It is almost universally recognized that how schools are organized and managed—the realm of school leadership—is crucial for the success of students and school performance.1 Moreover, school officials and reformers have long held that the key to successful school leadership is to make the core activities of teaching and learning the primary focus of those making the decisions and managing schools.2

Indeed, what is often called “instructional leadership” has been the equivalent of the Holy Grail in the management and administration of elementary and secondary schools.3 In this view, effective schools almost invariably emphasize key elements of instructional leadership, such as developing a shared purpose and vision among faculty and administrators in schools; fostering an atmosphere of trust, respect, and teamwork in the building; promoting high and consistent academic standards; providing objective, consistent, and useful assessment of the quality of teachers and teaching; using evidence and data to make decisions about the instructional program; and providing support for and recognition of teachers.4

Along with how closely schools focus on teaching and learning, a second concern often arises in relation to school leadership: who or which groups should have a role in the decision making in schools. A long-standing aspiration of many school reformers has been to see that teachers are granted an important role in the leadership and decision making within schools, especially beyond the classroom. In recent years, efforts to expand teachers’ roles in schools have increasingly come under the banner of “teacher leadership.”5 These new roles for teachers have taken a number of different forms and have used a variety of mechanisms. For instance, a growing number of states have enacted policies directing that public schools develop school-level leadership mechanisms, often called school improvement teams or school councils. The objective of these initiatives is to foster collective and shared decision making among key stakeholders in schools, specifically to include faculty. Often, such policies explicitly mandate that school teams and councils wield real authority over key decisions rather than simply serve in an advisory role.

A further development in teacher leadership and teacher professionalization is the small but growing number of “teacher-powered” schools*—schools that are collectively designed and led by teachers.6 Such schools are often explicitly modeled after the kind of partnerships that are common among white-collar vocations, such as lawyers, accountants, architects, auditors, and engineers, where the partners, as professionals, own, run, and are accountable for the success of the firm.

Given the prominence of both instructional leadership and teacher leadership in the realms of school reform and policy, not surprisingly, both have also been the focus of extensive empirical research. But there have been limits to this research. It is, for example, unclear which of the many key elements of instructional leadership are more, or less, likely to be adopted in schools across the nation. Similarly, it is unclear which of these elements are more, or less, beneficial for school performance and for student learning and growth.7 Likewise, though the extent of teacher involvement in school decision making has been widely studied, there has been almost no solid empirical research on whether teacher leadership is beneficial for student learning and growth.8 These topics are the subject of a study we undertook, which this article summarizes.9

Our Study

The source of data for our study is the Teaching, Empowering, Leading and Learning (TELL) Survey, a unique, large-scale survey administered by the New Teacher Center in Santa Cruz, California.10 The TELL Survey collects data from teachers on an unusually wide range of measures of teaching and organizational conditions in schools and also obtains school-level data on student academic achievement. We analyzed data from almost 900,000 teachers, in about 25,000 public schools in 16 states, collected from 2011 to 2015.

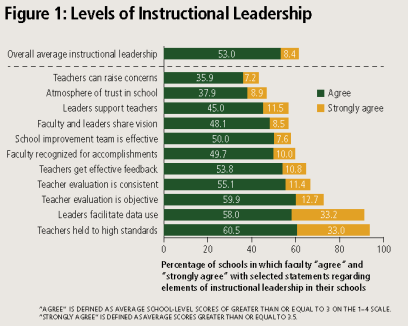

We focused on the TELL Survey’s set of questions on 11 key elements of effective instructional leadership, including whether teachers can raise concerns that are important to them, whether there is an atmosphere of trust in school, whether leaders support teachers, whether there is a shared vision for the school, whether there is an effective school improvement team, whether faculty are recognized for accomplishments, whether teachers get effective feedback, whether teacher evaluation is consistent, whether teacher evaluation is objective, whether school leadership facilitates data use to improve learning, and whether teachers are held to high standards. These questionnaire items used a four-point scale: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree.

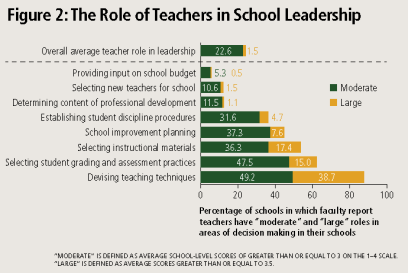

We also focused on the TELL Survey’s set of questions regarding the role of teachers in eight key areas of decision making and teacher leadership in schools: selecting instructional materials and resources, devising teaching techniques, setting grading and student assessment practices, determining the content of in-service professional development programs, establishing student discipline procedures, providing input on how the school budget will be spent, selecting and hiring new teachers, and school improvement planning. These questionnaire items used a four-point scale as well: none, small, moderate, and large.

