One sunny day in May, Ms. Brown tells her first-grade class, “OK, boys and girls, it’s time for recess.” As the children leave the classroom in an organized fashion, three other first-grade classes join them out on the playground, an open field with one tree and a six-foot-tall monkey bar structure. Under the teachers’ watchful eye, the children climb and play.

After 15 minutes, one of the teachers blows a whistle, and the children run back to the building, where another teacher leads them in. Aside from a few latecomers to the door, every child has entered the building in less than 30 seconds. Back in the classroom, Ms. Brown begins a song about not dawdling, and the children move to the carpet for a group story discussion.

Earlier that day, Ms. Brown wasn’t so sure all of her students should go to recess. Connor had acted out one too many times, and she was thinking he didn’t deserve to go out and play. But then, she remembered her training last spring and summer with LiiNK trainers (a project described later in this article), who urged her not to withhold recess as punishment.

So when recess arrived, Ms. Brown decided to allow Connor to go out; she even let him be the first student out the door. The break from his desk ends up helping him refocus. Upon returning to the classroom, Connor apologizes to Ms. Brown and promises to behave better. She believes it. The rest of the day is pleasant for her and Connor—indeed, for the whole class.

While denying recess to a misbehaving student is common for many teachers, Ms. Brown’s response may not be. Her decision to allow Connor to attend recess and his subsequent apology show the power of unstructured play time for students during school.

What Is Recess?

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in its 2013 policy statement titled “The Crucial Role of Recess in School,” describes recess as “a necessary break in the day for optimizing a child’s social, emotional, physical, and cognitive development.”1 Recess ought to be safe and well supervised, yet teachers do not have to direct student activity. The frequency and duration of breaks should allow time for children to mentally decompress, and schools should allow students to experience recess periods daily.

As the AAP makes clear, outdoor play “can serve as a counterbalance to sedentary time and contribute to the recommended 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day.”2 An effective recess is one where children demonstrate their ability to stay within the boundaries of their play space, negotiate conflict with each other, and then return to academic learning. The peer interactions that take place during recess allow for communication, cooperation, and problem solving, complementing the classroom experience.3 Unstructured play, with adult supervision, gives children the opportunity to develop important social and emotional skills, which is essential to a well-rounded education.

The AAP’s policy statement on the role of recess in school cited four critical benefits of recess: (1) greater levels of physical activity and fitness, (2) improved attentiveness in class, (3) improved cognition and learning, and (4) practice of peer-to-peer social and emotional skills. The latter, often overlooked, is cited by child development experts as a fundamental skill set, laying the basis for social success in later life. As a result, the AAP concluded that “recess should be considered a child’s personal time, and it should not be withheld for academic or punitive reasons.”4

After all, “it is the supreme seriousness of play that gives it its educational importance,” said Joseph Lee, the father of the playground movement. “Play seen from the inside, as the child sees it, is the most serious thing in life. … Play builds the child. … Play is thus the essential part of education.”5

A Harvard-educated author and philanthropist, Lee advocated for playgrounds in city schools and parks in the late 19th and early 20th century. He was a leader in promoting school attendance and safe havens for play for all children, especially poor children in the urban core of Boston. In the 1890s, children were forbidden from playing games in the streets and there were no playgrounds in the poorest neighborhoods, where adolescent boys were routinely arrested for delinquency. Lee was from a wealthy Boston family, and, recalling the childhood he experienced—one filled with games, dancing, and play—he took it upon himself to find a solution. He gained permission to clear a vacant lot and provide materials and equipment he felt children would be likely to play with or on, such as dirt piles, large pipes, and sand. And, as he predicted, children came to play.

