Among the many tensions that the year 2020 laid bare, the divisions in our beliefs about the continued role of racism in the United States were central. While some of these divisions were drawn along political lines, with liberals far more likely than conservatives to see systemic racism as an ongoing problem, many were also drawn along racial lines. Although Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s and Breonna Taylor’s deaths brought together one of the largest multiracial coalitions in recent protest history,1 our nation remains divided in beliefs about the root causes of racial injustice, what we should do about it, and who is willing to do the work.2

According to several national polls, white Americans are more likely to deny that racism is a problem in contemporary US society than people from many communities of color.3 Even in the wake of increased televised and social media conversations about systemic racism, white Americans were less likely to take actions to better understand the racial issues plaguing American society, or to indicate support for Black Lives Matter, than people in other racial groups.4 In my home state of North Carolina, polling indicated that while 87 percent of Black Americans thought systemic racism was a serious issue, only 40 percent of white Americans agreed with this sentiment.5

In the face of persistent disparities that impact Black Americans’ experiences and outcomes regarding education, health, income, wealth, and criminal justice,6 these gaps in our perceptions about what constitutes racism and whether it is a persistent problem only widen another gap: what we need to do to address these disparities. As an educator, I’m interested in how we might bridge these perception gaps in the classroom. As a researcher, I also have some ideas about where to start. I am a social, cultural, and critical race psychologist who draws upon a diverse set of research tools—including experiments, quantitative analyses, and qualitative field research—to integrate scientific inquiry with applications to racial justice.

Our Stories Shape Our Perceptions

To begin, take a moment to think about what you would say if I asked you to tell me your life story, your personal history. What if you had limited time or only 500 words? What aspects of your life story would you think are most important to highlight? Would your highlights (or lowlights) differ if I were to ask you to tell your story to your students or to your colleagues? What kind of impact would you want your story to make, and would that change which details you included or excluded? Honestly, how much would you focus on the parts that make you feel good and those that make you feel bad?

I have been considering these types of questions in relation to our nation’s history since I started graduate school 15 years ago at the University of Kansas. Social-psychological research suggests that many of us are motivated to maintain a positive view of ourselves when recounting our pasts.7 I wondered: What does that emphasis on the positive mean for how we think about our country and, in particular, our history of racism? My master’s thesis and dissertation both focused on the dynamic relationships between identity, knowledge of America’s racial history, and beliefs about what constitutes racism. In my work, I consider both how our identities impact what aspects of our nation’s history we include in the collective narrative (especially what we commemorate) and what impact these narratives can make on engaged students.

In 1965, James Baldwin, a scholar and civil rights activist, implored white Americans to come to terms with the oppressive and bloody history of our nation’s past and asserted that doing so would be necessary to resolve the emotional and historical baggage perpetuating ongoing racism and discrimination. In an Ebony magazine article, he wrote:

White man, hear me! History, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations.8

History—or perhaps more accurately the stories we collectively tell ourselves about the past—shapes how we see the world, who we believe we are, and who we hope to be. At the same time, how we see the world, who we believe we are, and who we hope to be all play important roles in our interpretations and attitudes about what is significant about the past. What happened in the past and its relevance for the present can be ambiguous, and this ambiguity provides space for psychological meaning-making, intervention, and action. My research leverages this ambiguity to empower educators committed to addressing racism in their classrooms. I’ve found that as students’ knowledge of America’s racial history deepens, so does their interest in addressing persistent inequities. But we have a long road ahead.

