On Sunday, October 28, 2012, teachers across the Northeast were glued to their television sets to watch the latest weather forecast about the approaching hurricane. Schools would be closed Monday. Emergencies were declared, line crews were summoned, shelters were prepared, and command centers were opened. New York City made the unprecedented decision to stop all subway service.

As feared, Superstorm Sandy arrived with a vengeance the next evening, knocking out power for eight million people across 17 states, destroying countless homes, rendering the NYC subway system nonoperational, and closing all 1,750 of the city’s schools for a week. Dozens of damaged schools remained shuttered even longer, forcing students to share buildings with other schools, sometimes in distant boroughs of the city. Over 100 deaths were attributed to the storm, including at least one teacher. As with previous extreme storms such as Hurricane Katrina that hit the Gulf Coast in 2005 or later storms like Hurricane Maria that ravaged Puerto Rico in 2017, it was the working class and poor—the frontline communities—who were hit first and worst.

Nine years later, New York and New Jersey were devastated again by Hurricane Ida while still continuing to shore up infrastructure ruined by Sandy. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration places the total cost of Superstorm Sandy at over $70 billion1—possibly the costliest to ever hit the region, making it the most economically devastating event to hit New York City since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

While individual weather events like Sandy cannot be directly attributed to climate change, their likelihood, frequency, and intensity are all increased by climate change. As the Earth warms, storms that used to happen once a century are now happening more frequently, and the impacts on students, teachers, and communities are devastating.2 This article explores some of the causes of the climate crisis, including its relationship to social and economic inequality, and what educators can do—and many already are doing—through their unions to promote climate justice and equity in their schools and communities. Perhaps your local union will be the next to take bold climate action and become a part of the solution by helping to forge your own local Green New Deal and joining the national effort.

The Problem: Dual Crises of Ecology and Inequality

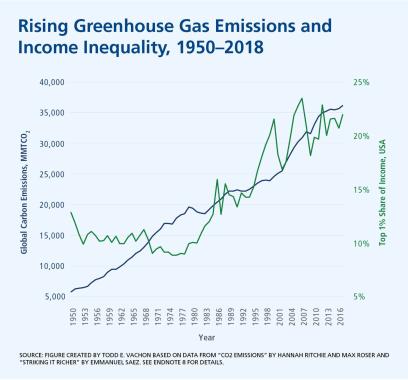

The world is in the midst of two simultaneous and interconnected crises: a crisis of ecology and a crisis of inequality. Climate change is negatively affecting human health and quality of life and is disproportionately impacting marginalized populations. At the same time, socioeconomic inequality has increased dramatically. The top 1 percent of earners now take home 22 percent of all income in the United States, the top 10 percent own 70 percent of all wealth, and real wages for American workers have been stagnant for decades.3 These economic disparities are amplified along the lines of race, gender, and citizenship status.

Climate change is caused predominantly by the burning of fossil fuels such as oil, gas, and coal, which emit greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere, causing the planet to warm.4 As the planet warms, local climates are altered, leading to more frequent and intense storms, more wildfires and droughts, accelerated melting of arctic ice, rising sea levels, and the mass extinction of species that cannot adapt rapidly enough to the rate of climatic change.

Rising economic inequality is due to a variety of factors, including declining unionization; tax cuts for the super-rich; labor market deregulation; the replacement of full-time, permanent jobs with part-time and temporary work; a weak social safety net for working families; and the increased financialization of the US economy.5 All of these factors accelerated around 1980 with the rise of free market fundamentalist (aka neoliberal) leadership in the federal government.6 Rising inequality* has been associated with increased social and health problems, lower life expectancies, decreased child well-being, a decline in trust in public institutions—including schools and governments—and an erosion of support for democracy itself.7

The figure below illustrates the simultaneous rise of GHG emissions and income inequality between 1950 and 2018. Global emissions increased more than sixfold during this period, from just under 6,000 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (MMTCO₂) in 1950 to 36,000 MMTCO₂ in 2018.8 At the same time, the share of all income earned by the top 1 percent of earners in the United States more than doubled from a low of 9 percent in 1978 to over 22 percent in 2018.9 According to Oxfam, the world’s top 26 billionaires now own as much as the poorest 3.8 billion people on Earth, and the richest 10 percent of humans are responsible for nearly half of all carbon emissions caused by consumption.10

In addition to consuming considerably more than the average person, many billionaires derive their wealth directly from owning fossil fuel corporations, many of which have funded climate change denialism to prop up their corporate profits.11 Billionaires of all backgrounds also invest heavily in financial instruments that promote the extraction, production, transportation, and consumption of fossil fuels. A 2022 report from Oxfam finds the investments of just 125 billionaires produce 393 MMTCO₂ emissions every year.12 That’s equal to the total emissions generated by the country of France. On average, one billionaire’s investments’ annual emissions are a million times higher than a person in the poorest 90 percent of the world’s population.13

Many of these same billionaires have also spent large sums of money combating union drives as well as influencing politics to weaken labor protections. In other words, many of the top contributors to the climate crisis are also the strongest anti-union forces and promoters of policies such as “right-to-work” laws, which reduce worker power, suppress wages, and increase income inequality.14 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, just 10.1 percent of US workers are currently represented by a union—down from a high of 35 percent in 1953. The number is even lower when looking at the private sector, which has a unionization rate of just 6.1 percent.15 Much of the decline has been due to the erosion of jobs in the once highly unionized manufacturing industry and the massive increase of employment in industries that are not highly unionized due to weak labor laws and vigorous anti-union campaigns by hostile employers, as we have seen with Amazon and Starbucks.16

At the same time, as a result of the legacy of racism and discriminatory hiring practices, workers from historically marginalized communities, particularly Black and Latinx workers, have been systematically deprived of opportunities to share in the prosperity generated by the fossil fuel economy. Adding insult to injury, these same workers have disproportionately borne the burden of the pollution created by the fossil fuel and other toxic industries.17 For example, a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that air pollution exposure in the United States is disproportionately caused by the non-Hispanic white majority but disproportionately inhaled by Black and Hispanic minorities.18 On average, non-Hispanic white people experience a “pollution advantage” of about 17 percent less air pollution exposure than is caused by their consumption, while Black and Hispanic people, on average, bear a “pollution burden” of 56 percent and 63 percent excess exposure, respectively.

