Teaching a child to read is a science and an art. Fueled by love and joy, songs and word games, everyday conversations, and books, books, books, it’s a multiyear process in which families and educators make great partners.

For some children, learning to read is a challenge—and both family support and teacher expertise are all the more important. Two decades ago, innovators in Mississippi wanted to ensure that all teachers had that expertise. They developed trainings, improved instructional materials, sent coaches into classrooms, and engaged teacher preparation programs.* Now, as fourth-grade reading achievement has soared in Mississippi, they are making what they’ve learned available for free to all through Reading Universe (which the AFT is proud to sponsor).

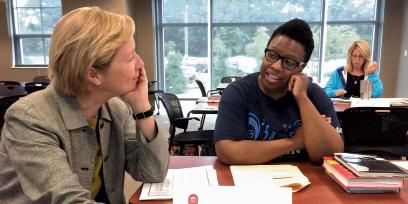

Here, Erika Bryant, a first-grade teacher in Jackson, Mississippi, and Kelly Butler, a senior advisor for Reading Universe, share highlights of Mississippi’s transformation—and offer tips on how families can advocate for better reading instruction and supports in their communities.

–EDITORS

ERIKA BRYANT: I am going into my 26th year of teaching, with the last 24 years in the Jackson Public Schools. I started off with an undergraduate degree in communicative disorders, but decided I liked being in the classroom better. So, I earned a Master of Arts degree in teaching. I’ve taught kindergarten and grades one, four, and five—here in Jackson, I’ve taught at Lake Elementary and Pecan Park Elementary, both of which I attended as a child—and have truly enjoyed it. Being a good teacher is a calling for me.

KELLY BUTLER: That’s wonderful! My teaching career began after I graduated with a degree in special education from the University of Alabama. I’ve taught at public schools in Greenwich, Connecticut, one of the most privileged areas in the country, and in Holmes County, Mississippi, which is one of the least privileged. I know that every kid deserves a great education—and it’s possible if you put the right resources and the right people in the right place.

For the last 20 years, I’ve been with the Barksdale Reading Institute (BRI) in Mississippi, and as BRI sunsetted in June 2023, I’ve recently transitioned to being a senior advisor for Reading Universe, a project initiated by BRI back in 2003. We’re taking everything we learned from working with teachers across Mississippi and making sure educators and families everywhere have what they need to ensure their children become confident readers.

ERIKA: When I came to Jackson, I was fortunate to teach in a school with a Barksdale coach, which was so vital for me. Seeing my coach work with the children, I developed as a teacher quickly. And Barksdale gave us amazing materials—our classrooms were full of books.

KELLY: I’m so glad you were in a Barksdale school. At BRI, we spent years developing our literacy model by working with teachers across hundreds of schools. We created demonstration sites to refine our approach and trained administrators so they could support excellent instruction. So, when Mississippi passed the Literacy-Based Promotion Act in 2013, we had a strong model ready to go to scale throughout the whole state, with high-quality coaching, materials, and training. At the governor’s request, we loaned two senior staff members to the Mississippi Department of Education (MDE) to help roll out the changes and supports detailed in the legislation. BRI had introduced a professional development program, the Foundations of LETRS, in 2010 to the educator preparation faculty, and so LETRS† is what we recommended for state professional development when the law passed. We also helped draft position descriptions for the literacy coaches.

ERIKA: I took LETRS training a while ago. It helped me better understand the roles of phonological awareness (or hearing the sounds in words) and writing. And, it built on the knowledge I initially developed in college about communicative disorders. For my colleagues who didn’t have that foundation—and who hadn’t worked at a Barksdale school—LETRS taught the science behind reading instruction. It really is helpful, especially for teaching K–3.

KELLY: The state began offering LETRS in 2014, so you must have been among the first teachers to receive it. Within about the first 18 months, MDE had trained close to 15,000 K–3 teachers. This was thanks to the funding allocated with that 2013 law. From the beginning, BRI has worked to improve teacher preparation for early literacy instruction. Following the 2013 law, BRI petitioned the commissioner of higher education to review what the programs were doing, given that the state was now appropriating $15 million a year to retrain teachers. This led to BRI’s development of a professional growth model for early literacy faculty to train them in the science of reading.

ERIKA: We lose new teachers because they don’t know the basics and don’t feel supported. Everyone wants us to be personal with the children—to recognize their strengths and weaknesses and to support them—so someone needs to be personal with us. This is especially true for new teachers; administrators and more seasoned teachers should be in their classrooms helping. I enjoy mentoring my new colleagues, and I learn from them too. They have shown me how to use the latest instructional technology.

