachers, school staff, and AFT affiliates are preparing for the coming school year, we thought it would be a good time to review campaign efforts from last summer. What are some of the major lessons learned? What strategies and tactics were used? How effective were they? And how can teachers build on those efforts this coming school year and beyond?

To answer these questions and more, we surveyed* B2S grant recipients from both preK–12 and higher education affiliates and conducted focus group interviews with teachers, union leaders, and community partners from three case sites: Martinsville, Indiana; two communities in New York; and several communities in Texas. (For our case studies, see here.) We hope that readers draw inspiration from the work and stories of fellow educators who have been strengthening their unions’ connections with students, families, and communities and working to ensure all students feel safe and welcome in their classrooms.

This work is all the more urgent because the United States saw an unprecedented decline in student enrollment in public schools, colleges, and universities over the past two years. The National Center for Education Statistics reported approximately 1.5 million fewer K–12 students attending public schools in 2020–21 compared with the previous school year—a decline of roughly 3 percent.4

Various disruptions triggered by COVID-19 and remote learning were identified as major factors driving many families to leave public schools. But COVID-19 is only part of the story. As we heard from many survey respondents and interviewees, enrollment had been declining or at best stagnating in the years leading up to the pandemic. Many cited the rise of school choice and voucher systems accompanied by aggressive recruitment efforts by private and charter schools. Shifting industries, job losses, and a lack of affordable housing and childcare were also cited as preexisting reasons for enrollment decline in some localities.

The decline has been somewhat worse in higher education. Total undergraduate enrollment at public four-year institutions was 4.5 percent lower in fall 2021 than in fall 2019.5 Our survey respondents identified students needing to work, pandemic-related family illness or death, and anxiety about safety as among the major factors leading some students to not return. Some respondents fear that many of the students lost momentum and may not return to college unless someone reaches out, encourages them to return, and helps them to do so.

Crafting a Solution: Back to School for All Campaigns

Against the national backdrop of declining enrollment, constrained budgets, and political division, the AFT launched its national Back to School for All campaign. The overarching goal of the effort, as stated in the call for grant proposals, was to “create welcoming and safe environments where all students thrive.” From our survey, we identified a number of complementary goals set by state and local campaigns: safely returning to in-person schooling, increasing school enrollments, increasing vaccination rates, improving social and emotional well-being for students and teachers, building more collaborative relationships with school administrations, and strengthening ties between unions and their communities.

The campaigns used a variety of strategies and tactics to achieve their goals, including media promotions, worksite visits, tabling at local events, community canvassing, hosting vaccine clinics with community health partners, and more. About three-quarters of respondents reported using a combination of social, earned, and paid media to get the word out about important campaign events and to reinforce messaging from phone banking and canvassing efforts. Just over half of respondents indicated they engaged in some form of internal member organizing to carry out campaign activities. About half reported tabling at public events, and a similar number reported phone banking and text messaging. Importantly, many highlighted the value of being able to support families in need, indicating that hosting public events that provided necessary services to their communities bolstered not only event attendance but also overall respect for and greater understanding of the role that unions play in school communities.

When asked to rank their strategies and tactics, most campaigns surveyed found community canvassing to be the most effective. Some of the positive benefits included being able to have deeper conversations with community members about their specific needs, providing parents and caregivers an opportunity to clarify vital information impacting their decisions to return to in-person learning, and gaining insights beyond pandemic-related concerns on what the community needs for its overall well-being.

The survey data revealed some variation in tactics used by schools with differing demographic characteristics. Majority-Black or majority-Latinx/Hispanic school districts were more likely to engage in community outreach, while majority-white school districts were more likely to engage in internal member organizing. We also found vaccine clinics were more common among locals in school districts that primarily serve students of color. For example, 33 percent of respondents from majority-African American schools reported hosting vaccine clinics, whereas just 11 percent from majority-white schools did so. This makes sense given the initial hesitancy about vaccines among many African Americans6 as well as the structural barriers that often made it harder to access free vaccines in many under-resourced neighborhoods.7

Grantees also used printed materials (flyers, cards, surveys), technology (phones, texting, social media), union staff time, advertising (radio, TV, billboards, print, internet), and political capital (voices of elected leaders and community leaders). Some locals distributed resources such as backpacks, books, hand sanitizers, and KN95 masks. Others worked with social service organizations to connect community members with food pantries and rental assistance. Notably, over three-quarters of campaigns surveyed indicated that volunteers were used in their campaign. Some campaigns compensated members for participating, although most members volunteered their time.