Students, educators, schools, and universities are not immune to the consequences of unchecked climate change and runaway inequality. A study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that a 1-degree-Fahrenheit hotter school year reduces that year’s learning by 1 percent and that hot school days disproportionately impact students of color, accounting for roughly 5 percent of the racial achievement gap.19 Each fall, during the height of hurricane season, extreme weather increasingly disrupts back-to-school plans across the country, with closures affecting more than 1.1 million students in 2021.20 In 2022, the US Government Accountability Office released a report on the impacts of weather and climate disasters on schools, finding that over one-half of public school districts—representing over two-thirds of all students across the country—are in counties that experienced presidentially declared major disasters from 2017 to 2019. Recent research in the journal Scientific Reports finds that school closures due to wildfires in California generate significant negative impacts on academic performance among students.21 The connection between the increasing number of hot days and disaster-related school closures and lost learning are just two examples of how climate change is already affecting education.22

The impacts of unmitigated climate change also cause severe damage to educational infrastructure. A 2017 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that nearly 6,500 public schools are in counties with a high risk of flooding, and a study in the journal Nature found that the nation’s flood risk will jump 26 percent in the next 30 years.23 An assessment by the Center for Integrative Environmental Research at the University of Maryland finds that extreme weather events, such as flooding and wildfires, place immense strain on public sector budgets at the state and local levels.24 Such budgetary constraints put considerable stress on school budgets and create significant challenges for unions going into bargaining over wages, hours, and working conditions for their members.

Between Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the West Coast wildfires of 2022, there were over 200 “billion-dollar weather and climate disasters,” totaling over $1.8 trillion in damages.25 As disasters become more frequent and more forceful, there is an increased understanding that the impacts are unequal. Schools and communities across America have testified to the ways disasters compound, cumulatively increasing inequality and disadvantage. The good news is that there is an important role that students, educators, our local unions, and community allies can play in addressing the dual crises of climate change and inequality.

The Solution: A Just Transition

The extreme inequality and poverty in our very wealthy society are morally reprehensible. They are also the result of decades of intentional policy decisions that have concentrated income, wealth, and power in the hands of fewer and fewer people, who then use that money and power to further expand their money and power. In short, the current rules of the game are not designed to ensure the greatest good for the greatest number of Americans, but rather to ensure the greatest profits for the wealthiest and most powerful Americans. Reversing this trend and centering the common good—putting all people’s economic, social, mental, and physical health before corporate profits—will require significant changes to the way our economy operates. Confronting the climate crisis offers a potential pathway for making some of the important changes in our economy that are needed to recenter the lives and well-being of people. We can right economic wrongs and create good jobs with fair wages and benefits while “going green,” but only if we now make intentional policy decisions that focus on equity, inclusion, and justice.

The concept of a “just transition” attempts to do just that by reducing fossil fuel dependence while simultaneously investing in communities and people by creating good job opportunities that offer living wages, health and retirement benefits, opportunities for promotion, and union representation for displaced and historically marginalized workers. The idea originates from the work of the late American labor and environmental health and safety activist Tony Mazzocchi of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers union.26 Broken into its constituent parts, “transition” refers to “the passage from one state, stage, subject, or place to another,” and “just,” in this usage, is the root word for “justice,” meaning “acting or being in conformity with what is morally upright or good.”27 In other words, a just transition combines the often-conflicting projects of economic transition and the pursuit of social justice into one unified endeavor.

When confronting the problem of climate change, the potential for injustice is great, particularly if decisions are made solely by economic elites and grounded in the logic of neoliberal capitalism. This logic of unregulated free markets has led to the accumulation of wealth at the top while working- and middle-class families struggle, and it is at the root of the false choice between having good jobs or having a healthy environment that many blue-collar workers are confronted with.28 The same logic has led to the construction and operation of polluting facilities in poor and predominantly nonwhite communities across the United States, while historically excluding the very same populations from access to the job opportunities within or only offering the most dangerous occupations to local workers of color.

The very notion of a just transition challenges the powerful neoliberal ideology that has dominated US governance since the late 1970s. It instead offers a vision of economic democracy, including public investments to account for the full social costs and benefits of environmental and economic policies to create the most just—not necessarily the most profitable—outcome for all. Instead of offering a false choice between good jobs and a healthy environment, a just transition puts people before profits by pursuing both clean air and good jobs at the same time. The education sector has a large role to play in creating a just transition, not only through teaching and learning but also by transforming our facilities and operations to address climate change and in the process creating good career pipelines and reducing inequalities.

As educators, we have a responsibility as the stewards of the next generation to help ensure that we pass along a livable climate with a fair economy to our students and all future generations. It is for this reason that the AFT has adopted several resolutions on climate change in recent years, including “A Just Transition to a Peaceful and Sustainable Economy” (2017),29 “In Support of Green New Deal” (2020),30 and “Divest from Fossil Fuels and Reinvest in Workers and Communities” (2022).31 Nationally, at the state level, and locally, the AFT, in partnership with student activists and community groups, has been a leader on confronting the climate crisis, but still more can and should be done to promote a truly just transition. I spoke with a dozen educators and students from around the United States who have been engaging in this work through their unions and in their schools and universities. These conversations inform the recommendations outlined below.

