The COVID-19 pandemic has shined a light on long-festering problems in our health system. It is not a pretty picture: from racial and ethnic health disparities;1 to the low wages and minimal benefits of the long-term care and home-care workforce (who often have to work more than one job to get by and may have no sick leave or healthcare coverage);2 to the maldistribution of our health workforce, especially in rural areas;3 to the hyperdependence of hospitals on elective procedures for their financial sustainability;4 to staff burnout;5 to racism in our workplaces;6 to poor crisis preparedness and the ensuing lack of personal protective equipment in hospitals;7 and ultimately to the tragic shortages of critical care staff as hospitalizations surged around the country.8

For nurses, and healthcare workers more generally, the lived experience of these factors long predated the pandemic, but COVID-19 (exacerbated by the Trump administration’s inadequate response) is forcing us to rethink assumptions about what causes these problems and how best to address them. These problems are systemic and merit bolder changes than generally have been considered up until now.

“Burnout” Hides Systemic Problems

As with so much in our profit-driven healthcare industry, the interrelated problems of nurses’ working conditions, high rates of burnout, and turnover have been largely analyzed not in terms of impact on providers, patients, or safety, but in terms of hospital costs. One pre-pandemic study showed that 54 percent of critical care nurses intended to leave their job within the next year.9 Other studies found that the turnover rate among hospital bedside nurses had climbed to 17 percent in 201910 and that each nurse who left the hospital was estimated to cost up to $64,000 to replace.11 The human costs—including dreams of long nursing careers abandoned, chronic conditions developed as a result of stress, and patient care compromised—are incalculable. During the pandemic, a combination of the high numbers of nurses needed and the high staff attrition (due to illness, family demands, and unbearable conditions) has driven these human and economic costs up further.12

The study of burnout has made important contributions, offering administrators—if they decide to address burnout—clear pathways for improving working conditions. Research has identified workload, work schedules, staffing ratios, and time spent on administrative tasks and charting as causal factors.13 Studies have also shown that in addition to causing nurse stress and attrition, burnout negatively affects patient outcomes.14 Research on the solutions to burnout tends to focus on ways to increase nurse retention. These include, for example, new nurse graduate residency (as transition to practice) programs;15 the Magnet Recognition Program, which recognizes hospitals that have positive nurse work environments;16 staff satisfaction and engagement questionnaires that are used by employers to anticipate problems with motivation, absenteeism, and turnover;17 and a plethora of psychology-based models of organizational engagement, such as PROPEL, that seek to build interpersonal skills in teams to manage stress and demoralization.18

All of these approaches have had moderate success in increasing retention, but they have also been shown to be insufficient to stem the bleeding. Fundamentally, they are not cures—they are bandages applied at the individual and organizational levels, and they are hiding the disease being caused by a system that puts profits ahead of patients and providers. Increasingly, the concept of burnout is being challenged, with some going so far as to suggest it is victim blaming, placing responsibility on those experiencing burnout for being insufficiently resourceful or resilient to “withstand the work environment.”19 But if the real problem does not reside at the individual or organizational level, it cannot be addressed by increasing individual resilience or even by making significant organizational changes such as increased pay and staffing. As scholars at the forefront of challenging burnout starkly framed the issue, “It is absurd to believe that yoga will solve the problems of treating a cancer patient with a declined preauthorization for chemotherapy.”20

Defining Moral Injury

An alternative frame that is gaining traction is moral injury. The concept was originally studied in the context of members of the military returning from combat. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) defines moral injury as “the distressing psychological, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure” to three types of events: (1) when someone does something that goes against their beliefs (commission of an act); (2) when someone fails to do something in line with their beliefs (omission); and (3) when someone experiences betrayal from leadership, others in positions of power, or peers.21 The VHA further affirms that moral injury can occur in response to witnessing behaviors that conflict with an individual’s values. The injury itself occurs when the individual perceives that a line has been crossed, and as a result they experience some combination of guilt, shame, disgust, and/or anger. The hallmarks of moral injury have been the inability to forgive oneself, self-destructive behaviors, and demoralization.

