Writing has many benefits. It can improve children’s speaking, boost their reading comprehension, build their knowledge, and elevate their thinking. But one reason it’s hard to learn is that without explicit writing instruction, children often write the way they speak.

From elementary through high school, many children answer questions with little elaboration. Others tend to ramble on, giving unnecessary information in a disorganized fashion. It’s not unusual to see the same tendencies in their writing. With the strategies shared in this article, your child will be on their way to becoming a clear thinker and coherent communicator—not just in school but for the rest of their life. We can see some of this progress with Michael.

Ms. Worth, mother of 10-year-old Michael, looked forward to hearing about his day at school. However, when asked, Michael always gave the same answer: “Good.”

After reading about the benefits of explicit writing instruction,1 Ms. Worth decided to try an approach that seemed to make sense to her: sentence stems. But she didn’t ask Michael to write; she just added them to their conversation. When Michael provided his usual response, “Good,” she asked him to turn the following sentence stems into complete sentences:

School was good because _____.

School was good, but _____.

School was good, so _____.

Ms. Worth learned that Michael had a good day because his class visited the aquarium. Michael’s day was good, but he had to write about the field trip. Finally, Michael shared “School was good today, so I hope tomorrow is, too.”

Michael was able to provide much more information to his mother when she gave him an approach that incorporated the conjunctions because, but, and so than if she had just asked her usual question, “How was your day?”

Although the because/but/so strategy was developed to help students with their writing, there are great benefits to using it orally, too—especially at home. It gives children a structure to extend and elaborate their verbal responses. And, when children offer their families even a few more details, great conversations are often sparked.

Since the sentence stems worked well, Ms. Worth also started using them to extend Michael’s written responses when she helped him with his homework. She found that this strategy had a great impact when applied to the content he was studying.

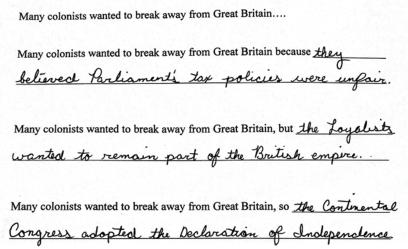

For example, when Michael was learning about the American Revolution in school, he read about the causes of the conflict. Rather than asking “Why did many colonists want to break away from Great Britain?,” Ms. Worth tried checking his understanding by giving him the following sentence stems:

Prompting children with because, but, and so is a simple yet powerful strategy. It requires children to think more analytically, while also teaching them how to extend their written responses.

Writing Complex Sentences

Like so many children, Michael often writes the way he speaks—and the quality of his writing may suffer as a result. Written language generally requires more precision than spoken language because the reader of a text cannot ask for clarification the way a listener can (i.e., when you’re reading a book, you can’t ask the author what a confusing sentence means). In addition, the sentence structure of written language is more complex than the language we generally use in conversation. Writers often use multiple clauses and subordinating conjunctions such as although, since, before, after, and if, especially at the beginning of a sentence. If children are unfamiliar with those structures, they are more likely to struggle with understanding what they read. But when they learn to use more complex sentences in their own writing, their reading comprehension often improves.2 Their writing quality improves as well.

Wanting her son to continue developing as a writer, Ms. Worth helped him practice writing more complex sentences—and in reading his work, she could assess his comprehension of the text he had been assigned on the American Revolution. She gave him the beginning of a sentence, and he needed to supply the rest (Michael’s responses are shown in italics).

After the Sons of Liberty dumped tea in Boston Harbor, Parliament punished the colonists with the Intolerable Acts.

Although the British military was well-equipped, the colonists’ knowledge of the land helped them win the war.

Expanding Sentences

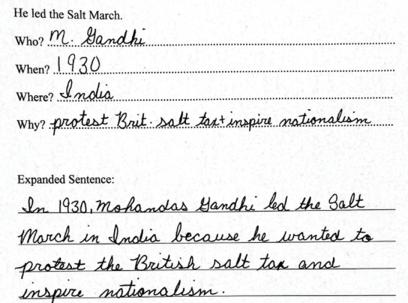

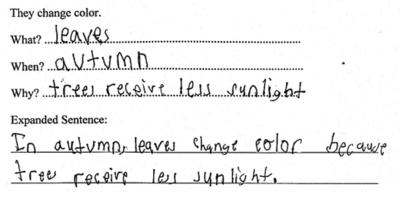

When responding to questions, Michael, like many children, often omits information that he assumes a reader or listener already knows. In the sentence expansion strategy, children add information to a simple sentence, called a kernel, by answering the relevant question words: who, what, when, where, why, and how.

