As the articles by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt and by Eric H. Holder, Jr., show, our democracy has been in decline for many years. To conclude this package on saving our democracy on a hopeful note, we turn to our youth. Their activism—especially for the Black Lives Matter movement—is inspiring: it should be supported, not squelched.

Free speech is the cornerstone of a high-functioning democracy. But all too often, speech that challenges those in power is ignored. When voices are not heard, they must become louder. And when they unify in mass protests, those voices strengthen our democracy. We are proud of the young people who are crying out to create a better, more just America that rejects its anti-Blackness and shares its opportunities. And we are proud of the educators who have helped those youth develop their understanding of social justice.

In support of young activists and the educators engaged with them, we offer excerpts from two new books: Campus Uprisings: How Student Activists and Collegiate Leaders Resist Racism and Create Hope, edited by Ty-Ron M. O. Douglas, Kmt G. Shockley, and Ivory A. Toldson, and Dare to Speak: Defending Free Speech for All, by Suzanne Nossel. Each offers thoughtful perspectives on how young people and their educational communities can preserve free speech while building a better society through protest. Both books are written with higher education in mind, and both have ideas that can be adapted to elementary and secondary schools, as well.

While both excerpts offer examples of students addressing racism, Campus Uprisings does so in a forthright manner that may be difficult for some readers. Describing racist incidents in which the N-word is used, these Black authors choose to use the word in full. The question of how to handle such language is a difficult one: we respect the authors’ choice to convey the full horror of the racist act, and we are also concerned about how it may affect our Black readers. After consulting with colleagues, we concluded that in this case, confronting the harsh reality of racism is part of the way forward. Please help us reflect on our practices by sharing your thoughts on this specific question, or on our broader efforts to reckon with racial injustice, by emailing us at ae@aft.org.

We are also committed to listening to students. We begin this salute to protest by highlighting findings from a recent poll of college students on free speech. If your students’ views on exercising their right to free speech are not being equitably voiced and heard, consider using this poll to begin a dialogue—or possibly create your own survey—and find out more about your students and the changes they aspire to make.

Helping Students Find Their Voices

Free speech is essential to our democracy, and learning communities—especially college campuses and classrooms—are key spaces for participants to explore difficult topics, to be exposed to new ideas and perspectives, and to learn to function with others in a society. Many educators cherish the ideal of truly free speech and relish opportunities to help students engage with complex issues like present-day school segregation, mass incarceration, and the treatment of refugees and immigrants—but educators also grapple with the difficulties, particularly the risk that students’ remarks will be harmful to their classmates.

Even in educational settings that aim to be inclusive, students may be discouraged from speaking up because of barriers like institutional racism and the implicit biases it fosters. For example, the tendency for educators (and other adults) to perceive Black children and teens as older, less innocent, and more disruptive than their white peers (beginning as early as preschool) leads to higher rates of suspension and expulsion, fewer mentorship and leadership opportunities, and other obstacles to preparing for college.1 Such messages are reinforced when, as we have seen repeatedly in the anti–police brutality protests following the murder of George Floyd, government responses to largely peaceful demonstrations have been mixed and have included violent, unconstitutional attempts to suppress that lawful speech.

When students who perceive that they have been silenced do make it to college, how might they feel about “appropriate” ways to make their perspectives heard? What if some students believe that safely disrupting (not merely silently protesting) a speech by a known white supremacist, for instance, is the only way they can be heard? In such situations, we hope the book excerpts that follow will foster a meaningful debate among faculty, administrators, activist students, and the broader educational community. It might at first seem necessary to punish students who disrupt events, but more productive options may emerge through dialogue.

In setting the stage for such conversations, faculty and administrators may want to consider the potential for causing real harm in asking members of marginalized social groups, such as the children of Central American immigrants or students who identify as LGBTQ, to engage intellectually with peers who believe they are inferior, sinful, or otherwise not worthy of equal rights and opportunities.2 These are tensions that educators often feel acutely as they strive to make their learning spaces welcoming to everyone while also providing opportunities for meaningful learning.

Hearing Our Students’ Words, Silences, and Actions

A recent Gallup/Knight Foundation survey of more than 3,000 full-time college students offers some insights into the ways students perceive freedom of speech to operate on campus—and emphasizes some of the challenges involved. (Download the report for free here.)

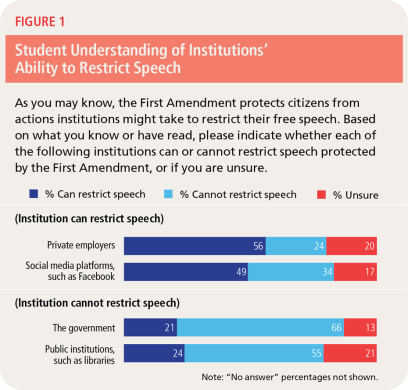

While 96 percent of students said that freedom of expression was very or extremely important (a dominant majority that persists across racial and gender demographics), many students had an incomplete understanding of what kinds of speech are actually protected and where (see Figure 1).3

Students are broadly aware that the exercise of freedom of speech occurs within larger social contexts. Among all students surveyed, 91 percent believed that it was very or extremely important that society be inclusive and welcoming to diverse groups of people. But students also recognized that practicing free speech and valuing diversity and inclusion might sometimes conflict. Although 24 to 29 percent of men, women, Democrats, independents, Republicans, and white students perceived such conflicts as frequent, 40 percent of Black students saw such conflicts as frequent.