Not surprisingly, the concept caught on quickly among healthcare workers. The first definition, published in 1984, referred to situations in which a nurse “knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.”22 Key to this definition were the ideas that there is moral certainty of the right course of action and that there is a system-level constraint that prevents the nurse from being able to act accordingly.23 This definition has expanded over time to include situations that give rise to distress but that are not necessarily cases of certainty and constraint, such as when there is moral uncertainty or conflict about what is moral.24

Regardless of the narrower versus broader definition, experts agree that moral stressors vary in severity, with the least severe, in theory, being more prevalent and the most harmful events less frequent.25 In recognition of this variability, moral injury is often used to indicate one type of trauma, while moral distress is often used to indicate real but lesser suffering. (Both terms are used throughout this article. As with other stressors, what is distressing to one person may be injurious to another; also, moral distress that is ignored may become moral injury.)

Applying the Concept of Moral Injury

As the concept of moral injury has gained popularity, it has been used in practice in different ways—both within the field of healthcare and in other fields. Some identify it as one cause of burnout and therefore continue to focus on managing symptoms in order to increase staff retention and build resiliency.26 Others are trying to use the concept of moral injury to shift attention from individuals’ responses to a system to the constraints systems impose on individuals.27 Identification of the system-level factors that are the causes of moral distress and injury requires focusing on system-level solutions, some of which may not be viewed as modifiable by managers.

In healthcare, the umbrella system-level factor most often identified as a cause of moral injury is its for-profit underpinnings. Health systems may discourage caring relationships by limiting time with patients and focusing health workers’ attention on administrative tasks, such as electronic health records and paperwork for insurance companies. In that context, moral injury occurs when nurses, and other healthcare workers who are committed to compassionate care, confront a system that cares primarily about profit.28

This is a particularly powerful notion for nursing since nursing is at its core about human caring: nurses aspire to holistic care provided through authentic relationships with patients.29 The experience of an immoral event, whether distressing or traumatic, presents not just a personal dilemma but a professional one as well. The professional identity of a healthcare provider as a caregiver, socialized during professional education and in the early years of practice, provides the backdrop that gives meaning to specific events. Fortunately, that professional identity, while possibly exacerbating stress and trauma, also serves as a platform for long-term collective action that achieves change. The Code of Ethics by the American Nurses Association (ANA),30 for example, offers a strong road map for responding to immoral situations, even if nurses are not always empowered to act on its principles. ANA itself recognized this and has launched an educational project around moral distress.31 Most of its work focuses on defining the concept of moral distress and generally identifying the prevalence of the problem—it has, thus far, left the system-level causes of distress and injury somewhat opaque.

Giving Voice to Moral Injury

How can we give voice to nurses’ own experiences of moral injury in different settings and link these systemic conflicts to specific policy and regulatory changes? In particular, it would be helpful to juxtapose elements of nurses’ professional identity (as expressed in ANA’s Code of Ethics or other theoretical documents) with the potential system-level barriers to fulfilling that identity. These pain points need clarification and amplification so that frontline nurses can understand the nature of the conflict and position themselves to lead policy change.

Some of these pain points are more visible and, therefore, more discussed than others. Take the problem of a nurse who is a single mom and fears reporting a safety problem because of potential reprisal from an attending physician who has the power to move her to a night shift. The ANA code speaks to this issue in the section on “Protection of Patient Health and Safety by Acting on Questionable Practice,”32 and some hospitals have instituted systems with whistleblower protections to encourage people to speak out. This is a well-known problem, and while it persists, there are well-known system-level solutions for frontline nurses.

There are also many issues causing moral distress that are well known but rarely discussed among nurses, likely because the solution requires challenging some of the most basic tenets of for-profit organizations. These situations are particularly common for nurses in leadership roles. Here are some hypothetical cases:

- A chief nursing officer (CNO) is under pressure from the chief financial officer to reduce nursing costs in a hospital. Aware that many states and the public are starting to track nurse-to-patient ratios, the CNO opts to reduce nursing assistive personnel. She experiences moral distress because her action not only leaves people unemployed but also creates more work for the nurse staff and could endanger patients.

