While studying comparative literature in graduate school, I woke up one day and realized I needed to choose a career path. I made a list of various possibilities based on two criteria: I wanted to be able to support myself anywhere in the world, and I wanted to complete whatever studies the career required in a short amount of time. It may seem pretty odd based on my interest in literature, but I put nursing on the list. Having never been inside a hospital or around anyone seriously ill, I knew very little about nursing as a career choice, but it seemed to fulfill my criteria. In the end, it was the path I chose.

The next step was figuring out how to become a nurse. From watching TV, it seemed to me as though all nurses went through hospital-based training programs. But someone told me about a two-year bachelor of science in nursing program that had an expansion grant specifically targeting students like me with a bachelor’s degree in another area. I applied and was accepted to the program at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York, and I earned my initial nursing degree in 1976 (I now also hold a master’s degree in nursing and am a pediatric nurse practitioner as well as a child and family clinical nurse specialist). Since then, I have enjoyed a 40-year-long (thus far!) career that I have never regretted for a moment.

My first nursing position was at Roosevelt Hospital in New York City. I specialized in pediatrics and pediatric critical care for more than 20 years before finding myself as a school-based healthcare provider. Throughout my career, I have met the goals I initially set for myself when I first made my list: I have worked in Peru, Mexico, Ecuador, Nepal, and Israel, as well as in New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and California.

When I became a mother in 1996, the middle-of-the-night phone calls from the hospital saying “You need to come in” became more of a challenge. I realized I needed a position where I could work daytime hours within my field of expertise and still have time to spend with my family. When I saw a posting for a school nurse position in the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD), I applied.

Since January of 1997, I have been a school nurse. In SFUSD, I have worked at both the elementary and secondary levels, and, over the years, my assignments have varied greatly. There were years when I worked in one high school and two middle schools, and there was one year when I had a different site each day. Luckily, for the past five years, I have been at one secondary-level site full time—the Galileo Academy of Science and Technology, a large urban high school with nearly 2,000 students.

As you can imagine, being spread thin with minimal time at multiple sites was pretty awful. It was difficult to build relationships with students and families and to connect with faculty and staff. Being at a single site has allowed me to develop ongoing and meaningful relationships and engage with the wider community.

Unfortunately, school nurses are not mandated in California schools, and not all SFUSD schools have nurses based on site. While nearly 40 nurses work in the district, SFUSD enrolls more than 57,000 students at more than 130 schools. Based on recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, I should not be the only nurse at Galileo. The school should have two full-time nurses assigned, and another working with us a few times a week!

While some schools in SFUSD have a full-time nurse on a daily basis, the degree of need in every school is quite high. I fully believe in the American Federation of Teachers’ position that every child should have access to a school nurse. I would also add that every child deserves a school nurse. In SFUSD, as in many school districts around the country, there is not a nurse in every school—and there should be.

No Typical Day

Contractually, I work a seven-hour day, but, as with most of us in educational settings, my day extends beyond those hours. One of the things that I like best about working as a school nurse is that there is no “typical” day. While I may have standing meetings scheduled on given days or prescheduled student-focused meetings, I cannot plan for events that pull me from scheduled meetings or for situations that show up on my doorstep. I never know if there is going to be a major emergency or a situation where a student is in dire need of a trusted adult willing to listen to his or her concerns.

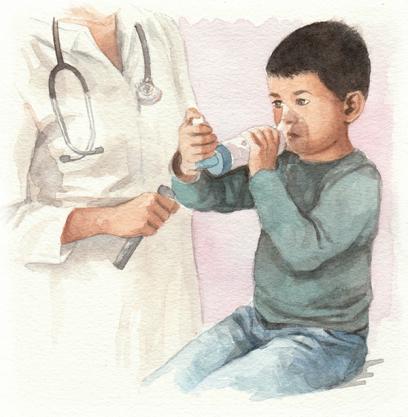

A big piece of my job is attending to the physical health of students. Some students who come into my office do not have a primary care practitioner or have not seen a healthcare provider in years. If something is wrong with them, I have to discern what it might be and what additional services they may need, and then connect those students with those services. I follow students with chronic illnesses, such as those who have asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, or other disorders that may affect them (and their performance) at school. There are also the emergencies—the student who gets hurt on the field during gym, the student who slips on the stairs, the student who faints, and so on.

I also see many students with mental health challenges. Often, mental health issues will manifest physically, or students will claim a physical ailment in order to avoid the stigma they may feel around admitting a mental health concern. For many students, saying they have a headache or a stomachache is a safe way for them to leave class and come to the nurse’s office. As we talk and issues surface, I may realize they are struggling with depression or anxiety or with difficulties at home. I then connect them with on-site services or refer them to outside providers.

I also deal with social ills plaguing many of our students. For example, I have worked with many students in unstable housing situations. Sometimes, they’ve been evicted from their homes and are living four or five in a room in a shelter with no privacy. These students sometimes come to my attention when they are referred by teachers because they appear disheveled or their personal hygiene needs are not being met. I may use my stethoscope to examine students, but I mostly rely on my assessment skills, years of experience, and gut feelings to determine what kinds of help our students need.