Some of the major challenges reported by preK–12 locals in the survey included a polarized political climate, school budget constraints, teacher shortages, vaccine hesitancy, and negative perceptions of teacher unions in some areas. Respondents from higher education locals overwhelmingly said that budget cuts were a major challenge during the pandemic. Other issues included increased difficulties with students being able to finance their education as well as member work overload. Recent reports have documented that the transition to online learning greatly exacerbated the workloads of many educators, at both the higher education and K–12 levels.8

Across most of the preK–12 locals surveyed, respondents noted that public support for union-led vaccine clinics was high in most instances, but securing participation required education and conversations in areas where community members were more hesitant. Only a few locals reported facing anti-mask and anti-vaccine protestors.

Beyond pandemic issues, some locals were grappling with negative public perceptions of the union—or unions in general—particularly in more politically conservative regions. “The biggest challenge,” one survey response said, “was to engage the community in a short amount of time and establish relationships with school district stakeholders. Many people fail to understand what unions actually do. It’s not just about protecting teachers—it’s also about engaging communities. And due to [our political climate], many people think that unions are socialist organizations, which causes trust issues in the beginning.”

Community canvassing to provide information and resources—meeting parents and families where they are—was an effective way to counter the false and negative narratives about teacher unions. The distorted media conversation around the return to school after the winter break this past January was partially based on a lack of understanding in the public about what teachers’ unions actually do. B2S campaigns are a good vehicle to educate the community before those false narratives take root.

While canvassing proved to be a vital campaign strategy, it also presented some challenges. For some affiliates, gaining access to reliable and accurate contact information for students who had left schools was a major challenge. This was especially true when the relationship between the union and school leaders was strained. Affiliates with a history of collaboration with district administrators were generally able to secure support for canvassing efforts, including sharing vital data to employ more-targeted outreach efforts.

Other challenges included a general reluctance by many members to knock on doors because of discomfort, fear for personal safety in some areas, or feeling overworked and lacking the time or energy. Some locals were able to overcome this challenge by incentivizing canvassing. Offering compensation was a good motivator. As for the discomfort of speaking with strangers, many noted that once teachers started talking to community members, they realized how enjoyable and valuable the process was. In essence, the experience itself became an intrinsic motivator for members to continue their involvement in canvassing. Addressing safety concerns, one affiliate partnered with a local political consulting firm to hire canvassers who lived in the community.

Our data suggest that some of these challenges varied based on the demographic composition of communities. For example, school districts serving mostly students of color were more likely than districts serving mostly white students to report inadequate economic resources as a major challenge. Teacher shortages were a major concern mainly among districts with majority-Latinx student populations and majority-Black student populations, which were about 30 percent and 19 percent, respectively, more likely than majority-white districts to report serious issues with teacher staffing.

Takeaways from B2S 2021

In the survey, 86 percent of grantees reported that their campaigns were successful. Of that number, 24 percent said the campaigns were highly successful. Looking at these successes as well as the many challenges that teachers faced during their campaigns, we identified several key takeaways that can inform future back-to-school campaigns.

Engage the Community

Community engagement was a central piece of most B2S campaigns. As retired teacher Hobie Hukill of Alliance/AFT in Dallas told us: “We saw this as an opportunity to make contact with the community—the folks in the neighborhood who are almost always overlooked—to begin a dialogue and sustained community connection.” Like many others, their campaign’s goal was to establish the union as a reliable and well-recognized resource for the school community and to demonstrate that teachers are on their side.

Rochester teacher Molly Bianco said, “Our goal was to get into the community, build those connections, and see where the needs are for our kids and our families.” Considering the new hardships for students and families that were created by COVID-19, Bianco said she wanted to show “how teachers and the schools can be a foundational point for resources and any type of support the family needs.”

Some of the major benefits of community engagement reported by B2S grantees included countering misinformation, building trust among parents and the community, improving perceptions of the union, building power, and increasing support for public education more generally. One grantee shared: “When teachers were coming to their doors and helping them, providing good information, we were able to counter some of the misinformation that was out there.”

