The high school’s information technology (IT) specialist looked at me with a mixture of amusement and bewilderment. He had become the person in charge of managing IT at a local high school that had recently decided to implement a one-to-one tablet program.

His most recent task was to refurbish the 1,500 or so tablets that had been turned in after the first year. As anyone working with high school students can attest, there is normally significant wear and tear on any item after a full year’s use.

“What was the most surprising thing you found when you went through all the tablets?” I asked, expecting that most of the time was spent fixing broken screens and replacing missing covers.

“Well,” he said slowly, “one thing that surprised me was that some of the students, and I went back and figured out they were mostly freshman boys, had tablet screens completely covered with documents. It was as if they just saved everything to the home screen of their tablet for the entire year.”

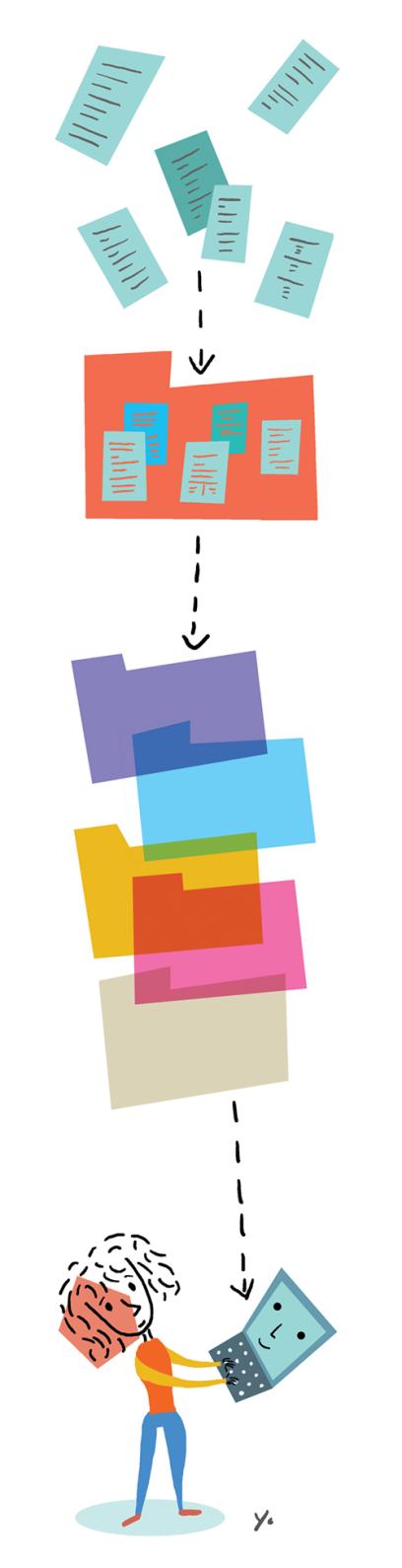

In other words, these students had never learned or appreciated the simple genius of digital folders.

He went on to describe the overall physical condition of these tablets—they were also, unsurprisingly, somewhat of a mess. It didn’t take long for me to realize the scope of this newfound problem: for years, I dealt with students’ crumpled papers, usually discovered at the bottom of backpacks or spilling out of binders. Now, those crumpled papers were digital, quietly hidden within the confines of a sleek tablet that itself might be stuffed at the bottom of a backpack.

The lack of physical signs of disorganization was one reason many teachers and administrators were unaware of the root cause of the problem.

Over time, I realized that although they went to great lengths to make sure students knew how to use programs to help with note taking and information retention, such as Notability and Microsoft OneNote, they had done nothing to help students come up with strategies for organizing files and managing workflow. They may have assumed students would figure these things out on their own, and in some cases, students did. In many cases, though, students did not—and often, they didn’t understand exactly why they felt so overwhelmed.

The school also had not provided clear guidelines for faculty on how and where to announce assignments and exams, and how to distribute and collect assignments and essays. As a result, students were juggling standards and expectations from six or seven different teachers. Some teachers preferred Google Docs, others used Dropbox or Box to manage file sharing, and still others used apps that are now unavailable. The new standards around tablet use created an entirely new language, but in many cases, students were left without a dictionary.

The New Language of Technology in Schools

Just as social media created a new language that causes a rift in understanding between many adults and adolescents, so too has the use of technology in classrooms. As an educational consultant, I spend much of my time helping young people harness the power of technology to improve their organization and time-management skills. In my book Social Media Wellness: Helping Tweens and Teens Thrive in an Unbalanced Digital World, from which this article is drawn, I write about the time I presented an in-service workshop to middle school teachers and administrators. The teachers were incredibly engaged and forthcoming, and they truly believed technology had made their lives—as well as the lives of their students—much easier. I casually asked one teacher about how he communicates homework to students and how students were asked to turn in their assignments. As he shared his method, another teacher from the other side of the room blurted out, “Wow—I do it completely differently!” Within each department, many teachers had similar strategies for managing workflow, but across the school, there was no consistent strategy for sharing information or for distributing and collecting assignments.

I then shared results from a survey given to their students just a few weeks prior. Over half the students said it took them at least 30 minutes every day to figure out their assignments. After the school instituted an online learning management system, many teachers no longer announced assignments in class, believing they were saving valuable time by telling students to check the school’s online portal. In reality, students would attempt to navigate said portal from home and were at times faced with spotty Wi-Fi connections, glitches with the portal, or homework assignments that hadn’t been updated. Even when things went smoothly, students were easily distracted from recording homework simply by being online. At the same time, some teachers used the online portal diligently, whereas others would forget to post altogether but figured that mentioning an assignment out loud at the end of class was sufficient.