Representations of American history tend to sanitize or silence the more negative or racist elements in order to maintain a positive view of our country’s past and present.9 Our textbooks, curricula, and government-sanctioned holidays are no exception. These sources of historical information are not neutral accounts of what factually happened in the past; they are vulnerable to biases carried forward from the past and biases cultivated in the present.10 Take the enslavement of Black people, for example. In its comprehensive report on “teaching hard history,” the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) indicated that American slavery is often divorced from its brutal context:

Taken as a whole, the documents we examined—both formal standards and supporting documents called frameworks—mostly fail to lay out meaningful requirements for learning about slavery, the lives of the millions of enslaved people or how their labor was essential to the American economy for more than a century of our history. In a word, the standards are timid…. The various standards tend to cover the “good parts” of the story of slavery—the abolitionist movement being foremost here—rather than the everyday experiences of slavery, its extent and its relationship to the persistent ideology of white supremacy.11

In addition to reviewing state standards, the SPLC examined popular textbooks, interviewed teachers, and tested students’ knowledge of slavery. Every source pointed to the conclusion that our country is struggling to effectively address the topic of slavery. This is an urgent problem because, as the SPLC noted, “The persistent and wide socioeconomic and legal disparities that African Americans face today and the backlash that seems to follow every African American advancement trace their roots to slavery and its aftermath. If we are to understand the world today, we must understand slavery’s history and continuing impact.”12

When it comes to historical narratives in our racial history that include enslavement, rape, segregation, lynching, political assassinations, and other forms of terroristic violence, unsanitized examinations reveal a deep and disturbing past that is not in accord with the cherished view of America as a land of liberty and opportunity. Honest discussions can raise a tension between wanting to distance ourselves from ugly truths and needing to reckon with them so that we might understand their relevance and manifestations in the present. In my own work, I’ve seen how this tension arises within celebrations of Black History Month, a time often dedicated to celebration, but also a time in which the relevance of these conversations is central.

Historical Knowledge Can Facilitate Perceptions of Systemic Racism

When I entered my psychology graduate program, I was primarily interested in racial identity and how that was related to perceptions of racism. However, several faculty members, including my advisor, were also discussing the implications of history knowledge as an important psychological variable for various perceptions;13 I was immediately drawn in. We were conducting several initial studies (including my master’s thesis14) measuring the relationship between Black history knowledge and perceptions of racism when I wondered about the cultural sources of Black history knowledge. I wondered what type of Black history content might be present (or absent) in different schools. I thought Black History Month might be a particularly good time to ask this question.

During Black History Month, schools vary in what events or people they think are best to highlight. While some schools may take their cues from larger districtwide initiatives or turn to historical societies (like the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) for ideas, the representations of Black history that wind up in the library or school display cases are also contingent on who volunteers to lead the efforts (students, teachers, or staff) and who is perceived to be the audience of such content.

During graduate school, I began conducting a series of studies15 to explore how Black History Month was commemorated in local high schools. The first, an ethnographic field study16 in 12 high schools, revealed that Black History Month commemorations differed according to the student population. In the seven schools where most (84 to 92 percent) of the students were white, the more negative and painful aspects of Black history were less likely to be included than in the five schools where most (72 to 98 percent) of the students were Black and Latinx.

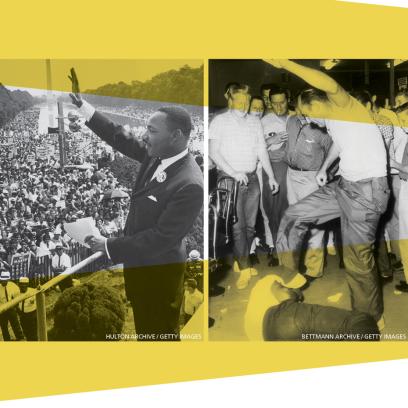

Generally, most Black History Month commemorations used two sanitizing strategies to silence negative histories. One strategy was to highlight individual Black American achievement—whether inventors, intellectuals, or civil rights heroes—while minimizing the historical barriers that these individuals faced or the collective struggle involved in order to eliminate those barriers. For example, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech would be highlighted, and he would be celebrated as a civil rights hero, but the violent context that necessitated King’s speech, as well as the organizing and demonstrations of the civil rights movement, would not be mentioned. The other strategy directed discussions about Black history toward multicultural tolerance and diversity instead of discussing race or history at all. The ongoing legacy of systemic expropriation, exploitation, and oppression was not brought to the table because of concerns that these conversations could make students feel bad. Instead, messages like “diversity is the one true thing we all have in common” appeared to be designed to make students feel good.