Pursuing a Just Transition in the Education Sector

Like all sectors, public schools, colleges, and universities have played their part in contributing to climate change. According to the Aspen Institute, there are nearly 100,000 public preK–12 schools in the United States. They occupy two million acres of land and emit 78 MMTCO₂ annually32 at a cost of about $8 billion per year for energy. Our public school buildings are about 50 years old, on average, and far too many operate outdated and inefficient HVAC equipment, have poor insulation, and have electrical and plumbing systems in desperate need of repair.33 While the problem is widespread, it is even more pronounced in low-income communities and communities of color.34 Public schools also operate the largest mass transit fleet in the country with nearly 480,000 school buses on the road.35 There are an additional 6,000 two-year and four-year public higher education institutions throughout the United States that are also in need of energy efficiency improvements.36

Given their environmental impact, schools, colleges, and universities are an excellent place to begin forging a just transition through investments in green schools that would reduce GHG emissions and pollution exposure while creating good jobs that can address systemic inequalities along the lines of race, class, and gender. This involves installing renewable energy generation and storage systems, renovating existing school buildings to improve efficiencies, constructing new green buildings, securing strong labor standards, ensuring an open and democratic process for all stakeholders, and requiring local and preferential hiring to ensure that local communities and displaced workers benefit from the jobs that are created in the process.

Constructing Healthy Green Schools

So what are the elements of healthy green schools? Green school projects include installation of solar panels or other renewable energy sources; improving heating, cooling, and ventilation systems (e.g., installing heat pumps); constructing new energy efficient buildings or making retrofits to existing buildings (e.g., new doors, windows, and insulation); installing battery storage for renewably generated electricity; creating microgrids that can support communities during power outages; modernizing lighting; switching from diesel to electric vehicle fleets; automating building systems (including smart thermostats and sensors for lights and faucets); and creating more green spaces.37 These investments not only reduce the carbon footprint of schools but also save money on energy costs and reduce unhealthy pollution.38

These sorts of investments are not cheap. To cover the costs of these investments, Representative Jamaal Bowman and Senator Ed Markey have introduced Green New Deal (GND) for Public Schools legislation that would invest $1.6 trillion over 10 years to fund green upgrades—but that bill is not yet passed.39 Thankfully, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which was passed in 2022, offers many incentives for local schools to make these upgrades now while we continue to fight for GND for education.40 In particular, the AFT and other nonprofits lobbied for the inclusion of “direct pay” incentives in the bill that allow tax-exempt entities such as local governments, school districts, universities, nonprofits, and unions to receive direct rebates, in lieu of tax credits, from the federal government to cover a significant percent of the cost of green school projects.

The IRA incentives are like grants equal to at least 6 percent and up to 60 percent of any renewable energy project’s cost. However, unlike regular grants, there is no competitive application process. If a school district makes an appropriate investment, the IRS will wire them money. The credits are applicable to the cost for fuel cells, solar systems, small windmills, qualified offshore wind, geothermal heat pumps, and energy storage. Projects that pay the local prevailing wage and hire apprentices from locally approved apprenticeship programs qualify for a 30 percent credit. Projects that meet the domestic content requirement earn an additional 10 percent credit. Projects in energy communities41 or low-income communities can earn up to an additional 10 percent credit each.42

With direct pay, schools, colleges, and universities can own their clean power and maximize their cost benefits in the long run by keeping 100 percent of the savings. The rebate can be used to pay off huge portions of the project immediately, and the utility cost savings from self-generation of electricity in the long run can be used to pay off the balance.

The important thing to note about green school projects is that they must be initiated locally, through local budgeting processes, including bonding discussions, municipal capital budgets, and referenda. Education unions are strategically positioned to lead in this effort. In many cases, they already are—as we’ll see below.

Confronting Social and Economic Inequality

Combating the dual crises of ecology and inequality requires prioritizing environmental and climate justice to secure an equitable distribution of environmental burdens and benefits. For example, lead in public water supplies is a tremendous health hazard to students and residents in frontline communities from Newark, New Jersey, to Flint, Michigan, and beyond.43 In these communities, workers and community activists can together advocate for the repair or replacement of poisoned water pipelines and demand the cleanup of the groundwater and aquifers that feed those pipelines. Education unions and community members can also demand the electrification of vehicles to reduce student and worker exposure to asthma-causing particulate matter pollution and reduce GHG emissions.

Creating more green spaces in urban communities or constructing bike paths or walking trails can reduce auto traffic around schools, colleges, and universities. Community-owned solar, microgrids, battery storage, and resilience hubs are key ingredients to equitable climate resilience. When the regional power company’s grid goes down, schools, colleges, and universities, as local anchor institutions, can provide a safe space—known as a resilience hub—for the provision of potable water, electricity for charging medical and communication devices, refrigeration for medications, and other vital services needed to save lives during climate catastrophes such as hurricanes. These facilities are most effective when the solar power is “islanded” within a microgrid, meaning it can be stored and used locally rather than being transmitted onto the regular electrical grid (which is how net-metering works in many states and localities).44

Climate equity also means pursuing labor justice and ensuring that the new jobs created are good jobs, providing opportunities not only for workers from historically marginalized communities but also for those displaced from the fossil fuel industry.