Our student achievement measure was the school’s student proficiency ranking within its state as compared with all other schools in the state, in that year, for state tests in both mathematics and English language arts (ELA).

Findings on Instructional Leadership

We found that schools vary dramatically in which elements of instructional leadership they emphasize and implement. For example, in over 90 percent of the schools, the faculty “agree” or “strongly agree” that “teachers are held to high professional standards for delivering instruction.” On the other hand, in fewer than half of the schools did “teachers feel comfortable raising issues and concerns that are important to them” (see Figure 1 below).

In general, the data indicate that schools are more likely to implement those elements of instructional leadership that are aligned with enhancing high standards, teacher accountability, evaluation, and performance. In contrast, schools are less likely to emphasize those elements of instructional leadership that entail recognition of, and support for, teachers and that are aligned with enhancing teacher “voice” and input into decision making.

In addition, the data reveal dramatic differences in levels of instructional leadership across different types of schools. School poverty level was a key factor. In nine of the 11 elements of instructional leadership, faculty in high-poverty schools rated their school’s instructional leadership lower than did faculty in low-poverty schools. For instance, in less than half of the high-poverty schools, faculty reported that the school’s leadership consistently supports teachers; in contrast, this was true of about 60 percent of low-poverty schools. The gap was even larger regarding whether a school has an atmosphere of trust and mutual respect (38 percent for high-poverty schools, compared with 50 percent for low-poverty schools).

Not only do schools vary in the extent to which they implement key elements of instructional leadership, but the data show this is related to differences in how well their students perform on state achievement tests. We have found that instructional leadership is independently, significantly, and positively related to student achievement, after controlling for the background characteristics of schools (such as poverty level), and this is so for both mathematics and ELA.

Our statistical analyses show that schools with the highest levels of overall instructional leadership rank substantially higher in both mathematics and ELA in their state than schools with the lowest levels of overall instructional leadership. (For more details on these findings, see our full paper.)

What aspects of instructional leadership seem to matter most in terms of student achievement? Our statistical analyses show that some elements of instructional leadership have a stronger relationship with student achievement than others. Those elements are: (a) holding teachers to high instructional standards, (b) providing an effective school improvement team, and (c) fostering a shared vision for the school.

But the data also reveal that many schools lag in those elements. For instance, in only a minority of schools did faculty strongly agree that there is a shared vision (8.5 percent) or an effective school improvement team (7.6 percent), yet these elements have among the strongest ties to student achievement. On the other hand, many schools strongly emphasize elements of instructional leadership that have weaker relationships to student achievement, such as providing objective and consistent teacher performance evaluation.

Hence, we found an imbalance: schools often do not emphasize, and sometimes even neglect, elements of instructional leadership that are more strongly related to student achievement, while emphasizing elements that are less related to student achievement. In particular, schools are strikingly less likely to implement elements that enhance teacher authority and leadership, even though some of these have the strongest ties to student achievement. And conversely, schools are more likely to implement elements that enhance accountability and teacher evaluation, which have the weakest ties to student achievement.

Findings on Teacher Leadership

Our study also focused on teacher leadership—specifically, the role of faculty in key areas of decision making in their schools. As with instructional leadership, the data show large variations in teachers’ roles across different areas of decision making within schools. For example, in almost 90 percent of schools, teachers have either a “moderate” or a “large” role in “devising teaching techniques,” but they have such a role in less than 10 percent of schools when it comes to “providing input on how the school budget will be spent” (see Figure 2 below).

In general, we found that teachers more often have a substantial role in decisions regarding classroom academic instruction, teaching techniques, and student grading. They less often have a role in decisions that are schoolwide and beyond the classroom, both academic and nonacademic, such as establishing student behavior policies, engaging in school improvement planning, and determining the content of professional development programs.

Similar to the variations in instructional leadership, the data also reveal a wide range in the role of teachers in leadership across different types of schools. Again, school poverty level is one of the most prominent factors in these differences. For five of the eight areas of teacher leadership, faculty in low-poverty schools reported a larger role for faculty than in high-poverty schools. For instance, faculty have a substantial role in selecting new teachers in only about 9 percent of high-poverty schools; this was true for double that percentage in low-poverty schools.

Our analyses also show that teacher leadership is strongly related to student achievement. The results clearly show that teacher leadership and the amount of teacher influence in school decision making are independently and significantly related to student achievement, after controlling for the background characteristics of schools, and this is true for both mathematics and ELA.