Although these sanitizing strategies were evident in all 12 schools, they were used far more extensively in the predominantly white schools. When students of color were in the majority, Black History Month commemoration materials were more likely to acknowledge historical racism, institutional barriers, and current impacts of longstanding oppression.

In a follow-up study,17 I asked college students to engage with high schools’ Black History Month materials. The college students saw materials from schools that enrolled mostly Black and Latinx students and mostly white students, but where the materials came from was kept hidden. Notably, white college students preferred the content from the predominantly white schools (which was more likely to be celebratory and diversity focused without explicitly presenting narratives about historical racism) over the materials from predominantly Black and Latinx schools (which were more likely to acknowledge historical racism).

After this preference emerged, my research team and I wanted to know whether these varying representations of history impacted perceptions of racism today. We conducted a third study18 in which participants were randomly assigned to engage with one of the three sets of facts (which I created based on the high school materials): celebratory representations of Black history that emphasized past achievements of Black Americans, critical representations of Black history that emphasized historical instances of racism, and (as a control condition) representations of US history that excluded people of color. Then, they were asked to indicate (1) whether various ambiguously racist events were due to racism and (2) their support for anti-racism policies.

A key finding from this work is that participants exposed to critical representations of Black history not only perceived greater racism in US society but also indicated greater support for policies designed to address racial inequality than did participants in the other two conditions. Sanitized representations that minimized racism in the past undermined perceptions of racism in the present and, in turn, resulted in less support for anti-racism policies. Think about that for a moment: accurate historical knowledge increased perception of racism in the present and also facilitated support for anti-racism policies. Historical knowledge can be a directive force, influencing how we comprehend current events and proposed responses (e.g., reparative action, apologies, or compensation).

Further support for the power of accurate Black history knowledge has emerged from my research collaborations examining the Marley hypothesis.19 The Marley hypothesis generally proposes that the perception (rather than denial) of racism in US society reflects accurate knowledge about historically documented instances of past racism. The name comes from Bob Marley’s song “Buffalo Soldier,” which reminds us of essential historical truths: “There was a Buffalo Soldier, In the heart of America, Stolen from Africa, … fighting for survival, … If you know your history, Then you would know where you coming from, Then you wouldn’t have to ask me, Who the heck do I think I am.”

In the original study20 and the replication,21 Black American college students were more accurate about historically documented racism than white American college students. For example, Black students were more likely to know that the Emancipation Proclamation did not abolish slavery throughout the United States and that full citizenship was not established for Black Americans until the 14th Amendment. As evidence of the Marley hypothesis, differences in historical knowledge facilitated differences in perceptions of racism in contemporary events among the Black and white students. In other words, the racial gap in perceptions about racism today—much like the gaps in perceptions evident in the national polls described in the introduction—was in part explained by racial differences in historical knowledge.

The implication of this work is that Black Americans’ tendencies to perceive racism are not forms of strategic exaggeration (i.e., “playing the race card”), but instead constitute realistic concerns about enduring manifestations of racism that are grounded in accurate knowledge about America’s racial history. In our studies, denial of racism was associated with ignorance about historically documented facts in our country’s racial history.

Classroom Interventions to Increase Recognition of Systemic Racism

This line of research suggested some fairly straightforward, fruitful directions for interventions in the classroom. If we want to bridge the gap between perception and denial of systemic racism, then we could teach critical histories. In a study22 led by my collaborator Courtney Bonam of the University of California, Santa Cruz, we recruited a sample of white Americans to listen to a clip of historian Richard Rothstein on NPR’s Fresh Air program discussing the federal government’s role in creating Black ghettos and the ongoing legacy of systemic racism in housing.23 Participants learned about redlining, blockbusting, and other discriminatory housing practices. (If you would like to learn more about this history, see an excerpt from Rothstein’s 2017 book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.) We found that listening to the NPR clip increased critical history knowledge (in comparison to a control condition), increased beliefs about the government’s active role in creating Black ghettos, and, in turn, increased perceptions of systemic racism.