Over the next decades, Lee’s initiative spread from Boston to Chicago and extended into municipal investment in parks and recreation centers for boys and girls. Lee’s efforts also extended to public education. He was determined that poor children receive the same kind of educational opportunity in schools as their more affluent peers by being educated by teachers who were trained as teachers. He personally underwrote the creation of Harvard University’s School of Education in 1920. It was during this period of growth in urban education and play space for children that recess—as a time during the school day for children to play in a designated space—came to be.6

Lee’s vision of play in education still resonates today. Given that the new federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) removes the emphasis on high-stakes standardized testing in schools and includes nonacademic indicators as a component of a student’s “well-rounded education,”7 schools that have narrowly focused on scores to the detriment of students’ well-being can now correct the imbalance. In doing so, they can ensure that recess, which plays a vital role in social and emotional development, maintains its rightful place in the school day.

The Current State of Recess

Beyond Lee’s advocacy of playgrounds and recreation, it is difficult to document a precise history of recess. In fact, when the School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS) was initiated in 1994 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with the purpose of providing “the first in-depth description of policies and programs related to multiple components of the school health program at the state, district, school, and classroom levels,”8 recess was not included.

It wasn’t until 1997 that the CDC defined recess as “regularly scheduled periods within the elementary school day for unstructured physical activity and play.”9 Recess was first included in the 2000 SHPPS, among various opportunities in schools for children to engage in physical activity. Prior to that, what we know about recess as an experience during the school day—an experience of childhood—is something that is informed by individual and collective memories.

Since then, in addition to SHPPS, other published research about recess practices and policies in the United States has included studies on a smaller scale, in a school or district. These explore various aspects of recess, under the assumption that recess is a given for every child in that school or district.10 Few studies, however, actually examine how recess varies within and across schools and districts (for instance, how teachers monitor and handle recess in the same school and grade).

Largely, the documentation of what happens in the daily, lived experience of recess in schools remains uneven and takes the form of blog posts, news stories, and other social media sharing. The limitations of understanding the delivery and experience of recess at individual schools aside, since the mid- to late-1990s, a growing body of evidence has emerged about the value of and practices and policies related to physical activity—of which recess is one part. Since its inception in 1994, SHPPS has been repeated in 2000, 2006, 2012, and 2014.

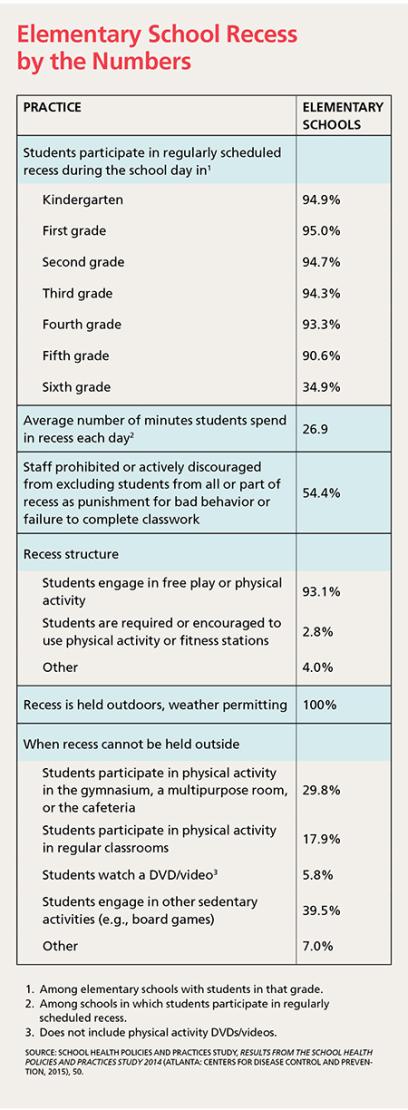

According to SHPPS data from 2014, “82.8 percent of elementary schools provided daily recess for students in all grades in the school.”11 (For a summary of current recess practices, see the table below.) Because this study surveys principals and “lead health education teachers,” this statistic doesn’t necessarily paint a complete picture of where, when, or how recess is provided,* and the documentation about current practices only includes data collected from those schools that reported having regularly scheduled recess. Even with these limitations, however, the 2014 SHPPS research is useful. It shows that, among elementary schools with regularly scheduled recess, the percentage of schools providing recess decreases from first to sixth grade. The average number of days with recess per week across all grades was 4.9, and the average time spent in recess was 26.9 minutes per day.