Ms. Worth decided to add this strategy. Michael found it fun to use when given a kernel that allowed him to use his imagination, such as He ran. Practicing it at home improved his writing for school assignments—and his mom enjoyed hearing the answers he’d dream up.

Continuing the revolution theme in his social studies class, Michael was asked to complete a sentence expansion activity about Gandhi leading the Salt March. He knew that when he saw dotted lines under the kernel, he didn’t have to write complete sentences, just key words and phrases. Still, his written responses allowed his mother to check his understanding of the text about Gandhi.

As with the because/but/so activity, parents and caregivers can practice this sentence expansion strategy with their children using academic or everyday content, and in any grade level and subject area. The example below about leaves changing color demonstrates that even first-graders can become adept at expanding sentences.

Planning Paragraphs

One of the most effective ways to make writing easier for children is to teach them how to develop a plan before writing a paragraph. Like the sentence stems and expanders, you can help your child at home by helping them practice using the single-paragraph outline.

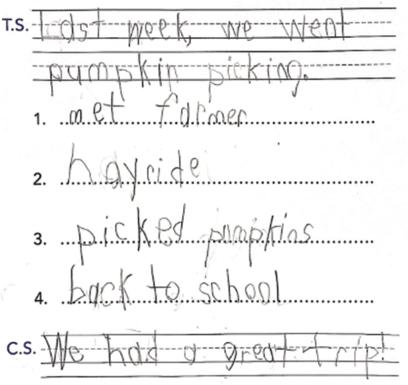

The single-paragraph outline enables even young students to begin developing a coherent paragraph by planning a topic sentence, supporting details, and a concluding sentence. Since this is intended to be a plan—not a draft—just ask your child to write notes on the detail lines, not complete sentences. Here’s an example from a first-grader after an exciting field trip.

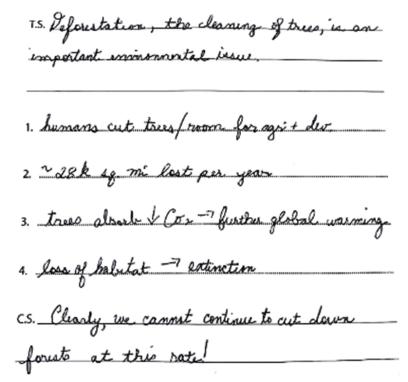

This strategy can even work with preschoolers and kindergartners. If your child isn’t writing yet, have them dictate the most important words and phrases for you to write on the dotted lines. For older children like Michael, this single-paragraph outline still works well. In the following outline about deforestation for a school assignment, Michael used symbols to show relationships between ideas.

While the goal is for your child to be able to develop an outline independently, in the beginning they will need your help in learning how to develop topic and concluding sentences and how to select and sequence appropriate details.

Writing may be the most cognitively demanding academic skill we expect children to master. For many, crafting clear sentences is challenging, and producing paragraphs is even more difficult. Written assignments often require knowledge of the subject matter, awareness of one’s audience, varied vocabulary, logically sequenced information, and a consistent focus on the topic. Fortunately, the strategies in this article, as well as others available for free here, can improve children’s oral and written responses. And, by helping your child with these strategies, you’ll learn a lot more about their experiences, thoughts, and feelings as your prompts encourage them to open up.

Judith C. Hochman, former head of The Windward School in White Plains, New York, is the founder of The Writing Revolution and a coauthor (with Natalie Wexler) of The Writing Revolution: A Guide to Advancing Thinking Through Writing in All Subjects and Grades. Toni-Ann Vroom and Dina Zoleo are co-chief executive officers and founding members of The Writing Revolution.

Endnotes

1. J. Hochman and N. Wexler, The Writing Revolution: A Guide to Advancing Thinking Through Writing in All Subjects and Grades (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2017).

2. C. Scott, “A Case for the Sentence in Reading Comprehension,” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 40 (2009): 184–91.

[illustrations: Jessie Lin]