However, though effective overall, participants’ identities interacted with the effectiveness of the intervention. In the original Marley hypothesis study,24 the more positively Black Americans regarded their racial identity, the more likely they were to perceive racism in American society. In contrast, the more positively white Americans regarded their racial identity, the less racism they saw in contemporary events. In the context of our intervention, the tensions between white racial identity and perceptions of racism were notable. As white racial identity increased, engagement with our critical history lesson (the NPR clip) became less likely to increase systemic racism perceptions. The data suggest that critical historical knowledge is important, but the effectiveness of teaching critical history may depend on how open our students are to information that can be threatening to their identities and what we can do to mitigate that threat.25 The study results are also consistent with my own personal experience in the classroom.

Bridging the Divide in My Own Classroom

[caption align="right"] [/caption]

Over the last 10 years, I have primarily taught courses in higher education that count toward diversity requirements for bachelor’s degrees, diversity requirements for psychology majors in particular, or courses that meet other general requirements related to racial equity or justice. In the past, sometimes those classes were large, hosting around 100 students, and other times they were intimate, small-class settings with only 10 to 12 students. Regardless of the size, there were always some students who self-selected into my courses because of genuine interest, while others openly admitted that they were just looking to check off another course from their list of required classes.

I am committed to teaching these courses because critical diversity content is intimately tied to my research expertise and my training as a cultural and critical race psychologist. I think it is important to tie in critical historical content across subject areas, even in domains where students may not believe the connections are relevant (at least initially). This is not always an easy approach, but it is a key one if you are committed to helping your students understand racism as a historical, cultural, and structural construct.

I accepted early on that one of the consequences of teaching critical diversity content is that it can be emotionally challenging for students.26 Highlighting the kind of issues instructors can encounter, Alexander Kafka of the Chronicle of Higher Education discusses the disproportionate amount of emotional labor spent by instructors in diversity courses.27 Kafka reviews research presented at the Association for the Study of Higher Education’s annual conference by Drs. Ryan Miller, Cathy Howell, and Laura Struve in which they defined emotional labor as “attending to students’ needs beyond course content, both inside and out of the classroom, as well as addressing one’s own emotional management and displays as a faculty member.”28 Of course, any class could require some additional attention to students’ needs and requests outside of the classroom, but as Howell, who is a Black woman, revealed, a significant portion of her own emotional labor included “being the depository of anger and frustration experienced by students.”29 As a regular instructor for these types of courses, I have experienced being such a depository personally (often through eye-rolling and outbursts in class) and grappled with it on teaching evaluations. I know those written-in comments can really shine or rain on your parade.

A few years ago, as I was preparing to deliver a lecture on “Racism and Oppression” in my Psychology of Culture and Diversity course, I realized that I had come to anticipate some level of anger and frustration among some of my students—so much so that it had impacted some of my teaching practices. After some critical reflection, I knew I was managing their reactions to both the message and the messenger. I learned that it was important to cover what is typically experienced as the most uncomfortable content after I’ve had some time to earn their trust. At the very beginning of the semester, many students express their excitement for learning more about psychology in “other” cultures. They do not necessarily anticipate the critical, challenging lessons about racism that lie ahead.

My courses challenge students to understand themselves as cultural beings with “different” cultural patterns too. Culture and diversity are not just about “others” and their psychological experiences; everyone’s psychological experiences are intimately tied to cultural processes as consumers and producers. My lectures on racism and oppression build on this idea by asserting that racism is systemic and embedded in our cultural context. In psychology textbooks, systemic racism is not a term often used; most of my students are not used to thinking about racism this way. One way I manage this is by packing the lecture with interactive and experiential activities30 that aim to help them process a sociocultural understanding of racism; this larger concept of racism may be more threatening than the typical portrayal of racism as individual bias.31