(click image for larger view)

Decisions about timing, duration, location, and activities for recess are typically made at the school or grade level. While there is no recommended duration (minutes per day) or timing for recess, one of the largest studies published on recess found that for 8- to 9-year-olds, at least one or more daily recess periods of at least 15 minutes was associated with better class behavior ratings from teachers than no daily recess or fewer minutes of recess.12

According to SHPPS data from 2000 to 2014, among schools that offer recess, the percentage of classes having regularly scheduled recess immediately after lunch decreased from 42.3 percent in 2000 to 26.2 percent in 2014. This may be a result of a decrease in recess opportunities, or it may reflect schools’ shifting recess times to before lunch, which has been shown to increase meal consumption and decrease food waste, while improving lunchroom behavior and increasing attention in the classroom following lunch.13

A comparison of results from the SHPPS surveys in 2006 and 2014 also indicates an alarming trend: in 2006, 96.8 percent of elementary schools provided recess for at least one grade in the school, compared with 82.8 percent in 2014. Using self-reported data from high-level administrators at the district level, these surveys show that even though more than 80 percent of districts claim to provide daily recess, a 2014 analysis conducted by the CDC and the Bridging the Gap research program revealed that 60 percent of districts had no policy regarding daily recess for elementary school students and that only 20 percent mandated daily recess.

Additionally, a 2006 analysis by the National Center for Education Statistics found noticeable disparities:14

- City schools reported the lowest average minutes per day of recess (24 minutes in first grade to 21 minutes in sixth grade).

- Rural schools reported the highest average minutes per day (31 minutes in first grade to 24 minutes in sixth grade).

- The lowest minutes per day of recess (21 minutes in first grade to 17 minutes in sixth grade) occurred in schools where 75 percent or more of the students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Decreased opportunities for recess have been associated with increased academic pressure. Recess has been the victim of the perceived need to spend more time preparing students for standardized testing and, generally, to meet increased demands for instructional time. Diminishing recess first began in the early 1990s, and it further declined with the enactment of No Child Left Behind in 2001, which emphasized English language arts and mathematics. To focus on these core areas, districts reduced time for recess, art, music, physical education, and even lunch.15 In addition, recess often was and is withheld from students as punishment for disruptive behavior and/or to encourage task completion, even though research shows this practice “deprives students of health benefits important to their well-being.”16

Interestingly, the emergence of a national health crisis in the United States—the rising rates of obesity in children—has sparked a reevaluation of recess. Recess was included, along with physical education and other opportunities for school-based physical activity, in the wellness policy requirement enacted in 2004 as part of the Child Nutrition and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Reauthorization Act.† (But, as we just noted, a recess-specific policy is lacking in 40 percent of school districts.) In 2014, this requirement was bolstered by an approved rule under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010,17 which “expands the requirements to strengthen policies and increase transparency. The responsibility for developing, implementing, and evaluating a wellness policy is placed at the local level, so the unique needs of each school under the [district’s] jurisdiction can be addressed.”18 By June 30, 2017, all schools/districts must have a wellness policy that meets all required components.

In conjunction with these federal initiatives, some state legislatures have explored recess as part of a broader school-based wellness or physical activity education bill. Accurately documenting what these legislative actions mean for recess is difficult, partially because recess could fall under a variety of laws or policies, and also because the way the law or policy is written can vary. (For example, a mandate may require a set number of minutes per day for physical activity, with recess included, or it might require recess be specifically included in a district wellness policy.)