For instance, schools with the highest levels of overall teacher leadership rank substantially higher in both mathematics and ELA in their state than schools with the lowest levels of overall teacher leadership. (For more details on these findings, see our full paper.)

What aspects of teacher leadership seem to matter most in terms of student achievement? Paralleling our findings for instructional leadership, some areas of teacher decision making are more strongly tied to student achievement.

Interestingly, the data suggest that faculty voice and control related to student behavioral and discipline decisions are more consequential for student academic achievement than teacher authority related to issues seemingly more directly tied to classroom instruction, such as selecting textbooks, choosing grading practices, and devising one’s classroom teaching techniques. School improvement planning is the decision-making area that has the next strongest association with student achievement.

While student achievement is clearly linked to teachers’ roles in both student discipline procedures and school improvement planning, it’s important to keep in mind that, in the majority of schools, teachers report having little role in either area (see Figure 2 above).

The finding on teachers’ role in school improvement planning is especially revealing when combined with the previously discussed instructional leadership data on school improvement teams. Collectively, these two sets of data—on instructional leadership and teacher leadership—indicate that having a school improvement team that provides effective leadership, and delegating a large role to teachers in school improvement planning, are among the most important practices associated with improved student achievement.

But the data also reveal that many schools do not have a school improvement team that provides effective leadership and, moreover, that most schools do not provide teachers a substantial role in such planning activities. This connection is important, as the data show that schools with more teacher involvement in school improvement planning are highly likely to also have a more effective school improvement team and better student achievement.

Once again, we find an imbalance: schools often do not promote some of the most consequential areas of teacher leadership, instead giving teachers a larger role in areas that appear to be less tied to student achievement.

In sum, we found that the degree of both instructional leadership and teacher leadership in schools is strongly related to the performance of schools. After controlling for school background demographic characteristics, schools with higher levels of instructional leadership and teacher leadership rank higher in student achievement, for both mathematics and ELA. Moreover, the data show that some elements of instructional leadership and teacher leadership are more strongly related than others to student achievement.

As mentioned, our analyses suggest the presence of an imbalance. Some of those elements of instructional leadership and teacher leadership that are most strongly related to student achievement are least often implemented in schools.

The data indicate that holding teachers to high instructional standards—a key element of instructional leadership that is conceptually aligned with enhanced accountability—is among the most strongly related to higher achievement. Two elements of instructional leadership that are conceptually aligned with enhanced teacher authority and leadership—providing an effective administrator-teacher school improvement team and fostering a shared vision among faculty and administration for the school—are also among the most strongly related to higher achievement. Yet, schools are far more likely to implement high teacher standards than they are to have effective school improvement teams or a shared vision.

We found similar results for teacher leadership: some areas of teacher leadership that are the most strongly related to achievement are least often present in schools. The data indicate that teachers’ roles in establishing student discipline procedures and school improvement planning are the most strongly related to student achievement. Yet, only a minority of schools give teachers a large role in either of these two key areas.

Our findings suggest the benefits of a balanced approach. In other words, schools that promote both teacher accountability and teacher leadership have better performance. In sum, our study suggests that leadership matters, that good school leadership actively involves teachers in decision making, and that these are tied to higher student achievement.

It is striking that teacher authority over student behavioral and discipline decisions appears more consequential for academic success than teacher authority over issues ostensibly more directly tied to classroom instruction. This raises the question: Why would teacher leadership in student discipline policies—a seemingly nonacademic area—so strongly relate to student academic success?

Earlier studies we have conducted analyzing other databases suggest an explanation.11 These analyses indicate that teachers are given primary responsibility for establishing classroom climate and managing student behavior. But they also show that teachers often have little input into decisions regarding schoolwide behavioral and disciplinary policies, norms, and standards for students. Instead, these rules and guidelines are largely conceived by others.

Similarly, teachers often have little say over the types of rewards or sanctions used to bolster or enforce these rules. These limitations on teachers’ authority can undermine their ability to take charge of their classrooms and successfully meet their responsibilities.