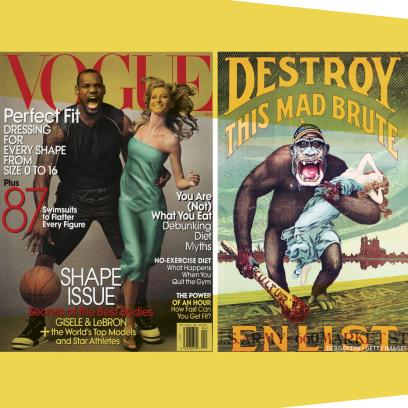

Another approach I use includes arriving to class early to play Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier” before introducing my students to the Marley hypothesis. We discuss explicit and ambiguous examples of racism and their connections to the past. One particularly vivid example includes discussion of a 2008 Vogue cover of LeBron James and Gisele Bündchen. When the image is presented on its own, many students suggest that claims of racism are wildly exaggerated. When paired with a World War I recruitment poster from 1917 with a gorilla abducting a fragile white woman (a la King Kong) with the central message “Destroy This Mad Brute,” the juxtaposition of the two images suggests that James and Bündchen were styled to mirror racial stereotypes about Black men as dangerous. I ask them to consider Emmett Till and how false accusations of him inappropriately interacting with a white woman precipitated his lynching. Then, I ask the students to consider how their knowledge of the historical poster has shaped their perceptions of racism when reexamining the Vogue cover. Suddenly, claims of racism are not deemed so wildly exaggerated.

Throughout my courses, we look backward and forward. When we discuss historical instances of racism, we also discuss their implications for the present. For example, many psychology students will read about the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment as a lesson on research ethics, but it’s also important to discuss the legacy of historical racism to gain new perspective on who feels comfortable participating in medical trials and who has access to quality medical care.

Despite the challenges, my research and teaching experiences have only strengthened my belief that, as teachers, we can have a positive impact on our students’ and our society’s responses to systemic racism. In many ways, it is striking that brief interventions in laboratory settings can shift our awareness and perceptions of systemic racism. Recognizing systemic racism is only a first step; dismantling racism will require collective action with support from robust anti-discrimination laws and anti-racist policies. But, recognition is a crucial step, nonetheless. I hope, with future work, that we can better understand the social conditions that facilitate acceptance of the difficult truths in our racial history and commitments to social action. The classroom is a great place to start deepening society’s understanding of racism past and present, and our willingness to do something about it.

Phia S. Salter is an associate professor of psychology at Davidson College and the principal investigator of the Culture in Mind Research Collaboratory, where her research focuses on collective memory, social identity, and systemic racism. Previously, she was an associate professor of psychology and Africana studies at Texas A&M University.

Endnotes

1. L. Buchanan, Q. Bui, and J. K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History,” New York Times, July 3, 2020.

2. F. Newport, “Seeking Solutions for Racial Inequities,” Gallup, September 11, 2020.

3. See, for example, UMass Lowell Center for Public Opinion, “American Opinions on Race, Policing, Systemic Racism,” August 20–25, 2020; CNN, study conducted by SSRS, August 28–September 1, 2020, cdn.cnn.com/cnn/2020/images/09/04/rel9b.-.race.pdf?utm_source=link_newsv9&utm_campaign=item_320096&utm_medium=copy; and M. Brenan, “Optimism About Black Americans’ Opportunities in U.S. Falls,” Gallup, September 16, 2020.

4. A. Florido and M. Peñaloza, “As Nation Reckons with Race, Poll Finds White Americans Least Engaged,” NPR, August 27, 2020.

5. M. Burns, “Poll: Nearly Quarter in NC Don’t View Systemic Racism as a Problem,” WRAL, October 16, 2020.

6. See, for example, S. Roberts and M. Rizzo, “The Psychology of American Racism,” American Psychologist, June 25, 2020, advance online publication; and D. Francis and C. E. Weller, “The Black-White Wealth Gap Will Widen Educational Disparities During the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Center for American Progress, August 12, 2020.

7. A. Wilson and M. Ross, “The Identity Function of Autobiographical Memory: Time Is on Our Side,” Memory 11, no. 2 (2003): 137–149; and D. P. McAdams and K. C. McLean, “Narrative Identity,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 22, no. 3 (2013): 233–238.