I remember one student in particular who came from a home rife with domestic violence and drug abuse. He was in and out of foster care, and his school attendance was suffering. People at school were really worried about him. For school nurses, unfortunately, this is not an uncommon story. He was initially referred to me because of personal hygiene issues, but our relationship expanded to include discussion of his dreams and aspirations as well as his life challenges. Over the course of his four years at school, I worked closely with him to ensure his physical and mental health didn’t prevent him from achieving academic success. Not only did I watch him graduate on time, I worked with him to consider his life beyond high school. I encouraged him to attend college and helped him make that dream a reality with enrollment at Tuskegee University. It meant the world to me when he invited me to his college graduation, and I was thrilled to be remembered as someone who influenced his life.

The most rewarding part of my job (and, equally, the most challenging) is working with adolescents. I really enjoy connecting and communicating with them as they blossom into adulthood. They have insight. They have awareness. The great reward is to watch that process in “real time” while working one-on-one with them.

The real challenge is that they’re still teenagers, constantly testing limits. They may hear what I have to say, but they don’t always listen. Sometimes a student will confide in me, and, as I’m listening with my nonjudgmental face, as a mom, my brain is screaming, “You did what?” Sometimes, I’m the only adult that students trust. Sometimes, I’m the only adult who gives them the time of day. I consider it a privilege and an honor to work with them.

I am here for faculty and staff as well. I provide individual consultations on health issues they may be facing, including helping to monitor ongoing conditions such as elevated blood pressure. I answer questions on how to navigate healthcare systems as well as sometimes providing information related to the health of their own children. I also offer professional development opportunities and workshops on topics such as meeting the needs of bereaved children in school settings (for which the AFT provided training).

I’m especially proud of the success our district has enjoyed around reproductive health. In SFUSD, school nurses have played a major part in the decrease in the teen pregnancy rate.* The California legislature passed a law in 2003 requiring health education to be “comprehensive, medically accurate, and age- and culturally-appropriate.”Our state law allows students 12 years and older to take charge of and responsibility for their reproductive health. To that end, school nurses in SFUSD are often involved in making certain that our students receive accurate information and rapid access to reproductive healthcare.

School nurses in our high schools are also part of the San Francisco Wellness Initiative, which is a partnership among SFUSD, the San Francisco Department of Public Health, and the San Francisco Department of Children, Youth and Their Families. This partnership allows for every high school to have on-site services to respond to the physical and mental health needs of students.

The role of the school nurse in our district is also affected by the receipt of grant funding. Depending on the grant, our roles are expanded or contracted. For example, thanks to a California Tobacco-Use Prevention Education grant, school nurses at the high school level are charged with providing tobacco-use prevention activities and services.

While the Wellness Initiative is a step in the right direction, my dream is for all high schools to become full community schools with full-scope services available not only to students but to their families as well. Fortunately, the city does run health clinics for teenagers throughout San Francisco, so I do refer students to those when they have health needs beyond what I can handle. One such clinic is located very close to our school, and students feel very comfortable going there.

Union Support

I have strong relationships with faculty and staff throughout my school. I am Galileo’s union building representative, and I’ve served on the executive board of the United Educators of San Francisco (UESF) for the last 16 years and on the UESF bargaining team. I’ve been a union member my entire adult working life, both with nonnursing unions and nursing associations.

It was initially strange to learn that I was being represented by a local union mostly made up of teachers and paraprofessionals, and we had a few issues to work through over the course of my first several years in the district. Fortunately, union leadership was open to learning about the needs of nonclassroom personnel, and I was happy to learn about the needs and issues affecting my coworkers in the classroom.

In my time on the UESF executive board, I have worked to ensure that school nurses and other nonclassroom staff are recognized for the work we do and receive equal representation. Proudly, our UESF banner now reflects the wide variety of classifications among its members by stating that we are a union of school professionals.

My first encounter with the union came as a result of my initial placement on the salary scale. Even though I came to the school district with more than 20 years of nursing experience, I was initially placed at the five-year experience level because, according to my then-supervisor, my work outside of schools did not count for much (despite the fact that it had always been with children and families). There were also workday issues, including how many hours we worked, how we worked, and whether the travel time between schools counted toward hours worked—among other basic nuts and bolts of health and welfare issues.

With the support of the UESF, a grievance was filed, and, in the end, 14 nurses had their salaries increased based on their previous nursing experience (regardless of where that experience occurred). Thanks to our union, my colleagues and I succeeded in having our prior experience recognized and rewarded.

The AFT, which is now the second-largest union of nurses in the country, has been a vocal supporter of the vital services school nurses provide. Within the AFT, school nurses belong to the Nurses and Health Professionals division, yet we have the unique position of straddling two worlds as we provide vital healthcare in public schools and, in so doing, directly support the AFT’s educational mission. In the years to come, I hope every student in our country has access to a school nurse every day.

Susan Kitchell is the school nurse at the Galileo Academy of Science and Technology in the San Francisco Unified School District. A former hospital nurse, she has spent nearly 20 of her 40 years in nursing as a school nurse.

*From 2003 to 2013, the teenage birth rate in San Francisco declined from 20.0 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19 to 10.2 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19, a 49 percent decrease (which is above the 41.1 percent decrease statewide for the period). (back to the article)

[illustrations by Enrique Moreiro]