By meeting parents where they were and listening to their needs and wishes, many locals were able to build new levels of trust in their communities. This of course improved public perceptions of the union. In the case of Aldine, Texas, the campaign effort created a new sense of openness and shared interests. As one respondent told us, “We actually had to turn people away because they wanted to join the union—not knowing they had to be teachers to join.”

Across most campaigns surveyed, leaders felt that students and parents were incredibly grateful for having a teacher check in on them and ask about their experiences. According to one leader from a higher education local, their greatest moment was “joining with fellow phone bank volunteers to call students who were shocked that a faculty member was actually calling them to check in and see if they were okay, to say they were concerned about and missed them, and to offer assistance in getting them back to their career path.” Beyond surprise and gratification, their phone banking resulted in 18 percent of the targeted students reenrolling.

Witnessing parents become more engaged was also a notable moment for many campaigns. As one respondent said, “Hearing from parents how much they appreciated the extra effort in reaching out to make sure this year was off to a good start truly encompasses why we applied for the grant.” Rochester teacher Gia Vallone told us: “A lot of families were shocked that teachers were taking the time out of their summer to do this. They were super grateful. Families just honestly wanted to be heard.” Reporting how the community responded positively to their outreach efforts and how well-attended their events were, one campaign leader told us their enrollment ultimately ended higher than pre-COVID-19, “with families moving to our district because of our engagement with the community.”

Having experienced the value of community engagement, many respondents advocated strongly for incorporating it into the union’s regular work going forward. As one respondent said, “We must get into our communities more and talk to parents at their doorsteps instead of thinking they will meet us at ours.”

Albany Public School Teachers’ Association (APSTA) President Laura Franz said it reminded her of the importance of making connections between the work teachers do and the people they serve. She said they plan to be more intentional about creating the time and space for community engagement moving forward. According to another survey respondent, “When we seek to serve others first, and seek ways to share our knowledge, material resources, and union social capital with those most in need, the people will respond in kind.”

Through this work, B2S campaigns offered many grantees an opportunity to see the shared interests they have with their community members as well as the long-term value of taking a social-movement approach to organizing and bargaining. For example, San Antonio Alliance President Alejandra Lopez explained that her local has been pursuing a “bargaining for the common good” approach in recent years and that the B2S campaign further reinforced their resolve to build strong community partnerships. “We don’t have collective bargaining, but we still follow that model. We have been working in solidarity with community organizations and building up those relationships.”

The San Antonio Alliance worked closely with community partners to develop a platform that informed their school board election efforts. “We had a massive canvassing program. We had field organizers out knocking on doors using a script that was much more rooted in a concrete vision for transformation in our district,” Lopez explained. These efforts have begun to build real power as indicated by the victory of their preferred candidate in the local school board election and the establishment of an Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief stakeholder committee. “We’ve been consistent with our message,” she added. “Nothing about us without us. Any decisions that are being made in this district should be made with workers, students, parents, and community.”

Community engagement has been an essential element of the labor movement from its inception—from the sit-down strikes of the 1930s9 to the farmworker strikes in the 1960s10 to the recent teacher strikes.† In fact, many of labor’s greatest victories have in some way depended on strong community support and often consisted of demands that reflected the values and needs of the whole community.11 This should come as no surprise because union members are also parents, homeowners or renters, taxpayers, neighbors, and community members.

Community-engaged campaigns like B2S can tap into all of those identities and their associated hopes and dreams, instilling a sense of pride among members as they fight not only for themselves and their coworkers but also for and in partnership with their neighbors and the broader community. In sum, community engagement is essential work for all unions, but perhaps especially so for teachers’ unions, whose position in society offers tremendous opportunities to promote equity and further the causes of economic and social justice.

Start Early

The most common response we received when asking campaigners what they would do differently next year was this: start earlier.

A majority of respondents wished they had more time to plan their campaigns. This sentiment was also echoed by many participants in the case study interviews. Given the constraints caused by the pandemic, all of the campaigns we examined still conducted impressive and groundbreaking work in their schools and communities. However, looking forward, future campaigns can definitely benefit from pre-summer planning and member recruitment. Many leaders explained that it is much easier to recruit members for summer projects during the school year rather than after school lets out for the summer. Moreover, some locals also placed B2S campaign work within their larger strategic plan to regularly secure more member and community participation.