This school, like many of the schools I visit that have adopted tablet or computer programs, also stopped giving students written planners. Eliminating written planners provided a substantial cost savings, but administrators hadn’t tried using online task or homework management options. If they had, they might have realized that many of the online options don’t help students who want to plan out their entire week in advance (including appointments, extracurricular activities, sports practices, and family obligations).

My students repeatedly told me how much they benefited from keeping their tasks and schedule all in one place. Writing everything down offline encouraged compartmentalization and allowed them to identify tasks that needed to be focused on individually. When students go online to figure out a homework assignment, they are inevitably tempted by the internet’s endless possibilities. Using a written planner helps to prevent that temptation.

Below, I highlight for teachers and students some specific organization and time-management strategies that have worked for many of the students I see in my office and at the schools I’ve consulted with in the past. I believe that organizing assignments and managing workflow are directly related to academic wellness, which centers on learning better ways to navigate our always-on world.

Virtual Folders and In-Real-Life Binders

When students came to see me 15 years ago, we would go through all their papers—every single one—and put them in binders, one for each subject, with five tabs:

1. “Notes,” for notes taken in class;

2. “Homework,” for assignments (those recently completed and ready to be turned in on the top, with returned work underneath);

3. “Handouts,” for any useful information a teacher might provide;

4. “Test/Quizzes,” for study guides and returned assessments; and

5. “Paper,” for extra loose-leaf paper.

Everything was hole-punched, and the front and back pockets of the binder were to remain empty. Within this framework, students adjusted as needed: my usual advice was that since it was their binder, they could figure out what would go where.

Today, things are a bit more complicated. Students at schools with one-to-one tablet or computer programs usually store the majority of their files on their computer or, more recently, in the cloud, using a file-sharing and content management system. Many students still have a few papers and need some sort of physical binder system, though one binder for each class seems somewhat excessive.

I encourage students to create a file folder on their tablet’s home screen or desktop for each of their classes and to create sub-folders within the individual class folders titled “Notes,” “Homework,” “Handouts,” and “Test/Quizzes.” Some students might want to break down those folders further by topics, chapters, or sections of information studied, but again, that is optional. Essentially, we take the physical system and transfer it into a digital one.

Teaching kids how to organize and file documents may seem mundane, but as someone who has seemingly filed over a million papers in my lifetime, I have witnessed the relief conveyed on the face of a child whose 892 pieces of loose-leaf paper now have a designated home. That same relief is apparent when I make students sit in my office and create digital file folders and file every digital document.

It’s not enough to simply have students create virtual folders and physical binders—there also needs to be time for a daily or weekly regrouping to help them stay organized. Nearly all students are well-meaning, starting out with the greatest intentions around organization, only to fall off track. Building in a daily or weekly regrouping can be done easily at home or in the classroom, and it can make a world of difference.

Mapping Out Assignments and Activities

Over the past decade, I’ve seen many schools with tablet and computer programs stop distributing paper planners—and then slowly realize their mistake. Many administrators reasoned that planners, which often end up lost, ripped, or unused, are a waste of paper and resources. They might not always be used or kept in ideal conditions, but there are a number of reasons why schools should rethink that decision—and why students should think about continuing to track assignments and activities with a written, visual planner, even if the school doesn’t provide one.

A written, visual planner enables students to keep all their assignments and activities in one place, ideally with ample room to record assignments, projects, and exams, as well as track activities, family events, and appointments. Students can easily number their assignments and prioritize, and they are potentially less distracted by the possibility of going online. In essence, written planners are a simple way to encourage monotasking and compartmentalization.

I encourage teachers to normalize the use of written planners by creating time and space for students to bring out their planners in class and write down their assignments. For teachers who believe there isn’t enough time to do so, I suggest thinking of the time as a preventive measure: three minutes spent daily prevents hours of dealing with missing assignments, school counselor inquiries for failing grades due to missing work, and parent conferences due to low performance.

I’m a fan of the following five-step process for managing tasks on a written planner—students can do this at home or in class as part of a regular homeroom or advisory activity:

- Write down all the upcoming assignments for each class, including homework that is not due the next day. Students sometimes have several days to complete assignments, so I recommend they always start them (and, if possible, complete them) on the night the work is assigned, rather than the night before the assignment is due.

- Add any tests, long-term projects, or essays by writing them at the top of the day they are due.

- Add in any sports activities, family events, doctor’s appointments, and social happenings.

- Schedule in blocks of time for homework.

- Number assignments in order of priority and check them off when completed.

Today’s students live in a world of mini-multitasking. Merely scheduling time to do work using a written planner, or hoping students pay attention in class, doesn’t do much when a student has seven different screens up and is being bombarded with different messages and notifications. Students who are listening to a lecture while managing two text conversations, checking social media, and seeing if the shoes they want are now on sale aren’t able to process any of those things properly, and the mini-multitasking results in decreased productivity and increased exhaustion.

My goal is for students, teachers, and parents to recognize how compartmentalizing can increase productivity and decrease stress. For many people, compartmentalization and monotasking are underdeveloped skills that need to be developed over time. At first, it can feel uncomfortable, in a skin-crawling kind of way. But, I’ve had students diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder tell me they use the same strategies learned as a teenager in my office at their full-time job years later. There are certainly long-term benefits to learning those techniques early.

Ana Homayoun is an educator, school consultant, and author of three books, most recently Social Media Wellness: Helping Tweens and Teens Thrive in an Unbalanced Digital World (Corwin, 2017), from which this article is excerpted with permission. Follow her on Twitter @anahomayoun.