As noted above, the IRA promotes strong labor standards by providing additional incentives for projects that offer prevailing wages, take apprentices from qualified apprenticeship programs, and use domestically manufactured materials. Prevailing wages take labor costs out of competition in the construction bidding process, giving high-road union employers a better chance of securing contracts to retrofit old schools or build new green schools. Apprenticeships create a career pathway into well-paying jobs without the burden of debt that most students accrue pursuing college degrees. Sourcing building materials from domestic manufacturers also helps to support local manufacturing job opportunities. AFT locals, in partnership with construction and manufacturing unions and other community partners, can use all of these tools to ensure good jobs are created in the process of greening our nation’s schools.

Perhaps most importantly, to truly advance equity and justice through a just transition plan, all voices must be equally included in decision-making. Social and economic justice campaigners operate under the simple principle that “Nothing about us, without us, is for us.” It means that decisions that significantly impact people’s lives cannot be fair and just without first listening to those people and empowering them to participate in the decision-making process.

Teaching Climate Justice

As teachers, we know the power of education. Through our lessons in preK–12 schools, colleges, and universities, we are uniquely positioned to develop, engage, and prepare the next generation to be equipped to address climate change and to succeed in the green economy of the future. As the Aspen Institute’s K12 Climate Action Plan states, “Educators across subject areas in school and in out-of-school programs can support teaching and learning on sustainability, the environment, green jobs, and climate change and empower students with agency to advance solutions.”45 However, as Betsy Drinan of the Boston Teachers Union (BTU) climate justice committee said to me, “It’s not just that greenhouse gases warm the planet and that causes these changes. It’s also the history of energy use that caused all this inequality and the impacts of climate change cause further inequality.”46

That is why developing and teaching climate justice curriculum, as opposed to just climate change curriculum, is an important piece of a just transition. The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) has already begun developing content with a strong focus on climate justice and equity.47 The BTU is considering doing the same. As Betsy told me, how we address climate change can either reduce or exacerbate inequality. Some key questions for educators and students, she said, are: “Who has the power in these decisions? How are they using that power? And who are they keeping out of those decisions? That is what will determine the outcome.”48 Ayesha Qazi-Lampert from the CTU climate justice committee agreed and added that “climate literacy is also an organizing tool; the education reveals inequities that inspire efforts for change—it’s kind of a cycle.”49

A good starting point for interested teachers is Aaron Karp’s “Educating for Climate Activism, Autonomy, and System Change,” which lays out a curriculum model that contains five content areas that aim to analyze the major forces that give rise to today’s existential problems and their solutions: ecological systems, energy sources and technology, economic institutions, power structures and politics, and social movement–driven societal change.50 The model envisions the development of literacy in each area, including their interconnections, and could be used to guide curriculum development for educators as well as courses in teacher education.

Investing in Career and Technical Education

A just transition to a more sustainable and equitable future is going to require a massive influx of skilled workers to do all of the new jobs, especially in the skilled trades initially, but in other technical occupations thereafter. An investment in career and technical education (CTE) is an investment in the future, especially when it is infused throughout the entire school curriculum, dismantling the false disconnect that has often existed between academic learning and skills training. Incorporating CTE into all areas of the curriculum can create an important link between the world of school and the world of work that can motivate students to continue their education while giving them the knowledge and flexible skills that will make it possible for them to adapt to the jobs of the future.

A great example of this approach can be seen in the Peoria Public Schools system in Illinois. In 2015, the Peoria Federation of Teachers and the Greater Peoria Works campaign utilized funds from the Illinois Federation of Teachers and from an AFT Innovation Fund grant supporting the Promising Pathways initiative to modernize CTE programs.51 Among the dozen new CTE programs offering industry-recognized credentials, Peoria created a two-year renewable energy training program. And when the school installed solar panels on the roof of the building, the program worked closely with the installers to integrate the process into the curriculum with students learning everything from solar installation techniques to the monitoring of energy use and generation.

Investing in CTE like Peoria and other school districts have done allows students to learn and prepare for good jobs. Scaling successful programs so as many students as possible can take advantage of them, and move on to success in careers and life, is an important step in ensuring a just transition.

Making It All Happen

Forging a just transition in education with healthy green schools and social and economic justice requires grassroots organizing and power building. Some important steps include forming local union climate justice committees, building strong partnerships with students and community groups, bargaining for the common good, and holding decision makers accountable. These local efforts can also be coordinated nationally for maximum impact across the entirety of the education sector.

Form Local Union Climate Justice Committees

As democratic organizations, unions rely on membership resolutions to lay out positions on issues and on committees to push forward plans of action on those issues. The same is true with climate justice work. In my own research, I have found that most teacher-initiated climate action currently underway around the country is being led by members of unions that have adopted climate resolutions and formed local union climate justice committees to advance the unions’ work on the issue.52 Forming a climate justice committee does two things. First, it ensures that the issue of climate justice remains on the union’s agenda. Second, it creates a space for interested members to engage with the issue within their union and help to drive the union’s climate work at the grassroots level. It is difficult to overstate how important a climate justice committee is for any union that wants to begin engaging in climate justice work. The more such local committees that exist, the more local unions there will be pushing a climate justice agenda within their school district, college, or university, amplifying the positive impact.

Partner with Students, Community Allies, and Other Unions to Push for Change

To win a just transition for education, our local unions must forge deep partnerships with student activists, environmentalists, environmental and climate justice groups, parent/caregiver organizations, and other unions in different industries. Many education unions have already been engaging in this work, including United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), which has more than a dozen community partners with whom it is making climate justice demands at school board meetings and in bargaining.