- A CNO in a nursing home with high nurse turnover is desperate to hire more nurses quickly. The pressure to cover vacancies in specialty areas leads him to contract with an international nurse staffing agency, even though the agency is known for underpaying international nurses and using high contract-breach fees to prevent them from quitting. He is distressed because he knows that the international nurses will be assigned less favorable shifts and will receive less pay than their US counterparts.

- A member of the state board on nursing fears speaking out about the low quality of for-profit nursing schools in the state because state legislators, who are lobbied and funded by the for-profit education industry, would likely reduce the power of the board’s oversight in retaliation. She experiences moral distress because she fears that her inaction could lead to hundreds of new nurse graduates who will fail their licensure tests, delay entry into the profession, and face difficulty repaying their student loans.

- A nurse working in utilization management for an insurance company is troubled by the protocols that reject payment for certain high-cost drugs, but she knows if she is too lenient with the approval process she could lose her job. She experiences moral distress knowing that patients’ health may be harmed by these denials.

- A nurse in an assisted nursing facility is aware that some of the therapeutic services and drugs provided to residents are not necessary. While there are whistleblower protections in his organization, no one has ever used them. He fears that if he reports the overuse, he will face reprisals from his managers—but the longer he stays silent, the more distressed he feels.

These are some of the many common stressors that can cause moral injury, not just for the individuals committing the particular act, or omitting an action, but also for those who are witnessing the practices. Even once the pandemic is over, these stressors will remain until we find the collective will to reimagine our healthcare system. One of our nation’s most severe causes of moral injury—structural racism—will also remain until we reckon with the very foundations of our social, economic, and political structures (for an introduction to healthcare’s role in that reckoning, see the sidebar to the right.)

Addressing the Causes of Moral Injury

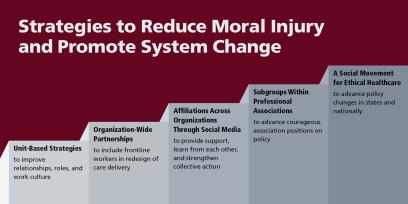

The challenge is how to increase the conversation about these “untouchable” topics and how to address them. As shown in the figure below, there are many levels of potential strategies, none of which are mutually exclusive. For healthcare unions, all of these levels present opportunities to help alleviate moral injury—especially as union membership grows throughout the healthcare workforce.

The strategies begin at the unit level and involve improving participation and team dynamics. They advance to organization-wide labor-management partnerships that give frontline staff a voice in system redesign within healthcare organizations. Then there is the option to use social media to create affinity groups that encourage the sharing of stories and organizing platforms across organizations. Next, there are subgroups of nurses that can create campaigns within professional associations to advocate for more courageous positions based on professional ethics. Lastly, a macro-level strategy is to build statewide and nationwide social movements that are independent of single professions or political parties and can push for specific policy reforms.

Unit-Based Strategies

The first strategy is to give frontline staff a greater voice in unit-level decisions and to create a culture of participation and respect. Approaches such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s advancement of unit-based teams that work on continuous quality improvement lay the groundwork for frontline workers to have greater input into the redesign of care delivery.33 In the context of COVID-19, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement stresses a number of leadership strategies. By taking these actions, leaders can help prevent and mitigate the effects of moral injury:

- Meet the needs of the health workforce during the crisis by providing PPE (personal protective equipment) for everyone at risk (e.g., including hospital laundry staff), food in break rooms, childcare resources, transportation support, mental health services, etc. (Long term, this also means, at a minimum, living wages, health insurance, and paid leave. Although these may be organization-level decisions, unit-level leaders have a responsibility to speak up for their teams.)

- Communicate regularly and honestly, listening to workers’ concerns (including through formalized listening sessions) and asking questions such as What went well today? and What can we build on?

- Normalize and encourage help-seeking behavior as a sign of strength and part of a shared value of prioritizing wellness.

- Acknowledge grief, while also offering hope and a path forward.34

This first level of actions is critical, but it is limited in that it focuses primarily on areas in which staff (including unit leadership) action can affect change. Many of the causes of moral injury cannot be resolved at the unit level.