Organize Member-Led Campaigns

The B2S campaigns were largely member-driven efforts. According to APSTA President Laura Franz, “From a local leader standpoint, ... [B2S] offers pathways for members to get involved with the union that go beyond bargaining or directly confronting management. This is really a member-organizing opportunity that allows people to engage with both the community and the union. It can help build the bench of potential future leaders.” This is an important consideration, particularly for locals looking to build their members’ capacities and skills.

Many affiliates that did use paid staff leveraged that support to train members and collect data and information, keeping the focus on putting members out front because education professionals are the most well-positioned school district stakeholders to reconnect students and families with their schools and help the larger community understand the value of public education.

Recognizing that B2S works best as a member-driven effort, locals that did not have much experience with canvassing and other campaigning tactics sought staff support from their state or regional leadership for training and education. Many leaders we interviewed said that developing these skills for the B2S campaign is now part of a long-term effort to build a group of member leaders who can aid in future electoral and community organizing efforts.

Create Varied Opportunities for Involvement

We heard many times that canvassing was typically the most effective tactic, but it was often challenging to identify and recruit members willing or able to participate in door knocking or phone banking. This highlights the importance of offering myriad ways for members and supporters to get involved. Designing a comprehensive campaign with earned and paid media, social media, public events, data collection, and other efforts supporting the core canvassing activities creates a variety of opportunities to engage a broader set of members in the union efforts. Some are more artistically inclined, others more social, some analytical—these are all valuable skills, and the more hands involved in the work, the lighter the lift is for each.

Equally important is offering opportunities with varying levels of commitment. Our survey revealed that being overworked cuts across every sector of education, so providing a range of commitment levels helps members feel a sustainable balance among work, union, and personal life. Multiple respondents noted that this approach allowed members to engage at their own comfort level, perhaps just a few hours per week. Even if campaign work is taking place mostly during the summer, campaign leaders should also recognize that all educators need a break, especially during the pandemic.

Providing some compensation for campaign activities is also a good recruiting tool and helps support members facing layoffs or reduced hours. According to one survey respondent from an institution of higher education, “With low levels of full-time employment, college-proclaimed budget shortfalls, and related staffing shortages, ... our members ... are exhausted.... Being flexible in offering multiple small commitment opportunities on a number of projects was key. Being able to pay volunteers—most of whom were part-time faculty and staff—thanks to support from the AFT helped in volunteer recruitment efforts and most importantly helped these colleagues that were hit hard employment-wise during the pandemic.”

Engage All Stakeholders

Many respondents discussed the importance of engaging a diverse set of stakeholders—students, parents, support staff, and other school employees—to participate in campaign activities. Many campaigns emphasized the importance of involving students to help with canvassing, phone banking, and coordinating events. According to one leader, their greatest moment was “seeing our students emerge as organizers and leaders serving their communities [and] helping others meet basic needs such as food and water, school supplies, and sanitation supplies.”

The San Antonio Alliance had collaborated with students prior to COVID-19, and as a result, students naturally plugged right in to the B2S work. “We’ve been working in solidarity with students for a couple of years now. The students have organized themselves into a student coalition. And so we were very intentional about offering support. We offer our offices and backyard for them to meet. We’re not here to tell you what students want; we’re here to make sure students are at the table and meaningfully engaged,” said local President Alejandra Lopez. Education Austin’s staff director, Gail Buhler, shared that “voices of the parents, the community, and the teachers were being diminished. Our goal was to build up a committee of parents and community members that could work on not just return-to-school issues with COVID but also be sustainable and have more of a voice going forward on all issues.”

Engaging a broad set of stakeholders can help B2S organizers better deliver on the promise of a high-quality public education that serves the interests of their communities. Including the voices of parents, students, and other school staff can broaden the scope of demands that are made and also strengthen support for back-to-school efforts. As one survey respondent stated, it is “human interaction at its best—cooperation toward a common purpose.”