All teachers need to be supported, whether that’s through better teacher preparation or coaching in the classroom—or both—so we can become the quality teachers that we are expected to be. Without that support, many of us are just wading through a whole lot of water, but we’re not getting anywhere.

When I was teaching fourth and fifth grades, I saw how critical it is to lay the foundation for reading in kindergarten and first grade. In fourth grade, the curriculum does not allow the teacher time to reteach foundational skills.

KELLY: You’re absolutely right— and we need to do more about reading challenges in upper elementary and middle grades. Prior to BRI’s sunsetting, we had begun to work with MDE to design a similar literacy model for the middle grades as we had done for K–3. Another legacy project of BRI is the creation of a new statewide reading clinic to focus initially on fourth through eighth grades. The clinic’s new metric will be the eighth-grade reading scores on NAEP (the National Assessment of Educational Progress).

The Mississippi law requires retaining children who don’t pass the third-grade reading test; it was instituted to ensure that students have sufficient foundational skills by the end of third grade because the curriculum shifts as students enter fourth grade, when they are expected to be able to learn from their reading. We worried that the retention component of the law would become the burden of nine-year-olds; however, with strong MDE leadership, the implementation focused on coaching and training for the adults—prevention, not retention. But even if a child is retained, the emphasis is on delivering purposeful interventions, targeted to address the gaps. A recent study showed that students who just barely failed the test, were retained in third grade, and received help are doing better in sixth grade than students who just barely passed.‡

As much as we were worried about this aspect of the 2013 law, in hindsight, the law was a wake-up call for teachers and school leaders. And no doubt, it was a necessary boost to bring the Barksdale model to scale throughout Mississippi. It was a game changer. Blanketing the state with training, support, and coaching gave us the traction we needed.

ERIKA: Standardized testing is stressful for all our kids, but it does give us a clear view of their growth. And it also shows the weaknesses of the lower grades. We put so much emphasis on our tested grades, starting in grade three, so there’s less attention on K–2. In Mississippi, kindergarten is not required, so my first-graders range from children who have attended preschool and kindergarten to children who have never been inside a school. I don’t think the third-grade test is misused. I think it’s a qualifier that brings appropriate attention to the earlier grades. I don’t agree with teaching to the test, but I teach the skills and know my kids will be able to perform on the test.

And while I think the testing helps, what really matters is family involvement. Being a first-grade teacher, one of the first things that I tell my kids’ parents and caregivers is, “You’re your child’s first teacher.” Literacy starts at home. I encourage families—and they know that I care about their children. I let them know that I miss their babies when they’re not at school. And, by sending home tips in children’s backpacks and hosting community nights, I share ways that families can extend what we’re doing in the classroom. For example, I ask parents and caregivers to talk to their children, to ask them about school, to sing and play word games with their children, to read to their children, and to have their children read to them. That’s especially important in the summer, when children tend to forget some skills. I encourage a lot of play during the summer and also some work practicing reading skills.

KELLY: I agree—parents are their children’s first teachers. Once children start school, families and teachers need to be equal partners. That’s what we’re trying to support with Reading Universe. Although we’re still developing the site, readinguniverse.org, we’ll be adding resources to help foster partnerships between families and educators. For example, we’re developing a series of questions that parents and teachers could ask each other to really get to know each child and best support their reading.

As parents and caregivers learn more about how children learn to read, they can also become advocates for better instructional materials and supports, including coaching for teachers and administrators. Reading Universe will give families everything they need to show their local school board members and their elected representatives what excellent reading instruction looks like—and to demand that their children’s teachers get the resources and training they deserve and want. We’re launching the website with resources for K–1, but ultimately, Reading Universe will cover preK–6.

I have enormous gratitude for teachers and appreciation for what they are asked to do day in and day out. Teachers are the bedrock of our culture. Every other profession must come through the hands of a teacher, so we owe it to this profession to provide as much support as we can.

ERIKA: Teachers do deserve support—and that’s a great reason to belong to the AFT. I’m glad that the AFT is contributing to Reading Universe; that’s yet another way my union is supporting teachers’ expertise. I’ve been a professional development presenter through my union for the past 12 years, and I enjoy this extra work. My first love is teaching children, but my second love is encouraging those around me to remain in education because our children deserve teachers who love to teach.

* To learn more about Mississippi’s transformation, see The Reading Revolution. (return to article)

† For details on LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling), see “Creating Confident Readers” in the Spring 2023 issue of American Educator. (return to article)

‡ To read the study, visit go.aft.org/kvp. (return to article)

[photos: Courtesy of Erika Bryant and Kelly Butler]