Organization-Wide Partnerships

A step up from unit-level approaches are institution-wide partnerships on a broad range of issues, which may include unit-based quality improvement, staffing ratios, new hires, wages and benefits, and workforce development programs, as well as more general questions of revenue and resource allocation in the general budget. These are areas that have traditionally been considered off limits to frontline workers. But, especially in hospitals with unionized staff, these issues may be effectively addressed through ongoing dialogue that centers workers’ experiences and ideas. This approach, which is sometimes formalized as a labor-management partnership (LMP), uses a variety of techniques to engage workers in the diagnosis and resolution of organization-level problems.35

A number of LMPs have noteworthy accomplishments to date. Kaiser Permanente’s LMP has a campaign called Free to Speak that includes a set of tools intended to make everyone feel it is safe to speak up. The tools, Kaiser writes, “underscore not just the right to speak up but the responsibility of workers, managers and caregivers to do so.”36 Maimonides Medical Center uses Study Action Teams, an interdisciplinary group of six to eight frontline workers, managers, and technical staff who are assigned the task of studying a problem and proposing organizational changes. Their aim is to identify disruptive changes that can contribute to broader transformations.37

The role of unions in facilitating labor-management partnerships is well documented, although not all unions view such arrangements as advantageous.38 Certainly, some union leaders (or some representatives on the LMPs) are less connected to their members’ needs; other unions may view LMPs as getting too close to management. Contexts vary, and sometimes partnerships are not feasible, but periodically considering LMPs is worthwhile because much can be accomplished for patients and providers when genuine collaboration is possible. For local and national unions, detailed study of the potential advantages and pitfalls of LMPs remains an important area of work in and of itself.39

Affiliations Across Organizations Through Social Media

The use of social media provides a third strategy for mobilizing action that can address moral injury. With only 20 percent of healthcare workers unionized, and most of those concentrated in hospitals, many nurses do not know where to turn when experiencing stressors—especially when raising their concerns related to their colleagues’ or managers’ ethics. Platforms like Twitter have enabled individual nurses to connect with like-minded health professionals across the country, regardless of their institutional affiliations, to discuss problems and solutions. (Many nurses have created profiles that protect their identities and, thus, their jobs, particularly if they work at hospitals with gag orders.) For more in-depth problem solving, closed groups on platforms like Facebook have facilitated dialogue in ways that were not previously possible, both within and across workplaces. That dialogue can lead to substantive discussions, exchanges of strategies being used in different units or facilities, and the development of action plans.

While social media is helpful when there is no labor union, it is also used by labor leaders and members—especially when in-person meetings are not possible. Ideally, union members and leaders will be active on social media to facilitate greater participation within the union, to expand their reach to potential new members, to learn more about their communities’ needs, and to share their values and goals with their communities. As the pandemic has shown, union leaders—and all healthcare providers—are also important community leaders who are sharing information about the benefits of masks and social distancing as well as the safety of vaccines.

Subgroups Within Professional Associations

Building on the organizing potential of social media, a fourth strategy is to encourage professional associations to adopt more courageous stances. Professional associations (as distinct from unions of professionals like the AFT) generally regulate and set standards for a profession. Across professions, even outside healthcare, such organizations are notoriously cautious in the positions they assume and the battles they choose to fight. This is a function of attempting to encompass the full profession, representing a wide range of views and interests. However, these associations occupy an important role in educating policymakers, and they often have a seat at the table in policy negotiations. As such, it is important to strengthen their understanding of and commitment to frontline nurses’ and other healthcare workers’ experiences. For example, when moral injury results from problems like the relative paucity of people of color in higher-level and leadership roles throughout the healthcare field (from professors to surgeons to CEOs to lobbyists), that is a profession-wide concern that demands profession-wide action.

In the era of social media and Zoom, members of professional associations can now essentially self-convene, and subgroups can set their own agendas. Such was the case after ANA decided in 2019 to limit its political action committee to races in the US Congress, thereby remaining neutral on the presidential election.40 Many nurses viewed the Trump administration’s lack of leadership in the COVID-19 response as a matter of professional ethics and were outraged when nurse leaders participated in White House photo opportunities—especially because they were not wearing masks.41 But some saw ANA leadership’s actions as attempts to capitalize on opportunities to convey the impact of COVID-19 on nurses and the need for nurses to be involved in developing policies related to reopening businesses and schools.42 The resulting surge of protest by nurses across the country via social media calling for ANA to take a position against the Trump administration suggests that it is easier than it used to be to challenge professional leadership.43 No matter whether one agrees with ANA’s stance or with the protestors, it is heartening to see that individuals can create their own leadership roles and that grassroots nurses can pressure organizations to change.