These results show that there are many opportunities to engage students as they too grapple with what the legal and ethical limits of free expression—and their rights and responsibilities—might be.

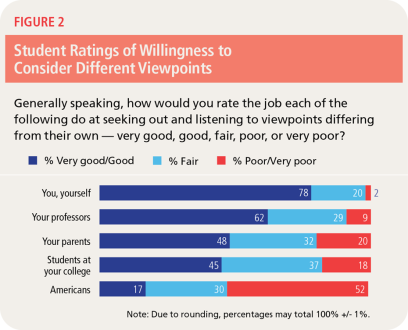

Notably, most students (62 percent) felt their professors were willing to consider other points of view, a sign that many faculty are doing a good job of listening and making sure students feel heard. Students saw themselves as doing an even better job, but they had a much lower opinion of their peers and of Americans in general (see Figure 2).4 These gaps suggest that students are not communicating with each other as clearly as they think!

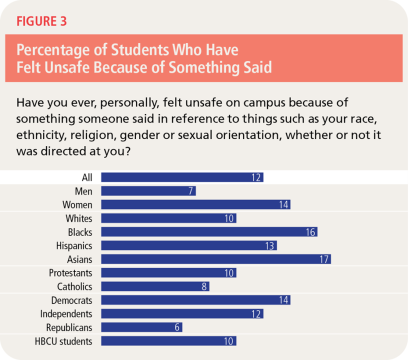

Digging into the implications of free speech sheds some more light on these disparities. Over and over, the poll data show that female students and students of color feel less safe on campus than their peers. Only 60 percent of Black students agreed that “the First Amendment protects people like me” (compared with 94 percent of white students). And 38 percent of all students reported feeling uncomfortable because of speech related to their race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexual orientation—even if those comments weren’t directed at them—including 41 percent of female students, 41 percent of Black students, and 44 percent of Asian students. Significantly, one in eight students reported feeling unsafe because of speech, with female students twice as likely to feel unsafe as male students and Black and Asian students much more likely than white students (see Figure 3).5

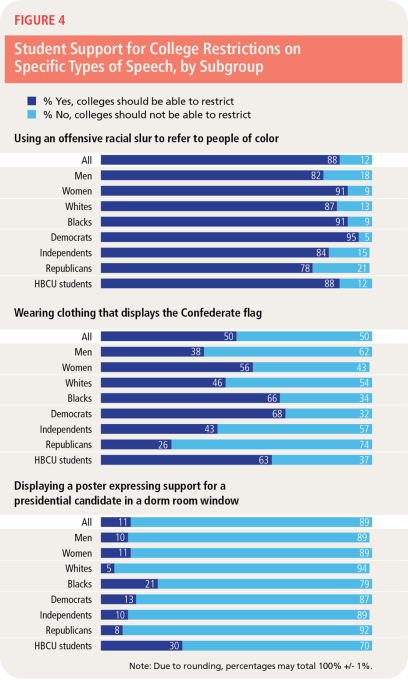

Among all students, there was broader consensus on what kinds of speech schools should restrict. While 88 percent of all students believed colleges should be able to bar the use of racial slurs and half favor restricting clothing with the Confederate flag, only 11 percent believed colleges should be able to prevent students from hanging posters endorsing political candidates in their dorm windows (see Figure 4).6

This is the heart of the issue, and it brings with it an invitation for educators to reflect: How can we help students understand the value of freedom of expression while also helping them to exercise that freedom responsibly and respectfully? How can we balance our desire to help all students to feel safe expressing themselves in our classrooms with our responsibility to make sure all students feel safe, period?

These are challenges those who work in education spaces need to think through, particularly before enacting policies, deciding punishments, or planning class discussions on difficult topics. And students should be involved in those conversations and decisions. As the survey results show, while students may have a lot to learn about free speech, they also have a lot to share.

–Editors

Endnotes

1. P. A. Goff et al., “The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106, no. 4 (2014): 526-45; R. Epstein, J.J. Blake, and T. González, Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood (Washington, DC: Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2017).

2. N.O.A. Kwate and M.S. Goodman, “Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Effects of Racism on Mental Health among Residents of Black Neighborhoods in New York City,” American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 4 (2015): 711-8; B. Ghafoori et al., “Global Perspectives on the Trauma of Hate-Based Violence: An International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Briefing Paper,” International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 2019.

3. The First Amendment on Campus 2020 Report: College Students’ Views of Free Expression (Washington, DC: Knight-Gallup, 2020), 8, fig 4.

4. The First Amendment on Campus 2020 Report, 12, fig. 8.

5. The First Amendment on Campus 2020 Report, 20, fig. 17.

6. The First Amendment on Campus 2020 Report, 26, fig. 22.

[Illustration by Lucy Naland, photos: Getty Images]