In 2012, Michigan’s Republican governor and Republican-controlled legislature passed a raft of anti-union laws. But the labor movement fought back—and won. To find out how, we spoke with three AFT leaders: David Hecker, Terrence Martin Sr., and Eric Rader.

David Hecker, a member of the AFT since 1977, was the president of AFT Michigan from 2001 to 2023 and an AFT vice president until July 2024. He has served as a co-chair of the AFT Organizing Committee and on the boards of several nonprofits in Michigan. Terrence Martin Sr., who was the president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers from 2018 to 2023, is the president of AFT Michigan and an AFT vice president. He attended and taught in Detroit public schools and remains an outspoken advocate for social, educational, and economic justice in the city. Eric Rader, a political science professor, is the president of the Henry Ford Community College Federation of Teachers, which represents full-time teaching faculty, counselors, librarians, and other academic staff at Henry Ford College in Dearborn. He’s also an AFT Michigan vice president, a member of the AFT Higher Education Program and Policy Council, and a co-chair of the AFT Organizing Committee.

–EDITORS

EDITORS: After more than a decade under anti-union laws, Michigan’s labor movement achieved major legislative victories in 2023. Please share some highlights.

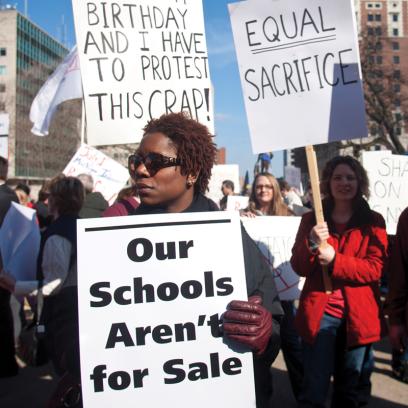

DAVID HECKER: In 2011, the Republican Party had a majority in the state legislature and a conservative governor, Rick Snyder. Together, in 2012, they turned Michigan into a so-called right-to-work state.

Among other issues, they also took away payroll dues deduction for K–12 educators; stripped our right to bargain on a wide range of teacher issues, including placement, evaluations, discipline, and discharge; and declared that graduate research assistants were not covered by labor law. In 2023, we won all that back and more, including overturning right-to-work in the private sector. The public sector, of course, is governed by the US Supreme Court’s Janus decision.*

TERRENCE MARTIN SR.: Winning back some job security for our members was huge. We also won back the right to negotiate wages for teachers in Detroit. Fifteen years ago, the Detroit Public Schools was taken over by the state (for the second time). Two emergency managers focused on cost cutting, school closures, and divestment. They seemed determined to starve the neighborhood public schools and open charters. Conditions in the schools became so bad that our enrollment dropped by half and debt ballooned to $335 million.†

ERIC RADER: Community colleges never lost payroll deduction, but we did lose deductions for our political action fund. My local uses its political action fund for state and local races. Restoring this payroll deduction was important for us because we used to have 90 percent of our members contributing. Now we’re at about 70 percent, so we’re working to build back up. Most of our 2023 legislative victories restored the right to bargain for things we used to have—not the things themselves. I’m going to be negotiating with the college to put payroll deduction for our political action fund back into our contracts.

There was also a restriction in 2012 that affected K–12 and higher education: if your contract expired, steps in your salary schedule did not automatically go into effect, and you had to pay for any additional healthcare insurance premiums. Now, your steps continue even if you haven’t reached an agreement on a new contract, and you don’t have to pay additional money for your healthcare coverage. You can also get retroactive pay. That’s a big one for all of us.

TERRENCE: One more big win was a renewed belief in the labor movement. When we were battling the state to try to get these things returned, it wasn’t just us; it was Michigan’s labor movement that galvanized change by banding together. Now we have a renewed sense of the strength of the labor movement. We can point to specific things that we were able to win together, which prompted people to want to be a part of a union.

EDITORS: Now the million-dollar question: How did you get from devastating losses in 2012 to amazing victories in 2023?

DAVID: There are two answers, one grounded in how we build power, the other in what we do with our power. Fundamentally, our power comes from our members. Power is what matters. For example, unions don’t win strong contracts at the bargaining table. We win by increasing our leverage—our power—through union member and community member activism. The same is true for legislative victories. We build power by mobilizing members around issues, by working with community allies. We build power by having a vision for our union and for what we must and can accomplish.