Build Year-Round Organizing Infrastructure

Most grantees said they hoped to extend the work they began with their B2S campaigns. One survey respondent said, “I honestly hope we can do this annually and offer as much as we can to our families and students. They deserve it!” Some grantees were following up with new and returning students during the school year to see how they were doing with attendance and participation in school. Others committed to make their fall festivals or B2S community nights annual events in partnership with their school administrations or are continuing their community outreach efforts to build their contact lists for next year and beyond.

The San Antonio Alliance incorporated B2S work into its strategic plan to ensure it isn’t forgotten or left to the last minute during the school year, when so many other pressing issues arise. Aldine AFT reported that “the work that has been done in this campaign was just the start, but now it’s time to help meet the needs of members, schools, students, and the community as a whole.”

Beyond continuing their B2S efforts, many spoke about the need for building a more permanent organizing infrastructure that could be operational year-round, including a bench of canvassers, strong ties with parents, and regular contact with the community. One survey respondent said, “We need more strategic and planned efforts to organize our communities. This must be continuous and ongoing.”

“We’ve been thinking about how to keep some of this going, because I think it’s important that we’re having conversations not just during the political times but outside those times and building those relationships,” said Zeph Capo of Texas AFT. He added that they were currently thinking about how to systematize their program with canvassing team captains as well as hiring and training retirees and training volunteers in order to function year-round. “That’s what we’re trying to think about now because those folks are really what allow you to have continuous improvement in your work.”

By always organizing, local unions can be better prepared for annual B2S efforts and for serving the needs of students, teachers, and communities throughout the year. For example, one respondent told us how the B2S effort helped their local become better organized for a later campaign in their district: “It gave us information to organize a subsequent campaign.... We used the data and internal organizing structures learned from the B2S campaign in order to be more efficient.”

This can be applied to school board elections, contract campaigns, legislative efforts, and more. In short, having a strong relationship with the community through year-round organizing can build real power to pursue the shared interests of the many stakeholders in the school community.

Collaborate with Management as Much as Possible

From Rio Rancho, New Mexico, to Lynn, Massachusetts, one of the biggest lessons from the 2021 B2S campaigns was the importance of collaboration between the union and school leadership. Locals that historically have had good working relationships with their school administration or school boards were able to quickly draw on those ties to make their B2S campaigns more effective. Hobie Hukill of Alliance/AFT in Dallas told us: “Compared to the difficulties they had with the administration in some other counties, I can say that [Alliance/AFT President] Rena Honea’s connection with the administration gave us credibility. Everything else was magnificent. We actually got lists from them, which other counties fought tooth and nail for several weeks to get. It’s just one of those things where face-to-face credible contact over time makes a difference.”

Having a collaborative relationship with the administration often meant the difference between access to reliable lists for canvassing versus creating lists from scratch that were typically less accurate or less focused. It also played an important role in access to school facilities and other resources that helped make various B2S campaign events possible. Several teachers in districts with more collaborative relationships told us how much the administration appreciated the plans the union initiated and offered support to achieve the shared goal of getting kids back to school.

Jackie Anderson, president of the Houston Federation of Teachers, described how the district had been attempting to do outreach previously, but its efforts were not very strategic, lacked a basic understanding of organizing principles, and, as a result, were ineffective. She said, “[the district leaders] were overjoyed when they saw that we had a plan for [distributing information] and for canvassing in the neighborhoods, and all we needed from them was to identify the areas where the most students were missing so we could actually make the calls, [drop off the informational literature], and canvass.” The district provided a space for phone banking and shared the necessary data for targeted outreach. “It was an experience for them to see how we organize—they did not know what real organizers do,” she said.

Countless other grantees described how the union had brought the plan, had the skills, and provided boots on the ground, while the administration was asked to provide data and sometimes facilities. A good collaborative relationship made a big difference when the time came to make this ask. Zeph Capo of Texas AFT told us, “There was clearly a definitive difference where districts were more collaborative with us, and we were working together closely—those were the districts where we were better able to close the gap, bringing more kids back to school.” A good example is the enrollment gap in Dallas, which decreased from 20 percent to just 8 percent, a reduction that was predicated on good union-district relations. Capo continued, “I do think this campaign demonstrates what success we can have when we’re in alignment—teachers and the Alliance/AFT working directly with the district for the betterment of the community, the kids, and families.”