College and university professors from local unions around the country have joined with students in climate strikes demanding an end to fossil fuel use by universities. In the summer and fall of 2019, after passing a local union Green New Deal resolution, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP)-AFT local at Rutgers University in New Jersey worked closely with student groups and community partners to organize a massive climate strike. As James Boyle, a student who helped organize the strike, said, “We need to acknowledge that climate change involves limits,” especially when it comes to energy consumption and waste generation.53 On September 20, 2019, faculty, staff, students, and community members rallied and marched together, demanded, and ultimately won commitments from the university in the following months to divest from fossil fuels and develop a strong climate action plan with timelines and targets for phasing out fossil fuel use. The coalition also emphasized the importance of using local union labor to do the construction work involved in the transition. Three years later, faculty, students, and community members came together again for a second climate action, demanding the university move more rapidly to transitioning away from fossil fuels and installing community solar and resilience hubs. Following the action, student leader Alexa Haris said of the coalition, “We need to talk about what other actions we can pursue, such as camping out on university property, holding sit-ins, and attending city council meetings and university board of governors meetings.”54

In addition to helping to organize the climate strikes and winning fossil fuel divestment, members of the Rutgers AAUP-AFT climate justice committee were also involved in designing the university’s climate action plan, which calls for achieving carbon neutrality by 2040. To help achieve this goal, union members have been organizing with environmental justice and community groups in Newark, Camden, and New Brunswick to educate the public about the benefits of community solar and advocating for the university to open up its rooftops and parking lots to accommodate it. Other members of the climate justice committee have partnered with environmental organizations to oppose dangerous and polluting fossil fuel projects such as the proposed liquid natural gas export terminal in Gibbstown. As climate justice committee member Jovanna Rosen said in an op-ed opposing the project: “Our faculty and graduate worker union at Rutgers believes in ‘bargaining for the common good,’ [which is] a labor strategy that builds community-union partnerships to achieve a more equitable and sustainable future.”55

Other unions, especially in the building trades, are vital partners when pursuing green school initiatives. Recently, educators in Washington state worked with the local building trades unions to successfully win support for increased funding for school retrofits.56 Nationally, through the Climate Jobs National Resource Center (CJNRC), and in many states, educators and construction trades unions have been working together to win support for green infrastructure projects, including schools. For example, Climate Jobs Illinois, a state affiliate of the CJNRC with 14 member unions, has a community-driven Carbon Free Healthy Schools campaign to invest in Illinois’s public schools through energy efficiency upgrades and solar power systems. These healthy schools will save school districts millions in energy costs, decrease emissions that contribute to climate change, offer opportunities for more CTE programs in green energy, and create thousands of union jobs.57

At the national level, the AFT and the United Auto Workers are calling on school districts to electrify the nation’s school bus fleet.58 Cities and counties can use seed money provided by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to accelerate the rollout of union-built electric school buses. There are about half a million yellow school buses operating across the United States, generating more than five million tons of GHG emissions every year59 and emitting pollutants that increase the likelihood of asthma and other respiratory conditions among students, drivers, and community members—especially in low-income communities that have suffered disproportionately from environmental injustice.60 At a press conference about the effort, AFT President Randi Weingarten set forth a vision of children riding on union-built and union-driven electric buses, arriving safely at union-taught schools.

The key to strong partnerships like these is trust, and building trust takes time. It doesn’t happen overnight or after just one meeting. Local unions pursuing climate justice that do not already have existing relationships with community partners should begin to open up dialogue as soon as possible. And while forming a coalition in itself can lead to tangible gains, winning truly transformative changes requires transformative coalitions that involve radical power sharing and democracy, as is the case in bargaining-for-the-common-good campaigns.

Bargain for the Common Good

Bargaining for the common good is an innovative way of building community-labor alignments to jointly shape bargaining campaigns that advance the mutual interests of workers and communities alike. At their heart, these campaigns seek to confront structural inequalities—not simply to agree on a union contract. A bargaining-for-the-common-good approach starts with teachers unions, students, and local community groups working together to develop and articulate a set of demands that serve the interests of students, workers, and the communities where they live and work. Importantly, all stakeholders should have an equal voice in proposing and developing common good proposals.

Some possible demands could be emissions reduction targets, energy efficiency investments, solar panel installations, and the creation of resilience hubs at public universities, colleges, and preK–12 schools. Other demands include divestment of public pensions and endowments from fossil fuel companies and reinvestment of those funds into socially responsible investments, as the AFT has resolved to do nationally.61 Expansion of public transportation options, including the free provision of mass transit to students or employees, and monetary or other incentives for workers who walk, bike, or use public transportation to commute to and from school are also possible demands. Public school teachers can also fight for climate justice to become a core part of the public school curriculum, as the Chicago Teachers Union has been doing, and for green energy CTE programs to be available to all high school students.

Hitting on many of these demands, UTLA, in partnership with students and several community organizations, developed and successfully negotiated a memorandum of understanding (as part of its contract bargaining) titled “Healthy, Green Public Schools.”62 The memorandum, Arlene Inouye (then UTLA’s bargaining co-chair and secretary, now retired) told me, includes climate literacy curricula; a green jobs study; a green school plan, including conversion to union-made electric buses and union-installed renewable energy systems; and clean water, free from lead and other toxins. Reflecting on the process and proposals that came from it, Arlene said, “it’s been very important that we continue to grow the coalition and continue to expand our common good demands…. We’re finding different angles to keep pushing the envelope.”63

Hold Decision Makers Accountable

Without clearly defined targets and an enforcement mechanism, green school plans are simply promises that can be broken when economic or political structures shift. To ensure that educational institutions are following through on their goals, unions can demand the formation of joint labor-management-community committees on reducing GHG emissions.64 Such committees can be tasked with assessing the employer’s emissions profile and developing climate action plans to reduce GHG emissions and promote climate justice, including the creation of resilience hubs and career opportunities for local community members. Instead of relying on politicians who may be too fearful to establish enforceable targets or take bold action, workers and community partners can persuade or, if need be, force their employers to do so.