TERRENCE: That has definitely proven true in Detroit. At the Detroit Federation of Teachers (DFT), since the takeover our vision has been that our school district is worth saving and that every child in the city of Detroit deserves a quality public school in their neighborhood. We discussed our vision with members and community leaders, asking “Will you join us in securing that for our children?” That’s how we built power. We created a coalition of people who believed in the same thing, and eventually we had enough support that elected officials shared our vision too.

It’s not as easy as it sounds. Some people won’t believe in you. But our intentions were pure, and the average Detroit citizen came to understand and believe us—in part because what the emergency managers did was so unbelievable. Because of their divestment, class sizes ballooned, many classes had long-term subs, and some classes had no adult supervision at all. The conditions turned many highly conservative people into public school supporters.

Families and community folks still believe in teachers. They go to teachers for advice. The DFT’s message was believable in part because it was coming from the people who have dedicated their lives to the students of the city of Detroit and who knew firsthand what was happening.

Another crucial lesson I’ve learned is that building power takes time. Too often, we hear about a victorious strike or a new law passed, but we don’t hear about the struggle in the months and years leading up to those moments. There are dark days when you’re arguing with people who are supposed to be on your side. You question your strategies. The journey can be just as important as where you land.

ERIC: I agree. In 2011 and 2012, I was chairing my local’s Political Action Committee (PAC). We had a lot of people who were interested in joining the committee because they didn’t know what else to do. In 2012, we knew the votes in the state legislature were against us, but we still turned out—with the whole Michigan labor movement—in huge numbers at the state capitol to protest.

People were down because they knew how much we had won over the years and what the legislature had stripped away. They were discouraged and not sure how to fight back. In the aftermath, we knew we were not in good shape politically at the local or state levels. In response, my local bargained for a community service requirement. We wanted our members to get involved in service organizations so that people would know us and see us as the face of the college in the community.

That was a long-term strategy for building support. There are many more conservative community members who don’t automatically support labor. By doing community service work side by side, they got to know us as good people teaching their kids. We may still disagree on some issues, but many started to see that there’s value in us having the right to bargain our contracts.

Patience has been critical. We spent 12 years patiently organizing, patiently engaging with the community, patiently getting out the vote, and patiently lobbying.

TERRENCE: The DFT needed to engage members like your local did, but first we had some basic restructuring to do. For years, the DFT was a service-oriented local; we focused on bread-and-butter issues. We were a closed shop, and we won great contracts. That changed with the state takeover. The emergency managers closed schools and fired staff, so we had to organize. We hired two rank-and-file members, released full time, to be organizing fellows in the DFT. They had been activists within our local, volunteering their own time to build the union. With the organizing fellows and our new mindset, we didn’t just take the issues we saw every day to the bargaining table—we took them to the street.

Along with our colleagues at AFT Michigan, we also created a community table that grew into the Michigan Education Justice Coalition. Many nonprofits and community members joined together to fight the emergency managers’ divestment and attempts to charterize the district.

Our members started seeing themselves not just as teachers but as important pieces of the school community, and they saw a way to make things better.

DAVID: Over about 25 years, AFT Michigan made a concerted effort to become an organizing union. Not just organizing externally, but operating under the organizing model, which means involving and mobilizing members. We worked to move the entire state federation in that direction, and now Terrence is continuing that work.

At AFT Michigan, one key strategy has been hiring staff members who think like organizers. The essential questions for all staff are, “How do I do my work in a way that involves our members, that builds the union, makes the union stronger, in every aspect of what we do? How do we have a union where members are involved in all we do: coming to bargaining, meeting with legislators, being involved politically, and forming partnerships with community organizations?”

To build a strong union, there’s always a role for the service model. If there is a crisis that must be addressed immediately, and the union leader can step in and put out the fire, they should. But the default should be the organizing model. Even when addressing an individual need, like filing a grievance, you organize around it by having everyone at the workplace rally or sign a petition in support of their colleague.

The organizing model asks, “How do we empower our members to do the work that needs to be done?” Sometimes that’s a lot more time-consuming than solving the problem yourself as a union leader—but by involving others, you solve the problem and build the union.