A Social Movement for Ethical Healthcare

The fifth and most macro-level strategy involves building a social movement around healthcare ethics. Other nations have universal access to healthcare complemented by strong public health movements that include a broad range of health workers, as well as activists in the general population. This combination is how many countries—especially wealthy nations—have achieved healthier populations and lower healthcare costs than the United States.44 Even countries with fewer resources, such as Brazil and Mexico, have built such movements and successfully influenced health reforms in their respective countries.45 In the United States, similar movements are growing around the recognition of healthcare as a human right—a position long championed by civil rights activists and receiving increased attention with the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and the multiple attempts to repeal it in the decade that followed46—and the creation of new payment models that prioritize health.* The leaders of these movements around the world see themselves as ideologically committed to a “health for all” platform but are careful to avoid being profession-specific or partisan in their affiliation. They demand a seat at the table, alongside other more traditional stakeholder groups, and while they are viewed as ideologically driven, they have the added legitimacy of being seen as relatively free from vested interests specific to a single profession or party.

Working toward a broader social movement that focuses on the problems engendered by the commercial orientation and profit-driven nature of our healthcare system is no small undertaking, but it is probably the only way to alter the most significant structural causes of moral injury. Labor unions, nongovernmental groups, academic groups, and professional associations could play an important role in facilitating such a movement.

Managing moral distress, as well as other forms of stress, and creating joy in nursing work are noble goals, and yet they are insufficient. Individual- and organizational-level policies and programs are essential, but they do not necessarily address all the root causes of moral injury. Nurses, along with other healthcare providers, need to elevate the discussion of moral injury to a system-level conversation about solutions. Until the major sources of moral injury are addressed across many different practice settings, a large segment of the nurse workforce will continue seeking to reduce their work hours and even leaving the profession as soon as they can.

The range of strategies that can be used to address moral injury includes partnerships with frontline workers at the unit level and across the healthcare organization, using social media to enhance interaction and organizing among nurses outside of their workplaces, increasing the grassroots pressure on professional organizations to take bolder positions, and building a cross-profession social movement to advance health policy changes nationally. These strategies are mutually supportive and can be used in different ways by different players within the nursing profession as we work together to build a healthcare system in the United States that values health and the essential work of caring for one another.

Patricia Pittman, PhD, FAAN, is a professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management in the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, with a secondary appointment in the School of Nursing. She is also the director of the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity and is the principal investigator for two federally supported health workforce research centers.

*See, for example, “COVID-19: From Public Health Crisis to Healthcare Evolution” in the inaugural issue of AFT Health Care. (return to article)

Endnotes

1. M. Chowkwanyun and A. Reed, “Racial Disparities and COVID-19—Caution and Context,” New England Journal of Medicine 383 (July 16, 2020): 201–203.

2. K. Scales and M. Lepore, “Always Essential: Valuing Direct Care Workers in Long-Term Care,” Public Policy & Aging Report 30, no. 4 (2020): 173–77.

3. Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity, “State Hospital Workforce Deficit Estimator,” gwhwi.org/estimator.html; and WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, “Supply and Distribution of the Primary Care Workforce in Rural America,” Policy Brief No. 167, University of Washington, June 2020, depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/06/RHRC_PB167_Larson.pdf.

4. J. Garber, “A Silver-Lining to COVID-19: Fewer Low-Value Elective Procedures,” Lown Institute, April 20, 2020, lowninstitute.org/a-silver-lining-to-covid-19-fewer-low-value-elective-procedures.

5. N. Talaee et al., “Stress and Burnout in Health Care Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic: Validation of a Questionnaire,” Journal of Public Health (Berlin) (2020), ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7275852.

6. A. Garran and B. Rasmussen, “How Should Organizations Respond to Racism Against Health Care Workers?,” AMA Journal of Ethics 21, no. 6 (2019): E499–E504.