In areas where the relationship between the union and the administration was antagonistic or strained, it was more difficult to identify and locate students whom the campaign was aiming to bring back to school. “Having access to that data would have made for a better campaign for us. We could have ... canvassed the people who said, ‘I’m not sending my child back,’ and instead we were ... just door-knocking families that we know were in the city schools,” APSTA President Laura Franz told us. With a more collaborative relationship, she said, “we could have made better use of our canvassing time and their social media resources and all the other things that the district could have supported us with.”

Many anonymous survey respondents indicated that their biggest challenge in the campaign was lack of cooperation from their school administration or school board. One respondent said, “Our biggest challenge was that our school district did not want to partner for the first nine weeks of the campaign, which meant that they did not share data for our canvassing program.” And another stated, “Most of our challenge depended on the willingness of the district to share data in order to reach the right families. A partnership with the district would have led to a more fruitful campaign.”

Some locals in this situation opted to go past superintendents and speak directly to school board members. According to one local, “Although it was initially frustrating that the superintendent would not partner with us, we learned that if we approached individual school board members and explained the benefit, ... we could get support for our initiative.” Others confronted the challenge by using public voter registries or existing lists the union had generated for previous campaigns.

Many locals that took this approach expressed that, despite not always directly targeting families who had disconnected from schools, it was still useful for the union to connect with the broader community. This broader targeting strategy also proved to be particularly useful for unions in districts facing intense competition with charter schools, many of which regularly engage in similar canvassing strategies to market their schools to families.

Given how critical union-management collaboration seemed to be to the success of B2S campaigns, some locals saw their campaign as an opportunity to hit the refresh button on their relationship with their district leadership and demonstrate that the union can be a real partner in reaching out to the community. According to one respondent, “One of our goals was to have a better and more trusting relationship with our central office. We are constantly reaching out to them to see how we can support enrollment, school immunization, and vaccination clinics.”

Another local said that staying in touch with relevant stakeholders from the district was critical to overcoming challenges that their campaign faced: “We maintained positive communication with members and all stakeholders, working with the superintendent.”

The campaign in San Antonio sought to build greater trust with the school board as well, which by most accounts has historically been very anti-union. According to recently elected union-backed school board member Sarah Sorensen, the efforts did help to build some bridges. “I actually am very hopeful,” Sorensen said, “that this shifts the tone in terms of the way that the board, the union, and the administration work together so that there will be a positive relationship. And I am excited to see what opportunities will grow out of this.”

San Antonio Alliance President Alejandra Lopez agreed: “We have historically had a very antagonistic relationship with the school board members.... It was a real shift for them to be thanking the union for knocking on doors to get people to the vaccine town hall.”

In some cases, a recent change in district administration had opened an opportunity to build new and better relationships or to work collaboratively for the first time with a less antagonistic administration. Commenting on a recent shift in her district, Shannon Adams, president of the Martinsville Classroom Teachers Association, said, “I hope administrators read this. When we all get in it together, and we put all of the other stuff aside, great things happen for our people and our kids.... If we want to save public education, that’s what it takes. If teachers aren’t organized, they need to get organized and stick together, start working on their collective voice, and then be cooperative participants in moving forward. It’s the only way we protect public education for the community.”

Even for locals that were not able to establish a good working relationship with management last year, many expressed an eagerness to go back to their administrations this year. They plan to highlight the successes of their campaigns and begin a fresh conversation about how much more could be done to engage with families and the community if management and labor work together.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created—and continues to create—tremendous challenges for educators and educational institutions alike. But teachers and their unions have confronted these challenges head on, adapting their practices, advocating for their members and students, and fighting to ensure the best possible education for all.

To this end, the AFT has consistently urged school leaders and other public officials to follow the science on safety measures. “When science and evidence speak, we listen,” AFT President Randi Weingarten has said in several news media interviews. Public health mitigation strategies—most especially vaccination—are essential for safe in-person schooling. And in-person learning is essential for providing high-quality instruction and supporting the social and emotional development of our children from pre-K through young adulthood.

Through the AFT’s Back to School for All campaign, teachers have begun to build stronger relationships with the communities they serve. Countering misinformation about vaccines and school safety, they have done what teachers do best: educate. Providing vaccine clinics and material resources in underserved communities, they have helped support social justice. And advocating for common-sense safety measures while welcoming students back to school, they have helped to create safe, nurturing learning environments and to reassure families.