Several years ago, we codified what a local union should be doing, how to do it, and how to assess their progress in the power wheel shown below. From the state affiliate perspective, the ideal situation isn’t that our staff is doing everything for local unions. The ideal situation is that we’re empowering locals. That takes time, so we slowly move from heavily supporting new leaders to just checking in with experienced ones and assisting when needed.

To mobilize members into action, union leaders must ensure our members see the connections between the work we ask them to do and how they benefit from the outcomes. When we ask members to donate to our political action funds, knock on doors for endorsed candidates, and volunteer to get out the vote, we must show the difference they can make. People are busy, and we are asking for their time. Our members work hard for their paychecks, and we are asking them to part with some of it for our PAC. When we make an ask of our members, we must put ourselves in their shoes to best be able to determine how we approach them to take action.

ERIC: A lot of people come into our local not wanting anything to do with politics, especially these days. But the people in Lansing (our capital) decide how much funding our college receives and how much we’re going to pay for healthcare. When we send out communications about political campaigns, we focus on issues that are most relevant to the professional work of our members. We talk about funding for our college and other practical bread-and-butter issues. Our focus is on our livelihoods and being able to do our jobs as professionals. We talk about shared governance at the college and our role in deciding policies. And we connect that to being involved in policymaking in Lansing—we don’t want policies pushed down on us.

Even members who are not Democrats are willing to give to our political action fund and help get out the vote by phone banking or going door to door because they know we’re supporting pro–public education candidates. Importantly, our political action fund has a category where people can restrict their contributions to certain races. Some members only want their funds to support races for our board of trustees or the local millage that provides much of our school’s funding. We honor that.

TERRENCE: I agree. But I’ll also add that sometimes there are members who really should be eager to volunteer and donate. In 2024, the people who should be speaking up in favor of the Biden-Harris administration are those who have gotten thousands and thousands of dollars forgiven in student loans. Frankly, those are the folks we’re leaning on when it comes to political action fund donations to get out the vote for Kamala Harris.

EDITORS: You’ve shared a lot about how you built power. What did you do with it?

ERIC: After several years of building community support and labor-friendly coalitions, unions and progressive groups saw an opportunity to fix our gerrymandered state legislature in 2018. Michigan is a purple state, but progressives routinely lost state legislative races because of how the district maps were drawn.

In 2018, we, along with many other progressive groups, pushed a ballot initiative called Voters Not Politicians to shift control of redistricting from the legislature to an independent commission. Our goal was to have districts that actually represent the population. That proved popular. When we went door to door to educate people about the initiative, most people agreed it was a great idea.

After the ballot initiative passed, our work was just beginning. Once the independent commission was formed, it held hearings across the state. AFT Michigan was involved, and I testified for the Dearborn area, along with submitting a proposed map for redistricting. Using data from the 2020 census and information from the hearings, the commission drew more representative boundaries for the districts.

DAVID: There are three main reasons we were successful in the 2022 elections: First, the work we had done building the organizing model, getting more and more members engaged with political action. Second, in 2018, Michigan voters passed two election-related ballot initiatives. One provided for nonpartisan reapportionment, as Eric described. AFT Michigan contributed both money and local union volunteers. Another ballot question in 2018 that we were heavily involved with focused on increasing access to voting. Called Promote the Vote, it provided for early voting, no-reason absentee voting, and straight party voting. If we hadn’t succeeded in increasing voter access and securing nonpartisan redistricting in 2018, we wouldn’t have taken the House and the Senate in 2022. The third reason we were successful was the issue of reproductive rights. Not only did this issue impact candidate races, but in Michigan codifying choice in the state constitution was on the ballot in 2022—and passed.

Then, in preparation for the 2023 legislative session, the president of the Michigan AFL-CIO had all of the AFL-CIO’s member unions vote on a Solidarity Pact that listed the top priorities of the various unions. We pledged that we would all stay in the fight until everybody got what they deserved; a union would not walk away from the legislative arena once it won on its specific issues. We all pledged to stay and fight for each other. And while the Michigan Education Association (MEA) is not in the AFL-CIO, we all worked hand-in-hand.