7. T. Rebmann, A. Vassallo, and J. Holdsworth, “Availability of Personal Protective Equipment and Infection Prevention Supplies During the First Month of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Study by the APIC COVID-19 Task Force,” American Journal of Infection Control (2020), ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553(20)30814-2/fulltext.

8. Fitzhugh Mullan Institute, “State Hospital Workforce”; O. Goldhill, “‘People Are Going to Die’: Hospitals in Half the States Are Facing a Massive Staffing Shortage as Covid-19 Surges,” Stat News, November 19, 2020, statnews.com/2020/11/19/covid19-hospitals-in-half-the-states-facing-massive-staffing-shortage.

9. B. Ulrich et al., “Critical Care Nurse Work Environments 2018: Findings and Implications,” Critical Care Nurse 39, no. 2 (April 1, 2019): 67–84.

10. F. Shaffer and L. Curtin, “Nurse Turnover: Understand It, Reduce It,” American Nurse Journal, August 10, 2020, myamericannurse.com/nurse-turnover-understand-it-reduce-it.

11. Lewin Group, Evaluation of the Robert Wood Johnson Wisdom at Work (Falls Church, VA: Lewin Group, 2009), rwjf.org/en/library/research/2009/01/evaluation-of-the-robert-wood-johnson-wisdom-at-work.html.

12. J. George, “Bidding War for Nurses; Cutting Quarantine Time; ‘Out of Control Fire,’” MedPage Today, November 25, 2020, medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/89885.

13. National Academy of Medicine, Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2019).

14. D. Vahey et al., “Nurse Burnout and Patient Satisfaction,” Medical Care 42, no. 2 Suppl. (January 31, 2004): II57–II66; and L. Aiken et al., “Effects of Hospital Care Environment on Patient Morality and Nurse Outcomes,” Journal of Nursing Administration 38, no. 5 (May 2008): 223–29.

15. J. Medas et al., “Outcomes of a Comprehensive Nurse Residency Program,” Nursing Management 46, no. 11 (November 2015): 40–48.

16. C. Friese et al., “Hospitals in ‘Magnet’ Program Show Better Patient Outcomes on Mortality Measures Compared to Non-‘Magnet’ Hospitals,” Health Affairs 34, no. 6 (2015): 986–92.

17. See, for example, B. Bredimus, “Changing Culture to Drive Nurse Engagement and Superior Patient Experience,” Nurse Leader 17, no. 5 (October 1, 2019): 395–98.

18. T. Muha and M. Murphy, PROPEL to Quality Healthcare: Six Steps to Improve Patient Care, Staff Engagement, and the Bottom Line (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2018).

19. W. Dean, S. Talbot, and A. Dean, “Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout,” Federal Practitioner 36, no. 9 (September 2019): 400–402.

20. Dean, Talbot, and Dean, “Reframing Clinician Distress.”

21. S. Norman and S. Maguen, “Moral Injury,” National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veterans Affairs, www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/cooccurring/moral_injury.asp.

22. A. Jameton, Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984).

23. C. Fourie, “Who Is Experiencing What Kind of Moral Distress? Distinctions for Moving from a Narrow to a Broad Definition of Moral Distress,” AMA Journal of Ethics 19, no. 6 (2017): 578–84.

24. C. Fourie, “Moral Distress and Moral Conflict in Clinical Ethics,” Bioethics 29, no. 2 (February 2015): 91–97.

25. Racial Inequities and Moral Distress: A Supplement to Moral Stress Amongst Healthcare Workers During COVID-19; A Guide to Moral Injury (Centre of Excellence on PTSD and Phoenix Australia, August 2020), moralinjuryguide.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/racial-inequities-and-moral-distress.pdf.

26. Are Your Nurses Experiencing Moral Injury? What You Can Do to Support Your Team, white paper (Morrisville, NC: Relias, 2020).

27. Moral Injury of Healthcare, “Moral Injury of Healthcare,” fixmoralinjury.org.

28. Dean, Talbot, and Dean, “Reframing Clinician Distress.”

29. A. Lukose, “Developing a Practice Model for Watson’s Theory of Caring,” Nursing Science Quarterly 24, no. 1 (2011): 27–30.