There is still much work to be done, and many of the same challenges still exist as we prepare to start another school year this fall. The B2S campaign provides great examples of the work that is needed to rebuild support for and participation in public schools, colleges, and universities. The single most important step any affiliate can take right now is to begin making a plan and pulling together a team to do the vital work of community engagement. This is no longer just an option; it is an essential piece of union work.

Todd E. Vachon is an assistant professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers University, the director of the Labor Education Action Research Network (LEARN), and an American Federation of Teachers New Jersey vice president for higher education. Kayla Crawley is a sociology PhD candidate at Rutgers University examining the intersection of race, education, and school policy, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on school discipline practices. James Boyle is a master's student in labor and employment relations at Rutgers University; he also assists in research projects for the Education and Employment Research Center at Rutgers and LEARN.

*Grantees are quoted throughout this article. When individuals are not identified, the quotes come from anonymous survey responses. (return to article)

†To learn more about recent teacher strikes, see “Organizing and Mobilizing: How Teachers and Communities Are Winning the Fight to Revitalize Public Education” in the Spring 2021 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. US Department of Education, “Supporting Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Maximizing In-Person Learning and Implementing Effective Practices for Students in Quarantine and Isolation,” ed.gov/coronavirus/supporting-students-during-covid-19-pandemic; A. Duckworth et al., “Students Attending School Remotely Suffer Socially, Emotionally, and Academically,” Educational Researcher 50, no. 7 (July 13, 2021): 479–82; and C. Halloran et al., “Pandemic Schooling Mode and Student Test Scores: Evidence from US States,” NBER Working Paper No. 29497, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2021.

2. R. Weingarten, “Where We Stand: Reopening Schools Means Prioritizing Safety for Students and Staff,” American Educator 45, no. 3 (Fall 2021): 1.

3. Weingarten, “Where We Stand.”

4. National Center for Education Statistics, “Nation’s Public School Enrollment Dropped 3 Percent in 2020–21,” US Department of Education, June 28, 2021.

5. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “Overview: Fall 2021 Enrollment Estimates,” nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/CTEE_Report_Fall_2021.pdf.

6. K. Kricorian and K. Turner, “COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Beliefs Among Black and Hispanic Americans,” PLOS ONE 16, no. 8 (2021): e0256122; and G. Sanchez et al., “Discrimination in the Healthcare System Is Leading to Vaccination Hesitancy,” Brookings (blog), October 20, 2021.

7. N. Feldman, “Why Black and Latino People Still Lag on COVID Vaccines—and How to Fix It,” National Public Radio, April 26, 2021.

8. L. Phillips et al., “Surveying and Resonating with Teacher Concerns During COVID-19 Pandemic,” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, published online October 20, 2021; Sykes Enterprises, “2021 Teaching Survey: K–12 Teachers Are (More) Overworked During Pandemic,” 2021, sykes.com/resources/reports/2021-teaching-workload-during-pandemic; E. Steiner and A. Woo, Job-Related Stress Threatens the Teacher Supply: Key Findings from the 2021 State of the U.S. Teacher Survey (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021); and Fidelity Investments and the Chronicle of Higher Education, “On the Verge of Burnout”: Covid-19’s Impact on Faculty Well-Being and Career Plans (Washington, DC: Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020).

9. To learn more, see E. Loomis, A History of America in Ten Strikes (New York: The New Press, 2018); C. Smith, “The Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936–1937: Remembered in Oral Histories by the Participants,” Perspectives on Work 19, no. 1 (2015): 34–37, 88–89; and Sloan Museum, “The Flint Sit-Down Strike,” Flint Cultural Center Corporation, sloanlongway.org/flint-sit-down-strike.

10. To learn more, see M. Ganz, Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009); and L. Flores, Grounds for Dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the California Farmworker Movement (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).

11. C. Calhoun, “ ‘New Social Movements’ of the Early Nineteenth Century,” Social Science History 17, no. 3 (1993): 385–427; and J. Pope, “Labor-Community Coalitions and Boycotts: The Old Labor Law, the New Unionism, and the Living Constitution,” Texas Law Review 69, no. 889 (1991): 901–4.

[Massachusetts photos: Marilyn Humphries, courtesy of AFT Massachusetts; all other photos: AFT]