While unions have always worked together, in my 40 years in the Michigan labor movement and more years in the Wisconsin labor movement, I had never experienced an actual vote on such a Solidarity Pact—a vote that indicated we all understood that the only way to have a strong labor movement was for all of labor to win. We basically said, “No one’s leaving until all of our issues are addressed.”

ERIC: That solidarity meant a lot—and we tried to replicate it at the local level. The Michigan AFL-CIO organized several lobby days for us in 2023. K–12 teachers and staff were still in school during our lobby days in May, while our regular academic year had ended. Though the focus of last year’s lobby days was primarily on K–12 issues, I encouraged our members to get involved because we’re all in it together.

Still, in my local it was a little harder to get people involved in 2023. Since we won the 2022 election, many members felt like their work was done. But helping elect people who understand your issues and share your priorities is only one step in the process. We still have to go to Lansing to remind them why basic things like funding for public education and restoring the right to bargain issues are important.

Now, as we gear up for another election, we’re able to point to all we won in 2022 and 2023—and to remind members that this is a swing state. We can lose it all again if we don’t continue to fight.

TERRENCE: It had been hard to get DFT members involved since the first state takeover 25 years ago. Detroit had been mistreated for so long, and we had lost so much. It was hard to believe that AFT Michigan and the Michigan AFL-CIO were putting us in a position to win.

So we not only lifted up the strategies but also tried to change hearts and minds. Members needed to believe that we could make change by knocking on doors, talking to community members, and gathering signatures for these ballot initiatives. One message we have for people in states like Wisconsin and Florida is “Have hope.” One of the hardest things to do is to get folks who have suffered loss to believe again. We were able to do that here.

DAVID: I think the number one time you really see a labor movement come together is during the political season because, with few exceptions, we all want the same people elected. The Michigan AFL-CIO brings unions together and sets up neighborhood walks and phone banks. AFT Michigan has worked with the AFL-CIO and the MEA doing this work.

ERIC: It’s a huge relief that I don’t have to organize get-out-the-vote activities, rallies, lobby days, or other actions for state or national elections; I just have to find volunteers to participate in what the state affiliates have organized.

However, my local does run campaigns for our local elections and ballot initiatives, such as school board races and efforts to renew our property tax millage funding. Our college’s board of trustees is also the school board for Dearborn; they have a combined role, which is very unique. So we work very closely with the Dearborn Federation of Teachers, the Henry Ford Community College Adjunct Faculty Organization, and the Dearborn Federation of School Employees—all of which are AFT locals. We also collaborate with the non-AFT unions at Henry Ford and in our district.

Because we have this common board, we partner on screening candidates. The locals’ presidents and political coordinators serve on a screening committee that has a set of questions for candidates on issues that are important to our members, like their position on organized labor, the right to strike, and funding for education. Our goal is to make a common endorsement. That hasn’t always happened, but it’s still helpful to be listening to them together and getting the same answers.

We also pool our resources. My predecessor, John McDonald, led us in negotiating strong contracts over several decades. At the same time, he stressed the importance of contributing to our political action fund to allow us to lead campaigns in our area and join with our state federation in statewide races. We had to fight for it, but it still comes with a responsibility to work with our sibling unions. Some of the local unions don’t have the financial resources we have, but their members pledge volunteer hours.

TERRENCE: The importance of this mutual support can’t be overstated. One of the keys to success is having synergy between locals and their state federation. If not for the support that I got from AFT Michigan, the DFT would not have won the district back from the state takeover. And if not for that synergy statewide, we would not have won the Michigan House and Senate.

You’re not always going to agree on every strategy. But after you’ve had an opportunity to voice your perspective, you fall in line with the decision. That unity is what leads to the victories we’ve seen in recent years.

DAVID: I agree with Terrence, but I’ll also say it the other way. What is the state federation? It’s the locals. If the locals were not on board with the state federation’s programs, the state federation would not be able to accomplish anything.

TERRENCE: I remember in years past wishing that one day my local would get to a point where the AFT would want to do a story on our successes. It’s a testament to our collaboration and perseverance that we’re finally seeing that day, and I hope others can learn from what we’ve done.

*To learn more about Janus, see go.aft.org/ogv. (return to article)

†For details on the state takeovers, see go.aft.org/rsk. (return to article)

[photos: AP Photo / Paul Sancya; and AFT]