Along these lines, the Boston Teachers Union has begun discussions with the city’s school board and City Hall regarding Mayor Michelle Wu’s plan for a Green New Deal for Boston Public Schools. “Our main focus,” Betsy Drinan of the BTU told me, “is to get the union a seat at the table and involved in the planning for what the Green New Deal for Boston Public Schools is about, what it looks like, and to make sure that school communities have input into that planning.”65 The goal, she said, is to have regular monthly meetings. Local education unions around the country can take similar steps to spearhead the process of greening our nation’s schools now.

Coordinate Efforts Across Localities

The impact of local efforts can be amplified when undertaken in concert with other localities making similar demands. One way to help coordinate local efforts is to become involved with the national AFT climate and environmental justice caucus.† Just as climate justice committees create a space within local unions for members to work on climate justice issues, the national caucus provides a space within the national union for local union climate justice committee members to share information—including best practices, challenges, and wins—and to potentially coordinate their efforts across political jurisdictions, learning from each other’s efforts. The caucus also helps advance the work of the national AFT climate task force by offering creative ideas and solutions and organizing horizontally across locals.

The Labor Network for Sustainability (LNS) has also been convening a cross-union Educators Climate Action Network with AFT and National Education Association members participating. The network emerged after conversations by education union activists at both the Labor Notes Conference and the national AFT convention in the summer of 2022. The network of over 100 union educators from across the country convenes monthly and is open to all education union members interested in tackling climate change and promoting climate justice.‡

Conclusion

In my experience, most educators, students, and school employees fully understand and are very concerned about the threat of climate catastrophe. As David Hughes, a member of the AFT national climate task force, said, “We as teachers represent truth, and we have to act in accordance with the truth.... We have knowledge, we’re teaching knowledge, and we’re generating knowledge about a catastrophe that’s incredibly important for everyone. We’ve got to use whatever mechanism we can to implement the logical change that follows from that knowledge.”66

Together with students and community partners, education unions can fight for and win a just transition that addresses not only the climate crisis, but also the inequality crisis. As anchor institutions in their communities, with large swaths of public land, buildings, parking lots, and roof space, educational institutions are ideal sites for renewable energy generation and resilience hubs. The good jobs that are created in the process, with strong labor standards and local hiring provisions, will contribute to forging a just transition to a more sustainable and equitable future. And the expansion of CTE and the incorporation of climate justice curriculum into schools will equip future workers as well as citizens with the skills and knowledge needed for a green sustainable economy. As with all major societal change, it begins by organizing and building power, then exerting influence on decision makers to advance an agenda that promotes equity.

Many education unions are already beginning this work, starting at the local level and coordinating nationally, but the potential for transformative change has only just begun to be tapped. The Inflation Reduction Act has an unlimited pot of money for investing in green schools, but it is only possible if we initiate the efforts locally and take advantage of the federal incentives. Passage of Bowman and Markey’s Green New Deal for Public Schools legislation would further supercharge these investments. As Ayesha Qazi-Lampert from the CTU climate justice committee told me, “It’s at the national level. It’s originating from below, too. If it’s just one without the other, it may or may not succeed. But if you’ve got both ends of the spectrum pushing in, you got a lot better chance of succeeding.”67

Will your local union be the next to join the effort and help advance a Green New Deal for education from below?

Todd E. Vachon is an assistant professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers University, the director of the Labor Education Action Research Network, and the author of Clean Air and Good Jobs: U.S. Labor and the Struggle for Climate Justice. He is also an American Federation of Teachers New Jersey vice president for higher education.

*To learn more about the societal costs of rising inequality, see “Greater Equality: The Hidden Key to Better Health and Higher Scores” in the Spring 2011 issue of American Educator: go.aft.org/sck. (return to article)

†Get involved with the AFT’s national climate and environmental justice caucus through this form: go.aft.org/b6z. (return to article)

‡Learn more, including how to get involved, by contacting the LNS at labor4sustainability.org/contact-us. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. S. Gibbens, “Hurricane Sandy, Explained,” National Geographic, February 11, 2019, nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/hurricane-sandy.

2. E. Winter, “Yes, Rare Extreme Weather Events Are Happening More Frequently,” Verify, September 8, 2021, verifythis.com/article/news/verify/extreme-weather-verify/extreme-weather-events-100-year-floods-storms-wildfires-more-frequent-often/536-3352b5ca-3b72-4215-8421-194dd761f40a.

3. R. Frank, “Soaring Markets Helped the Richest 1% Gain $6.5 Trillion in Wealth Last Year, According to the Fed,” CNBC, April 1, 2022, cnbc.com/2022/04/01/richest-one-percent-gained-trillions-in-wealth-2021.html.

4. United Nations, “Causes and Effects of Climate Change,” un.org/en/climatechange/science/causes-effects-climate-change#:~:text=Fossil%20fuels%20%E2%80%93%20coal%2C%20oil%20and,they%20trap%20the%20sun's%20heat.

5. M. Wallace, A. Hyde, and T. Vachon, “States of Inequality: Politics, Labor, and Rising Income Inequality in the U.S. States Since 1950,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 78 (2022): 100677.

6. D. Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007).

7. R. Wilkinson and K. Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better (London: Allen Lane, 2009).

8. H. Ritchie and M. Roser, “CO2 Emissions,” Our World in Data, Global Change Data Lab, 2020, ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions; and E. Saez, “Striking It Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States (Updated with 2018 Estimates),” University of California, Berkeley, Department of Economics, February 2020, eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2018.pdf.