30. American Nurses Association, “View the Code of Ethics for Nurses,” nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses.

31. See, for example, J. Batcheller, “A Nurse’s Guide to Preventing Compassion Fatigue, Moral Distress, and Burnout,” American Nurses Association, nursingworld.org/continuing-education/online-courses/a-nurses-guide-to-preventing-compassion-fatigue-moral-distress-and-burno-12b2af6c.

32. See “3.5 Protection of Patient Health and Safety by Acting on Questionable Practice,” in Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretative Statements (Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association, 2015), nursingworld.org/coe-view-only.

33. R. Resar et al., Frontline Dyad Approach to Maximize Frontline Engagement in Improvement and Minimize Resource Use (Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, March 2012).

34. IHI Multimedia Team, “How Leaders Can Promote Health Care Workforce Well-Being,” Improvement Blog, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, December 10, 2020, ihi.org/communities/blogs/how-leaders-can-promote-health-care-workforce-wellbeing.

35. “Chapter 1: The Evolution and Value of Labor-Management Partnerships,” in From the Ground Up: How Frontline Staff Can Save America’s Healthcare, ed. P. Lazes and M. Rudden (Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2020).

36. Labor Management Partnership, Kaiser Permanente, “Free to Speak,” lmpartnership.org/focus-areas/free-to-speak.

37. Lazes and Rudden, From the Ground Up.

38. Lazes and Rudden, From the Ground Up.

39. P. Pittman and E. Scully-Russ, “Workforce Planning and Development in Times of Delivery System Transformation,” Human Resources for Health 14 (2016): 56.

40. C. Myers, “ANA Adopts New Presidential Election Policy,” American Journal of Nursing 119, no. 10 (October 2019): 19–20.

41. T. Vásquez, “Nurses Association’s Refusal to Denounce Trump Angers Members,” Prism, October 12, 2020, prismreports.org/article/2020/10/12/nurses-associations-refusal-to-denounce-trump-angers-members.

42. See, for example, American Nurses Association, “ANA President Visits White House for Nurses Day Proclamation Signing Ceremony,” May 6, 2020, nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2020/ana-president-visits-white-house--for-nurses-day-proclamation-signing-ceremony.

43. See, for example, J. Berklan, “Providers Outraged After ‘Insulting’ Trump Tweet Downplays COVID-19 Dangers,” McKnight’s, October 6, 2020, mcknights.com/news/providers-outraged-after-insulting-trump-tweet-downplays-covid-19-dangers; J. Ensign, “Past Presidents of the ANA Endorse Biden-Harris,” Medical Margins: On Humanizing Health Care (blog), September 25, 2020, josephineensign.com/2020/09/25/past-presidents-of-the-ana-endorse-biden-harris; and “We Are Nurses, America’s Most Trusted Profession. And We Support Biden,” Newsweek, October 2, 2020, newsweek.com/we-are-nurses-americas-most-trusted-profession-we-support-biden-opinion-1535962.

44. R. Tikkanen and M. Abrams, U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019: Higher Spending, Worse Outcomes? (New York: Commonwealth Fund, January 2020), commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019; and L. Tran, F. Zimmerman, and J. Fielding, “Public Health and the Economy Could Be Served by Reallocating Medical Expenditures to Social Programs,” Social Science and Medicine 3 (December 2017): 185–191.

45. R. Abrantas Pêgo and C. Almeida, “Theory and Practice in Health Systems Reform in Brazil and Mexico,” Cad. Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro 18, no. 4 (July/August 2002): 971–989, scielo.br/pdf/csp/v18n4/10180.pdf.

46. V. Newkirk, “The Fight for Health Care Has Always Been About Civil Rights,” The Atlantic, June 27, 2017, theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/06/the-fight-for-health-care-is-really-all-about-civil-rights/531855; and J. Cohn, “The ACA, Repeal, and the Politics of Backlash,” Health Affairs Blog, March 6, 2020, healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200305.771008/full.

[Photo Credits: Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Chicago Sun-Times via AP, Tayfun Coskun / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images, Ashlee Rezin Garcia / Chicago Sun-Times via AP, Erin Clark / The Boston Globe via Getty Images, Go Nakamura / Getty Images]