It is important to recognize, however, that teacher input into student behavioral policies is much more than simply a pragmatic issue of classroom management necessary for academic instruction to proceed. Schooling is not solely a matter of instructing children in the three Rs (reading, writing, and arithmetic) and passing on essential academic skills and knowledge. Schools are one of the major institutions for the socialization of our children. Teachers do not just teach academic subjects. They are also charged with furthering the social-emotional learning of their students.†

Poll after poll has shown that the public overwhelmingly feels one of the most important goals of schools is and should be to shape conduct, develop character, and impart values.‡ In this view, the relationships that teachers successfully form with students are crucial to connect students to school, create a sense of community, and support their growth and learning.§ To the public, the good school is characterized by a positive ethos and climate and well-behaved children and youth. Deciding which behaviors and values are proper and best for students is not a trivial, neutral, or value-free task. Our data here appear to suggest that it is important that teachers have a voice in these larger decisions related to creating the culture, climate, and ethos of their schools.

Richard M. Ingersoll is a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. Philip Sirinides is a senior researcher at the Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) at the University of Pennsylvania. Patrick Dougherty is the associate director of analytics at the New Teacher Center. This article was excerpted from School Leadership, Teachers’ Roles in School Decisionmaking, and Student Achievement, published by CPRE and available online.. The research study summarized in this article was supported by a grant (#B9060) to the New Teacher Center from the Carnegie Corporation. Special thanks are due to Ann Maddock, senior policy advisor from the New Teacher Center, without whom this study would not have been possible.

*For more on teacher-powered schools, see “Leadership for Teaching and Learning” in the Summer 2016 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

†For more on the interrelation among social, emotional, and academic learning, see “The Evidence Base for How Learning Happens” in the Winter 2017–2018 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

‡See, for example, PDK International’s annual poll of the public’s attitudes toward public schools. (back to the article)

§For more on the importance of relationships, see “It’s About Relationships” in the Winter 2015–2016 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. For a review, see Dallas Hambrick Hitt and Pamela D. Tucker, “Systematic Review of Key Leader Practices Found to Influence Student Achievement,” Review of Educational Research 86 (2016): 531–569.

2. Karen Seashore Louis et al., Learning from Leadership: Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning; Final Report of Research to the Wallace Foundation (St. Paul: University of Minnesota Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement, 2010).

3. Richard F. Elmore, Building a New Structure for School Leadership (Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute, 2000).

4. Anthony S. Bryk and Barbara Schneider, Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002); Henry May, Jason Huff, and Ellen Goldring, “A Longitudinal Study of Principals’ Activities and Student Performance,” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 23 (2012): 417–439; and Jonathan Supovitz, Philip Sirinides, and Henry May, “How Principals and Peers Influence Teaching and Learning,” Educational Administration Quarterly 46 (2010): 31–56.

5. Leading Educators, Teacher Leader Competency Framework (New Orleans: Leading Educators, 2015); and Kaitlin Pennington, New Organizations, New Voices: The Landscape of Today’s Teachers Shaping Policy (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2013).

6. Barnett Berry, Ann Byrd, and Alan Wieder, Teacherpreneurs: Innovative Teachers Who Lead but Don’t Leave (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013); Kim Farris-Berg, Edward Dirkswager, and Amy Junge, Trusting Teachers with School Success: What Happens When Teachers Call the Shots (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2013); Beth Hawkins, “Teacher Cooperatives: What Happens When Teachers Run the School?,” Education Next 9, no. 2 (Spring 2009): 37–41; Education Evolving, The Other Half of the Strategy: Following Up on System Reform by Innovating with School and Schooling (St. Paul, MN: Education Evolving, 2008); and Ted Kolderie, The Split Screen Strategy: How to Turn Education into a Self-Improving System (Edina, MN: Beaver’s Pond Press, 2015). For more on teacher-powered schools, visit the Teacher-Powered Schools Initiative at www.teacherpowered.org, which links to Education Evolving and the Center for Teaching Quality.

7. May, Huff, and Goldring, “Longitudinal Study.”

8. Richard M. Ingersoll, Who Controls Teachers’ Work? Power and Accountability in America’s Schools (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003).

9. Opinions in this article reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agency. A detailed report of the study, titled School Leadership Counts, is available at http://info.newteachercenter.org/school-leadership-report.

10. New Teacher Center, “The Impact of Teaching and Learning Conditions on Student Performance and Future Employment Plans” (Santa Cruz, CA: New Teacher Center, 2013), www.tellmass.org/uploads/File/MA12_brief_ach_ret.pdf.

11. Ingersoll, Who Controls Teachers’ Work?; Richard M. Ingersoll, “Power, Accountability, and the Teacher Quality Problem,” in Assessing Teacher Quality: Understanding Teacher Effects on Instruction and Achievement, ed. Sean Kelly (New York: Teachers College Press, 2012), 97–109; and Richard M. Ingersoll and Gregory J. Collins, “Accountability and Control in American Schools,” Journal of Curriculum Studies 49 (2017): 75–95.