9. Saez, “Striking It Richer.”

10. T. Luhby, “The Top 26 Billionaires Own $1.4 Trillion—as Much as 3.8 Billion Other People,” CNN Business, January 21, 2019, cnn.com/2019/01/20/business/oxfam-billionaires-davos/index.html.

11. D. Fischer, “‘Dark Money’ Funds Climate Change Denial Effort,” Scientific American, December 23, 2013, scientificamerican.com/article/dark-money-funds-climate-change-denial-effort; and D. Michaels, “Mercenary Science: A Field Guide to Recognizing Scientific Disinformation,” American Educator 45, no. 4 (Winter 2021–22): 20–25, 40, aft.org/ae/winter2021-2022/michaels. For helping students spot denialism, see J. Cook, “Teaching About Our Climate Crisis: Combining Games and Critical Thinking to Fight Misinformation,” American Educator 45, no. 4 (Winter 2021–22): 12–19, 40, aft.org/ae/winter2021-2022/cook.

12. H. Ward-Glenton, “Billionaires Emit a Million Times More Greenhouse Gases Than the Average Person: Oxfam,” CNBC, November 8, 2022, cnbc.com/2022/11/08/billionaires-emit-a-million-times-more-greenhouse-gases-than-the-average-person-oxfam.html.

13. Oxfam International, “A Billionaire Emits a Million Times More Greenhouse Gases Than the Average Person,” November 7, 2022, oxfam.org/en/press-releases/billionaire-emits-million-times-more-greenhouse-gases-average-person#:~:text=The%20report%20finds%20that%20these,in%20the%20bottom%2090%20percent.

14. J. Riestenberg and M. Bottari, “Who Is Behind the National Right to Work Committee and Its Anti-Union Crusade?,” PR Watch, Center for Media and Democracy, June 3, 2014, prwatch.org/news/2014/06/12498/who-behind-national-right-work-committee-and-its-anti-union-crusade.

15. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members—2022,” press release, US Department of Labor, January 19, 2023, bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf.

16. S. Greenhouse, “‘Old-School Union Busting’: How US Corporations Are Quashing the New Wave of Organizing,” The Guardian, February 26, 2023, theguardian.com/us-news/2023/feb/26/amazon-trader-joes-starbucks-anti-union-measures.

17. For an example of environmental racism, see H. Washington, “Healing a Poisoned World,” AFT Health Care 1, no. 1 (Fall 2020): 16–21, 44, aft.org/hc/fall2020/washington.

18. C. Tessum et al., “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure,” PNAS 116, no. 13 (March 11, 2019): 6001–6, pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1818859116.

19. J. Goodman et al., “Heat and Learning,” National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 24639, November 2019, nber.org/papers/w24639.

20. M. Gallagher, “When Climate Change Forces Schools to Close: Fires, Storms and Heatwaves Have Already Kept 1 Million Students Out of Classrooms This Semester,” The74, September 16, 2021, the74million.org/article/when-climate-change-forces-schools-to-close-fires-storms-and-heatwaves-have-already-kept-1-million-students-out-of-classrooms-this-semester.

21. R. Miller and I. Hui, “Impact of Short School Closures (1–5 Days) on Overall Academic Performance of Schools in California,” Scientific Reports 12 (February 8, 2022): 2079, nature.com/articles/s41598-022-06050-9.

22. For more detail on educational impacts of extreme weather, see R. Chakrabarti, “The Impact of Superstorm Sandy on New York City School Closures and Attendance,” HuffPost, December 6, 2017, huffpost.com/entry/hurricane-sandy-school-days_b_2360754.

23. Pew Charitable Trusts, “Flooding Threatens Public Schools Across the Country: Infrastructure Analysis Evaluates County-Level Flood Risk,” August 1, 2017, pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2017/08/flooding-threatens-public-schools-across-the-country; and A. Gregg, “U.S. Flooding Losses Will Spike 26 Percent by 2050 Due to Climate Change, Researchers Say,” Washington Post, January 31, 2022, washingtonpost.com/business/2022/01/31/climate-change-flooding-united-states.

24. S. Williamson et al., “Climate Change Impacts on Maryland and the Cost of Inaction,” Center for Integrative Environmental Research, University of Maryland, August 2008, mde.maryland.gov/programs/Air/ClimateChange/Documents/www.mde.state.md.us/assets/document/Air/ClimateChange/Chapter3.pdf.

25. A. Smith, N. Lott, and T. Ross, “U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather & Climate Disasters 1980–2023,” National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2023.

26. L. Leopold, The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2007).

27. Merriam Webster, s.v. “Transition” and “Just,” 2022, merriam-webster.com/dictionary/transition and merriam-webster.com/dictionary/just.

28. T. Vachon and J. Brecher, “Are Union Members More or Less Likely to Be Environmentalists? Some Evidence from Two National Surveys,” Labor Studies Journal 41 (2016): 185–203.

29. American Federation of Teachers, “A Just Transition to a Peaceful and Sustainable Economy,” Resolution, 2017, aft.org/resolution/just-transition-peaceful-and-sustainable-economy.

30. American Federation of Teachers, “In Support of Green New Deal,” Resolution, 2020, aft.org/resolution/support-green-new-deal.

31. American Federation of Teachers, “Divest from Fossil Fuels and Reinvest in Workers and Communities,” Resolution, 2022, aft.org/resolution/divest-fossil-fuels-and-reinvest-workers-and-communities.

32. A. Drake Rodriguez, “A Green New Deal for K-12 Public Schools: Transforming Education,” Climate + Community Project, July 2021, climateandcommunity.org/gnd-for-k-12-public-schools.

33. M. Lieberman, “Half of Schools Have Urgent Cooling and Heating Concerns, Survey Shows,” Education Week, July 13, 2021, edweek.org/leadership/half-of-schools-have-urgent-cooling-and-heating-concerns-survey-shows/2021/07.