To supplement CDC and SHPPS information, the National Association of State Boards of Education’s State School Health Policy Database is updated as states enact or revise laws and policies. Within states, districts can add to or build on any federal or state requirement.‡ A similar database does not exist for district-level school health policies, but as indicated by Bridging the Gap’s research, such policies often do not include recess.

With the renewed emphasis on a “well-rounded education” thanks to ESSA, states and schools now have additional incentive to elevate policies and practices for regular recess as part of a robust package of “nonacademic” health and physical activity initiatives, which research has shown to positively affect academic progress.

ESSA requires states to select at least one nonacademic indicator that each school district will report. Funds for implementing the federal law will be allocated to the states to distribute, and they include funds for professional development and programs to support students’ physical health as well as their mental and behavioral health. Recess offers a unique way to address both.

Integrating Recess into School Culture

In 2011, the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) announced it would reintroduce daily recess in the 2012 school year, making it “the first large urban district to once again require daily recess at the elementary and middle school levels.”19 This move was prompted by a groundswell of parents, community members, and concerned district employees, who led the push for recess reinstatement during their struggle to lengthen the school day. We could find no published accounts on the decision to eliminate recess in the first place; however, based on the timing (recess was discontinued in the early 1980s), we can surmise it was both a cost-cutting measure and a response to concerns that students spend as much time as possible on academics.

Thus, in the fall of 2012, when CPS extended the school day by at least 30 minutes across the district, recess once again became a daily occurrence at all elementary and middle schools. Exactly how these minutes are used varies at each school, but reinstating recess did not take away instructional time. Once recess was reinstated, the CPS Office of Student Health and Wellness codified daily recess by making it a provision of the district’s Local School Wellness Policy that was passed in 2012, which mandates that all CPS K–8 students receive a minimum of 20 minutes of recess each day.20 The office provides ongoing support for teachers and administrative personnel to engage in daily recess and other wellness practices. Reinstating recess not only required dedicating the time for it but also required training and resources for schools and teachers to ensure it was safe and consistent across a large number of schools in a wide variety of neighborhoods.

More recently, in September 2015, the Seattle Public Schools and the local teachers union agreed to a guaranteed minimum of 30 minutes of daily recess for elementary school students, although teachers had originally asked for 45 minutes.21

Such changes in recess require schools to rearrange schedules. But even in districts where recess is required, how students experience it is sharply inequitable, as demonstrated at Detroit’s Spain Elementary-Middle School, where “students are forced to walk the halls during recess, because the gym is shut down due to mold and the outdoor playground emits burning steam—even during Detroit snowstorms.”22§ Children in poverty also have less access to free play, fewer minutes of physical activity during the day, and the fewest minutes of recess in school.23

Promising Programs

Ongoing research continues to expand our understanding of why recess and play are crucial. Some studies are exploring play spaces, specific activities, and the benefits of close supervision, while others are examining the benefits of accumulated physical activity and social interactions. While much is being learned from practices in other countries, three programs in the United States are particularly instructive: Peaceful Playgrounds, Playworks, and the Let’s Inspire Innovation ’N Kids (LiiNK) Project out of Texas Christian University. Each offers a slightly different philosophy and approach, but the commonalities are that recess is well supervised and that every child experiences daily, safe play time during the school day. Each program is annually evaluated, and findings have demonstrated the benefits of recess as a component of a whole-child education.

Peaceful Playgrounds began in 1995 and is grounded in the following principles: teaching conflict resolution, establishing clear rules and expectations, providing low-cost equipment, and designing a play space that invites exploration and interaction and minimizes potential for conflict. Peaceful Playgrounds offers training for school personnel in the wealth of games available to children and provides blueprints, playground stencils, and playground game guides. The program emphasizes free choice by students.