8. J. Baldwin, “The White Man’s Guilt,” Ebony, August 1965, 47.

9. J. W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (New York: Touchstone, 1996); and Richard Rothstein, “Historian Says Don’t ‘Sanitize’ How Our Government Created Ghettos,” interview by Terry Gross, “Fresh Air,” NPR, May 14, 2015.

10. A. Wong, “How History Classes Helped Create a ‘Post-Truth’ America,” The Atlantic, August 2, 2018.

11. K. Shuster, Teaching Hard History: American Slavery (Southern Poverty Law Center, January 31, 2018), 29.

12. Shuster, Teaching Hard History, 9.

13. J. C. Nelson et al., “The Role of Historical Knowledge in Perception of Race-Based Conspiracies,” Race and Social Problems 2, no. 2 (2010): 69–80; and B. Doosje et al., “Guilty by Association: When One’s Group Has a Negative History,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75, no. 4 (1998): 872.

14. P. S. Salter, “Perception of Racism in Ambiguous Events: A Cultural Psychology Analysis” (master’s thesis, University of Kansas, 2008).

15. P. S. Salter and G. Adams, “On the Intentionality of Cultural Products: Representations of Black History as Psychological Affordances,” Frontiers in Psychology 7 (2016); P. S. Salter, G. Adams, and M. J. Perez, “Racism in the Structure of Everyday Worlds: A Cultural-Psychological Perspective,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 27, no. 3 (2018): 150–155; P. S. Salter and G. Adams, “Provisional Strategies for Decolonizing Consciousness,” in Antiracism Inc.: Why the Way We Talk About Racial Justice Matters, ed. F. Blake, P. Ioanide, and A. Reed (Santa Barbara, CA: Punctum Books, 2019), 299–323; and G. Adams and P. S. Salter, “They (Color) Blinded Me with Science: Counteracting Coloniality of Knowledge in Hegemonic Psychology,” in Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness Across the Disciplines, ed. K. Crenshaw et al. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019), 271–292.

16. Salter and Adams, “On the Intentionality,” 1166.

17. Salter and Adams, “On the Intentionality.”

18. Salter and Adams, “On the Intentionality.”

19. J. Nelson, G. Adams, and P. Salter, “The Marley Hypothesis: Denial of Racism Reflects Ignorance of History,” Psychological Science 24, no. 2 (2013): 213–218; and C. Bonam et al., “Ignoring History, Denying Racism: Mounting Evidence for the Marley Hypothesis and Epistemologies of Ignorance,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 10, no. 2 (2019): 257–265.

20. Nelson, Adams, and Salter, “The Marley Hypothesis.”

21. Bonam et al., “Ignoring History.”

22. Bonam et al., “Ignoring History.”

23. Rothstein, “Historian Says Don’t ‘Sanitize.’ ”

24. Nelson, Adams, and Salter, “The Marley Hypothesis.”

25. See also A. Haugen et al., “Theorizing the Relationship Between Identity and Diversity Engagement: Openness Through Identity Mismatch,” in Venture into Cross-Cultural Psychology: Proceedings from the 23rd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, ed. M. Karasawa et al. (2018).

26. C. Kernahan and T. Davis, “Changing Perspective: How Learning About Racism Influences Student Awareness and Emotion,” Teaching of Psychology 37, no. 1 (2007): 49–52.

27. A. Kafka, “Instructors Spend ‘Emotional Labor’ in Diversity Courses, and Deserve Credit for It,” Chronicle of Higher Education, November 15, 2018.

28. Kafka, “Instructors Spend.”

29. Kafka, “Instructors Spend.”

30. T. Kurtis, P. Salter, and G. Adams, “A Sociocultural Approach to Teaching About Racism,” Race and Pedagogy Journal 1, no. 1 (2015); and B. Morling and D. Myers, “Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science,” Association for Psychological Science, March 30, 2018, psychologicalscience.org/observer/teaching-current-directions-in-psychological-science-47#racism.

31. G. Adams et al., “Teaching About Racism: Pernicious Implications of the Standard Portrayal,” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 30, no. 4 (2008): 349–361.