34. E. Kitzmiller and A. Rodriguez, “The Link Between Educational Inequality and Infrastructure,” Washington Post, August 6, 2021, washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/08/06/school-buildings-black-neighborhoods-are-health-hazards-bad-learning.

35. Aspen Institute, K12 Climate Action Plan (Washington, DC: 2021), thisisplaneted.org/img/K12-ClimateActionPlan-Complete-Screen.pdf.

36. J. Bryant, “How Many Colleges Are in the U.S.?,” BestColleges, March 22, 2023, bestcolleges.com/blog/how-many-colleges-in-us.

37. An initial project could be the installation of building-level metering to track energy use, emissions, water use, and more, in order to track progress toward meeting sustainability goals.

38. For example, generating renewable energy locally will reduce the demand for dirty “peaker” power plants that fire up during peak energy usage hours and spew particulate matter pollution into communities causing increased rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases.

39. Learn more about the proposed Green New Deal for Education plan here: gndforpublicschools.com.

40. To learn more about the IRA and how it relates to schools, see N. Akopian, M. Faggert, and L. Schifter, K12 Education and Climate Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (Washington, DC: Aspen Institute, 2022), thisisplaneted.org/img/K12-InflationReductionAct-Final-Screen.pdf.

41. “Energy communities” are areas that are or have historically been heavily dependent on the extraction, processing, and/or concentrated use of fossil fuels; see Interagency Working Group on Coal & Power Plant Communities & Economic Revitalization, “Priority Energy Communities,” US Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory, energycommunities.gov/priority-energy-communities, and Interagency Working Group on Coal & Power Plant Communities & Economic Revitalization, “Energy Community Tax Credit Bonus,” US Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory, energycommunities.gov/energy-community-tax-credit-bonus.

42. Interagency Working Group on Coal & Power Plant Communities & Economic Revitalization, “Energy Community Tax Credit Bonus.”

43. M. Wines, P. McGeehan, and J. Schwartz, “Schools Nationwide Still Grapple with Lead in Water,” New York Times, March 26, 2016, nytimes.com/2016/03/27/us/schools-nationwide-still-grapple-with-lead-in-water.html.

44. For more on microgrids, see National Renewable Energy Laboratory, “Microgrids,” US Department of Energy, Alliance for Sustainable Energy, nrel.gov/grid/microgrids.html. For net-metering, see Solar Energy Industries Association, “Net Metering,” seia.org/initiatives/net-metering.

45. Aspen Institute, K12 Climate Action Plan.

46. Betsy Drinan, personal communication with T. Vachon, February 7, 2023.

47. Chicago Teachers Union Foundation, “Climate Justice Education Project,” ctuf.org/climate-justice.

48. Ayesha Qazi-Lampert, personal communication to T. Vachon, February 7, 2023.

49. Qazi-Lampert, personal communication to Vachon, February 7, 2023.

50. A. Karp, “Educating for Climate Activism, Autonomy and System Change,” in Encyclopedia of Educational Innovation, ed. M. Peters and R. Heraud (Singapore: Springer, 2022), freedomsurvival.org/educating-for-climate-activism-autonomy-and-system-change.

51. M. Brix, “Peoria’s CTE Renaissance,” American Educator 46, no. 3 (Fall 2022): 6–11, aft.org/ae/fall2022/brix.

52. T. Vachon, Clean Air and Good Jobs: U.S. Labor and the Struggle for Climate Justice (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023).

53. James Boyle, personal communication to T. Vachon, September 20, 2019.

54. Alexa Harris, personal communication to T. Vachon, November 7, 2022.

55. J. Rosen and J. Brown, “Rutgers-Camden Faculty Oppose the Plan to Haul Liquified Fracked Gas Across South Jersey,” NJ.com, June 21, 2022, nj.com/opinion/2022/06/rutgers-camden-faculty-oppose-the-plan-to-haul-liquified-fracked-gas-across-south-jersey-opinion.html.

56. P. Le, “Ref. 52 Would Issue Bonds to Pay for School Energy,” Seattle Times, October 8, 2010, seattletimes.com/seattle-news/ref-52-would-issue-bonds-to-pay-for-school-energy.

57. Climate Jobs Illinois, “Carbon Free Healthy Schools,” climatejobsillinois.org/schools.

58. A. Licitra, “AFT, UAW Call for Union-Built Electric School Buses,” American Federation of Teachers, June 2, 2022, aft.org/news/aft-uaw-call-union-built-electric-school-buses.

59. J. Doerr, “The Ubiquitous Yellow School Bus Can Be Turned into a Force for Climate Change Good,” Time, January 12, 2022, time.com/6138439/american-school-bus-electric-climate-change.

60. P. Monahan, Clean School Bus Pollution Report Card 2006: Grading the States (Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists, 2006), ucsusa.org/resources/clean-school-bus-pollution-report-card.

61. American Federation of Teachers, “Divest from Fossil Fuels.”

62. The entire platform is summarized here: United Teachers Los Angeles, “The Beyond Recovery Program,” utla.net/app/uploads/2022/07/Beyond-Recovery-Platform_Full.pdf.

63. Arlene Inouye, personal communication with T. Vachon.

64. Rutgers AAUP-AFT made such a demand during postdoc negotiations in 2018, and although not won in bargaining, it did win the creation of such a committee in 2022 following a number of protest actions.

65. Drinan, personal communication with Vachon, February 7, 2023.

66. David Hughes, personal communication with T. Vachon, July 18, 2020.

67. Qazi-Lampert, personal communication with Vachon, February 7, 2023.

[Illustrations by Isabel Espanol]