Playworks, which began in 1996 as Sports4Kids, focuses on using safe play and physical activity during recess and throughout the day to improve the climate at low-income schools. The program offers a variety of services that hinge on training or providing Playworks “coaches” to “enhance and transform recess and play into a positive experience that helps students and teachers get the most out of every learning opportunity.” According to a survey of Playworks schools, staff report a decrease in bullying and disciplinary incidents, an increase in students’ physical activity during recess, and an increase in students’ abilities to focus on class activities.24

The LiiNK Project, a school curriculum modeled after one in Finland (whose academic performance consistently ranks in the top five countries in the world—well above the United States), was created three years ago to balance a focus on academics and the social and emotional health of children and teachers. Ms. Brown, the first-grade teacher mentioned earlier, teaches in a LiiNK school.

While LiiNK received national media attention in 2016 as strictly a recess program, it emphasizes more than just embedding additional recess into the school day. It also focuses on preparing teachers and administrators to redesign learning environments through recess, character education, and teacher training, in order to combat critical issues affecting the development of noncognitive skills, such as empathy in students.25 Preliminary pilot data are compelling: in schools implementing the LiiNK curriculum, student achievement significantly improved, as did students’ listening, decision-making, and problem-solving abilities.26

Other recess practices, both in the United States and in other countries, have demonstrated positive effects for students and teachers. As discussed previously, the move to conduct recess before lunch is associated with decreased food waste, increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, and better behavior in the lunchroom and upon returning to the classroom.

In studies with British children, providing large equipment and playground markings increased physical activity levels.27 A study in Belgium found a similar effect on physical activity levels through providing smaller, less costly games and equipment.28 Across the globe, simply providing these kinds of portable play equipment, such as balls and jump ropes, encourages children to be active during recess.29

Holding recess outside invites self-directed play where children choose what to do, from playing make-believe games, to reading or daydreaming, to socializing and engaging in physically active games; the experience is up to the child. Certainly, these activities can also occur in an indoor setting, but the opportunity for exploration is limited.30 Interestingly, a large controlled study in China found that outdoor recess may help prevent or minimize nearsightedness in children.31

Meanwhile, children in Japan experience recess in five- to 10-minute bouts approximately every hour, based on the premise that a child’s attention span wanes after 40 to 50 minutes of academic instruction.32

Given the evidence of the value of recess for children and teachers, what can educators, schools, and districts do to promote this critical aspect of the education of the whole child? Daily decisions about who gets recess and when and where it will happen are often made by teachers; thus, teachers are a crucial link for recess. Policies that support daily recess for all children are also essential, especially when it comes to the practice of withholding some or all of recess for disciplinary reasons.33

It is imperative to treat recess time as a child’s personal time (similar to the way adults take breaks and choose how to spend them) and to make this explicit in policy and in practice. Recess time should not be usurped to fulfill a physical activity requirement. That is, if the school is required to offer opportunities outside of physical education classes, recess should only be included as an optional or supplemental opportunity. During recess, it should be as acceptable for children to engage in other types of play as it is for them to engage in physical activity. In addition to policy, teachers, administrators, and school staff would benefit from coursework during initial preparation, as well as from ongoing professional development, in recess management and in establishing and carrying out alternatives to discipline other than withholding recess.

Other ways to promote recess include:

- Advocating for district and school policies that require or recommend daily recess for every child.

- Disseminating information on the benefits of recess and the successful programs and practices described above.

- Including recess-type games and the practice of conflict resolution in physical education teacher training and in school physical education curricula.**

- Encouraging state and district boards of education to integrate the social and emotional benefits of recess in health education curricula.

- Collaborating with school wellness councils, school health and wellness teams, and parent-teacher groups to reinforce policies for recess, fund the purchase and maintenance of playground or recess equipment, and train playground monitors and teachers.

Daily recess for every child supports a school’s mission of providing a high-quality, comprehensive, and meaningful education so students grow and reach their full potential. Participating in recess offers children the necessary break to optimize their social, emotional, physical, and cognitive development. It not only helps them get important daily physical activity but also requires them to engage in rule-making, rule-following, and conflict resolution with peers. These are essential life skills that children can learn to master through the serious act of play.

Catherine Ramstetter is the founder of Successful Healthy Children, a nonprofit organization focused on school health and wellness. A member of the Ohio chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Home and School Health Committee, she has researched and written about the importance of recess to children’s development. Robert Murray is a professor of human nutrition in the College of Education and Human Ecology at the Ohio State University. A former chair of the Ohio AAP chapter, he was previously a professor in the department of pediatrics in the university’s College of Medicine.

*To see the original questionnaires given to principals and teachers, visit the CDC's website. (back to the article)

†The wellness policy language only includes recess as one of the ways schools can address student physical activity. Schools are only required to have a policy that addresses nutrition services, nutrition education, physical education, and physical activity. The federal law does not prescribe the duration, timing, or type of activities. Some states have laws, some have recommendations that are codified, and some have nothing (which is the case for recess in most states). (back to the article)

‡For a state-by-state listing of recess policies in schools, see the NASBE's website. (back to the article)

§For more on health and safety in schools, see “A Matter of Health and Safety” in the Winter 2016–2017 issue of American Educator. (back to the article)

**Physical education is intended to impart not only sport-specific physical and competition skills but also lifelong physical health skills, like rule and goal setting, rule following, and general fine and gross motor skills. While separate from recess, physical education is one class that offers a place where children can learn recess-type games, or games that require imagination and physical movement, as well as appropriate ways to negotiate conflict with others. (back to the article)

Endnotes

1. American Academy of Pediatrics, “Policy Statement: The Crucial Role of Recess in School,” Pediatrics 131, no. 1 (2013): 186.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics, “Policy Statement,” 186.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics, “Policy Statement,” 186.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics, “Policy Statement,” 186.

5. Joseph Lee, Play in Education (New York: Macmillan, 1915), 3–7.

6. The history of Joseph Lee’s life is informed by Donald Culross Peattie, Lives of Destiny: As Told for the “Reader’s Digest” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954), 80–88.

7. Every Student Succeeds Act, Pub. L. No. 114-95, § 8002(21), 129 Stat. 2099 (2015).

8. Lloyd J. Kolbe, Laura Kann, Janet L. Collins, Meg Leavy Small, Beth Collins Pateman, and Charles W. Warren, “The School Health Policies and Programs Study (SHPPS): Context, Methods, General Findings, and Future Efforts,” Journal of School Health 65 (1995): 339.

9. Promoting Better Health for Young People through Physical Activity and Sports (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Education), app. 7, accessed January 19, 2017, www.thenewpe.com/advocacy/promotingPA.pdf.

10. A notable exception explored the effects of recess in one classroom in a school that had eliminated recess. See Olga S. Jarrett, Darlene M. Maxwell, Carrie Dickerson, Pamela Hoge, Gwen Davies, and Amy Yetley, “Impact of Recess on Classroom Behavior: Group Effects and Individual Differences,” Journal of Educational Research 92 (1998): 121–126.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “School Health Policies and Practices Study: 2014 Overview” (Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015), 1.

12. Romina M. Barros, Ellen J. Silver, and Ruth E. K. Stein, “School Recess and Group Classroom Behavior,” Pediatrics 123 (2009): 431–436.

13. Ethan A. Bergman, Nancy S. Buergel, Annaka Femrite, Timothy F. Englund, and Michael R. Braunstein, Relationship of Meal and Recess Schedules to Plate Waste in Elementary Schools (University, MS: National Food Service Management Institute, 2003); Montana Office of Public Instruction School Nutrition Programs, Pilot Project Report: A Recess before Lunch Policy in Four Montana Schools, April 2002–May 2003 (Helena: Montana Office of Public Instruction, 2003); and Joseph Price and David Just, “Lunch, Recess and Nutrition: Responding to Time Incentives in the Cafeteria” (paper, Social Science Research Network, December 9, 2014), doi:10.2139/ssrn.2536103.

14. Basmat Parsad and Laurie Lewis, Calories In, Calories Out: Food and Exercise in Public Elementary Schools, 2005 (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2006), 62.

15. Jennifer McMurrer, Instructional Time in Elementary Schools: A Closer Look at Changes for Specific Subjects, From the Capital to the Classroom: Year 5 of the No Child Left Behind Act (Washington, DC: Center on Education Policy, 2008).

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Guidelines for School and Community Programs to Promote Lifelong Physical Activity among Young People,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 46, no. RR-6 (March 7, 1997): 12.

17. Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-296, § 204, 124 Stat. 3216 (2010).

18. “Local School Wellness Policy Implementation under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010: Summary of the Final Rule,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, July 2016, accessed December 15, 2016, www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/tn/LWPsummary_finalrule.pdf.

19. “CPS’ Daily Recess Is More Than Just Play,” Healthy Schools Campaign, February 17, 2015, www.healthyschools campaign.org/chicago-focus/cps-daily-recess-is-more-than- just-play-5395.

20. “Local School Wellness Policy for Students,” Chicago Public Schools Policy Handbook, § 704.7, October 24, 2012, http://policy.cps.edu/download.aspx?ID=81.

21. Rachel Lerman, “Seattle District, Teachers Agree to Higher Pay for Subs, Longer Recess, but Strike Could Still Happen,” Seattle Times, September 6, 2015.

22. Katie Felber, “Heartbreaking Video Depicts Harsh Reality of Detroit Public Schools,” Good, January 19, 2016, www.good.is/videos/heartbreaking-video-detroit-public-schools.

23. Parsad and Lewis, Calories In, Calories Out.

24. “2016 Annual Survey Results—National,” Playworks, accessed December 8, 2016, www.playworks.org/about/annual-survey/national.

25. Debbie Rhea, “Recess: The Forgotten Classroom,” Instructional Leader 29, no. 1 (January 2016): 1.

26. Rhea, “Recess”; and Deborah J. Rhea, Alexander P. Rivchun, and Jacqueline Pennings, “The Liink Project: Implementation of a Recess and Character Development Pilot Study with Grades K & 1 Children,” Texas Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance Journal 84, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 14–17, 35.

27. Nicola D. Ridgers, Gareth Stratton, Stuart J. Fairclough, and Jos W. R. Twisk, “Long-Term Effects of a Playground Markings and Physical Structures on Children’s Recess Physical Activity Levels,” Preventative Medicine 44 (2007): 393–397.

28. Stefanie J. M. Verstraete, Greet M. Cardon, Dirk L. R. De Clercq, and Ilse M. M. De Bourdeaudhuij, “Increasing Children’s Physical Activity Levels during Recess Periods in Elementary Schools: The Effects of Providing Game Equipment,” European Journal of Public Health 16 (2006): 415–419.

29. Nicola D. Ridgers, Jo Salmon, Anne-Maree Parrish, Rebecca M. Stanley, and Anthony D. Okely, “Physical Activity during School Recess: A Systematic Review,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43 (2012): 327.

30. Deborah J. Rhea and Irene Nigaglioni, “Outdoor Playing = Outdoor Learning,” Educational Facility Planner 49, nos. 2–3 (2016): 16–20.

31. Mingguang He, Fan Xiang, Yangfa Zeng, et al., “Effect of Time Spent Outdoors at School on the Development of Myopia among Children in China: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA 314, no. 11 (2015): 1142–1148.

32. Harold W. Stevenson and Shin-Ying Lee, “Contexts of Achievement: A Study of American, Chinese, and Japanese Children,” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 55, nos. 1–2 (1990).

33. Lindsey Turner, Jamie F. Chriqui, and Frank J. Chaloupka, “Withholding Recess from Elementary School Students: Policies Matter,” Journal of School Health 83 (2013): 533–541.

[illustrations by Liza Flores]